Thinking least (or a lot) of death: On the toxicity of positive thinking, and the power of philosophy as therapy

I don't like talking to other patients. There was a woman the other day in the waiting room (same cancer, but not as advanced, so her outlook is statistically better than mine). We began to talk, and she said, possibly in an attempt to cheer us up, “We just got to stay positive. If you think positively, you'll beat it.”

I don't like the implicature that if you don't survive, it was by lack of positive thinking or willpower.

This woman, like many Americans, believes in positive thinking. As Barbara Ehrenreich argues in Bright-sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America (2009), positive thinking is a toxic, undermining philosophy. It says something clearly false: if only you believe it enough, you will get what you want, be it a job, your financial situation improved, your cancer gone, you can magically think all evils away. All you need is to do is to believe it.

The history of how this individualistic wish-fulfillment philosophy began is complex. It's rooted in Calvinist predestination, American individualism, self-sufficiency, and Evangelical Christianity. From a distant, stern figure, God turned into this wishing well that can fulfill your every desire. This thinking furthers capitalist interests and the normalcy that it requires: if only you save money, get a college degree, get a mortgage, marry wisely, etc etc., then a happy, long life is yours.

It's a lie, of course. Ehrenreich relentlessly exposes how positive thinking causes misery. She shows there's no evidence positive thinking can help cure cancer, and far from beneficial, “the sugar-coating of cancer can exact a dreadful cost. First, it requires the denial of understandable feelings of anger and fear, all of which must be buried under a cosmetic layer of cheer.” The financial crash of 2008 also clearly showed the limits of positive thinking: many people who dutifully saved, and dutifully studied, and took mortgages wondered: I did everything right, how did things turn out wrong anyway?

Positive thinking is a particularly harmful form of philosophical plumbing. As philosopher Mary Midgley describes it,

Plumbing and philosophy are both activities that arise because elaborate cultures like ours have, beneath their surface, a fairly complex system which is usually unnoticed, but which sometimes goes wrong. In both cases, this can have serious consequences. Each system supplies vital needs for those who live above it. Each is hard to repair when it does go wrong, because neither of them was ever consciously planned as a whole… Whether we want it or not, the way our society is organized is deeply philosophical (Midgley, 1992, p. 139).

This is why Mary Midgley says it's important to do philosophy. We'll have philosophical plumbing anyway, so it is altogether better that we are thoughtful about it. This means having some professional specialization: people who as a job scrutinize the plumbing and who can make changes (through their writing and speaking). I try to be a plumber.

So, it's important to remove positive thinking from the American (and global) philosophical plumbing. Not because we are indifferent to suffering, but precisely because we care. I think also that positive thinking underlies the post-2021 urge to normalcy: if only we act as if normal and believe it strongly enough, normal will follow (never mind the sky-high school absenteism, long-term illness and people being out of work, that long covid still has no cure etc). Positive thinking and denialism are natural allies. As Ehrenreich remarks, “we cannot levitate ourselves into that blessed condition by wishing it. We need to brace ourselves for a struggle against terrifying obstacles, both of our own making and imposed by the natural world. And the first step is to recover from the mass delusion that is positive thinking.”

Meanwhile, I try to think positively about my illness, which due to its type and advanced stage has dicey odds. So here is my positive thought: No matter what happens, I will be okay. Seneca says that we have to die at some point. Our lives are a tiny flicker in a huge vastness of space-time. So does it matter when, exactly, we die? Or he says that when you know how to die, you've liberated yourself (from slavery). Moreover, I also think that I have been extremely fortunate to become as old as I am (mid-forties is historically old, many people did not survive their infancy), and I've been able to flourish as a human being in the full sense: with loving people around me, friends and family, doing things I enjoy doing, gaining professional fulfillment in writing and teaching. Many people never get to enjoy these goods (which is saddening). These are goods I enjoyed, no matter what the future holds.

Thinking these Stoic thoughts is also positive thinking. I don't need to gain any benefit from being gravely ill. There is no higher lesson to be learned. It's totally fine to say: this just sucks. I don't need to put “cancer survivor” in my bio if I do survive (OK if others do it), if I don't want this to define me. I don't need to worry about whether I think positively enough. I can go through the treatment, eat well, enjoy things, and leave the outcome up to medicine and fate, in the assured sense that I will be fine either way.

Is Seneca self-help? We often use the term “self-help” in a derogatory sense. However, among the most profound philosophy are works that are clearly meant, at least in part or even wholly, as self-help: Marcus Aurelius's Meditations, Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy, Spinoza's Ethics.

How does philosophical self-help differ from the shallow advice to think positive thoughts you can find on the shelves in the self-help section? The difference is as follows, I think: Philosophical therapy presents a picture of the world that discloses some aspects of reality that we, in our day to day lives, don't see sufficiently. Merleau-Ponty sees philosophy as slackening of “the intentional threads which attach us to the world and thus brings them to our notice.” For example, the Buddhist concept of anatman (no-self) discloses and brings into our notice some aspects of your impermanence: you are not the same as you yesterday, as you when you were four years old, etc.

Rather than be dismissive of philosophy as therapy, we should laud it. Its ability to help us in difficult times genuinely points to one of the great values of philosophy and why we keep on doing it. We resonate with all those people in the past struggling with the very same worries we have (loss, fear, death etc) and finding sophisticated, creative ways of dealing with them by broadening our perceptions of the world and our possibilities to stand in the world.

And so, we can find some way to get to terms with death, for instance, by thinking about it as least as possible (e.g., Spinoza) and just live life to the fullest or to think about it a lot (e.g., Heidegger) and see yourself in this formidable finiteness. There are many creative ways to go.

