The richness of reason part II -- Fontenelle's case for STEM education for women and girls

To Kant's annoyance, Bernard le Bouvier de Fontenelle helped to pave the way for women's education in the sciences

(part of a series on Enlightenment conceptions of reason. Read part 1 on Marin Mersenne and music, here)

Kant didn't like educated women

Oh, women, why would you learn something as difficult as… geometry? Why would you fill your pretty little heads with all that Latin and Greek? Learned women exist but why? Like that mathematician, the Marquise du Châtelet…Doesn't she realize doing math makes her ugly? Women should be beautiful and shut up. All that effort belongs to the sublime, and the sublime is not for women.

These are Immanuel Kant's thoughts on the relationship between aesthetics and gender in his essay The Beautiful and the sublime (1757). Kant, like many other early moderns, was alarmed by the advances women were making in the arts and the sciences. His treatise contains deeply philosophical gems like this one:

A woman who has a head full of Greek, like Mme. Dacier, or who conducts thorough disputations about mechanics, like the Marquise du Châtelet, as well also wear a beard; for that might perhaps better express the mien of depth for which they strive.

Emilie du Châtelet was a pioneering physicist and mathematician. Though largely self-educated, and barred due to her gender from learned societies, she understood Newton's and Leibniz's calculus and introduced Newton's mechanics into the French-speaking world.

Anne Dacier ably translated the Illiad (1699) and the Odyssey (1709) from ancient Greek into French. Her translations are enduring monuments of French literature, noted for their elegance. It's stunning to think that we had to wait until 2017 (!) until a woman translated the Odyssey into English, Emily Wilson's wonderful translation. The reason why we had to wait so long is that the sciences, as well as Latin and Greek, were seen as particularly difficult and effortful, and therefore not suited for women. And even now, women are in the minority among mathematicians today and star mathematicians such as Maryam Mirzakhani are extremely rare, with only two women being awarded a Fields medal to date.

In Kant's view, women should restrict themselves to easy and beautiful, rather than difficult and sublime subjects.

But Kant knew that other people thought differently. Notably, there was Fontenelle's Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, an enormous bestseller that was first published in 1686 that has since seen many, many reprints and translations. Fontenelle made the case (both in its introduction and in its general form) that women are just as intelligent and capable as men and should be offered an education in the sciences.

About Fontenelle's influence on women's education Kant wrote,

The beauties can leave Descartes’ vortices rotating forever without worrying about them, even if the suave Fontenelle wanted to join them under the planets, and the attraction of their charms loses nothing of its power even if they know nothing of what Algarotti has taken the trouble to lay out for their advantage about the attractive powers of crude matter according to Newton. In history they will not fill their heads with battles nor in geography with fortresses, for it suits them just as little to reek of gunpowder as it suits men to reek of musk.

Kant thought that it was “malicious cunning” on the part of Fontenelle and Algarotti to mislead women into science. So what and who was Kant reacting against?

The suave Fontenelle

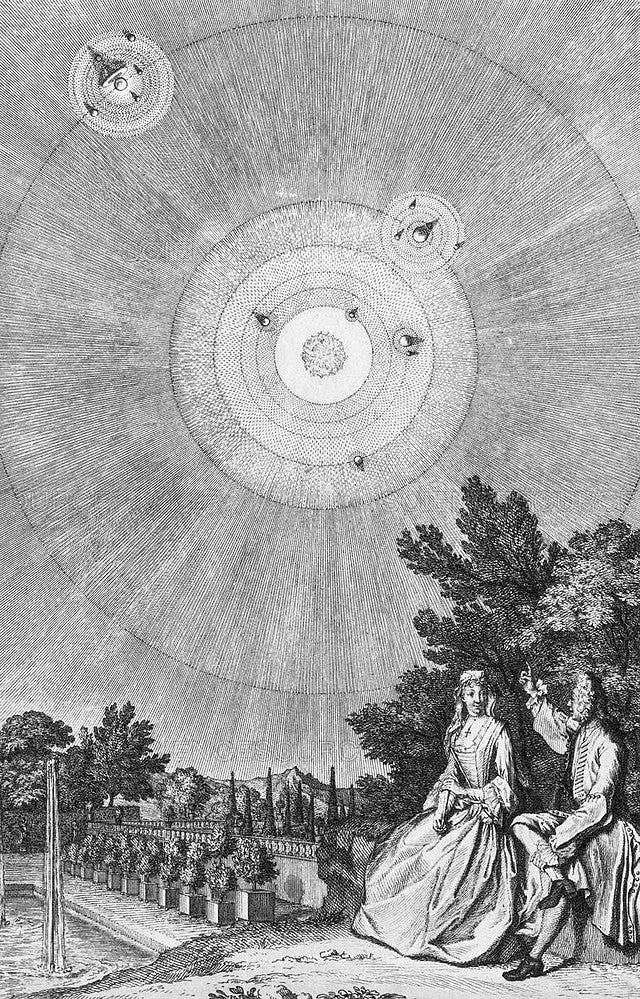

The “suave Fontenelle” was Bernard le Bouvier de Fontenelle (1657-1757), an early Enlightenment French philosopher who remarkably lived until nearly the age of 100. He wrote his Conversations on the plurality of worlds (1686) at the age of 29. A dashing young proto-feminist, he delighted his female patrons and salon hosts. The book is written in the style of a novel, and it features a series of dialogues between a Philosopher and a Marquise, conducted at her estate in the moonlight.