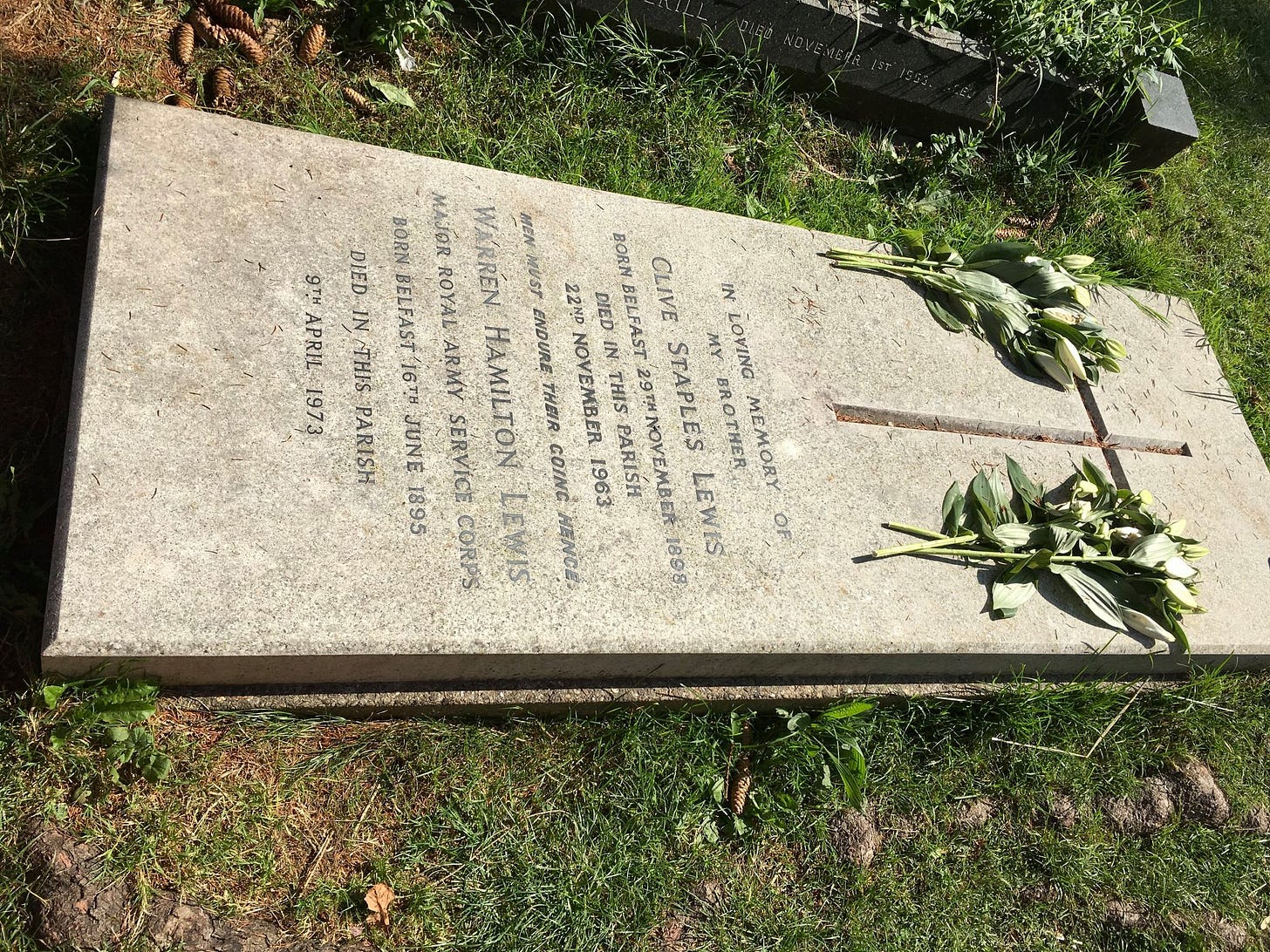

Ultimately, everyone has to face death, even if seems comfortably far in the future and you have no reason to think it's going to happen soon. It will happen eventually. CS Lewis's grave (with his brother, Warnie) has the intriguing quote from King Lear “Men must endure their going hence.” (see pictured above). We have to come to terms with it. Maybe a philosopher is not especially better fit for this task than anyone else but at least philosophy, as a practice, can give us some options to think.

First, as much as I admire your honesty and Stoicism, I hope you don't mind that I am still going to hope for a positive outcome (i.e., remission) for you.💔

Next: In terms of the "self-help" industry, years of working in bookstores convinced me that many (if not most) of the authors are clearly engaged in a cynical and malicious grift.

That said, when I commute to work on the subway, I almost always read a novel...doing so, I can't help but grudgingly admire those who use that time to read books they believe will improve their lives. Misguided or not, they are doing that BEFORE spending 8 hours (or more) making other people rich.

I make no apologies for my reading tastes, but I have to admit that I am indulging in escapism, while others are "working" before they even get to their workplaces. I'm not so arrogant to think that my way is better than theirs.

This is really lovely, Helen - thank you for sharing! I also hate the modern conception of 'positive thinking' that doesn't acknowledge or embrace tragedy and pain. I'm a cheerful person by disposition, but I've also struggled with depression and anxiety at various times in my life, and I don't experience those things as at odds. They're both reasonable ways of viewing the world; the only lie is when people claim one perspective is more "virtuous" or "authentic" than the other.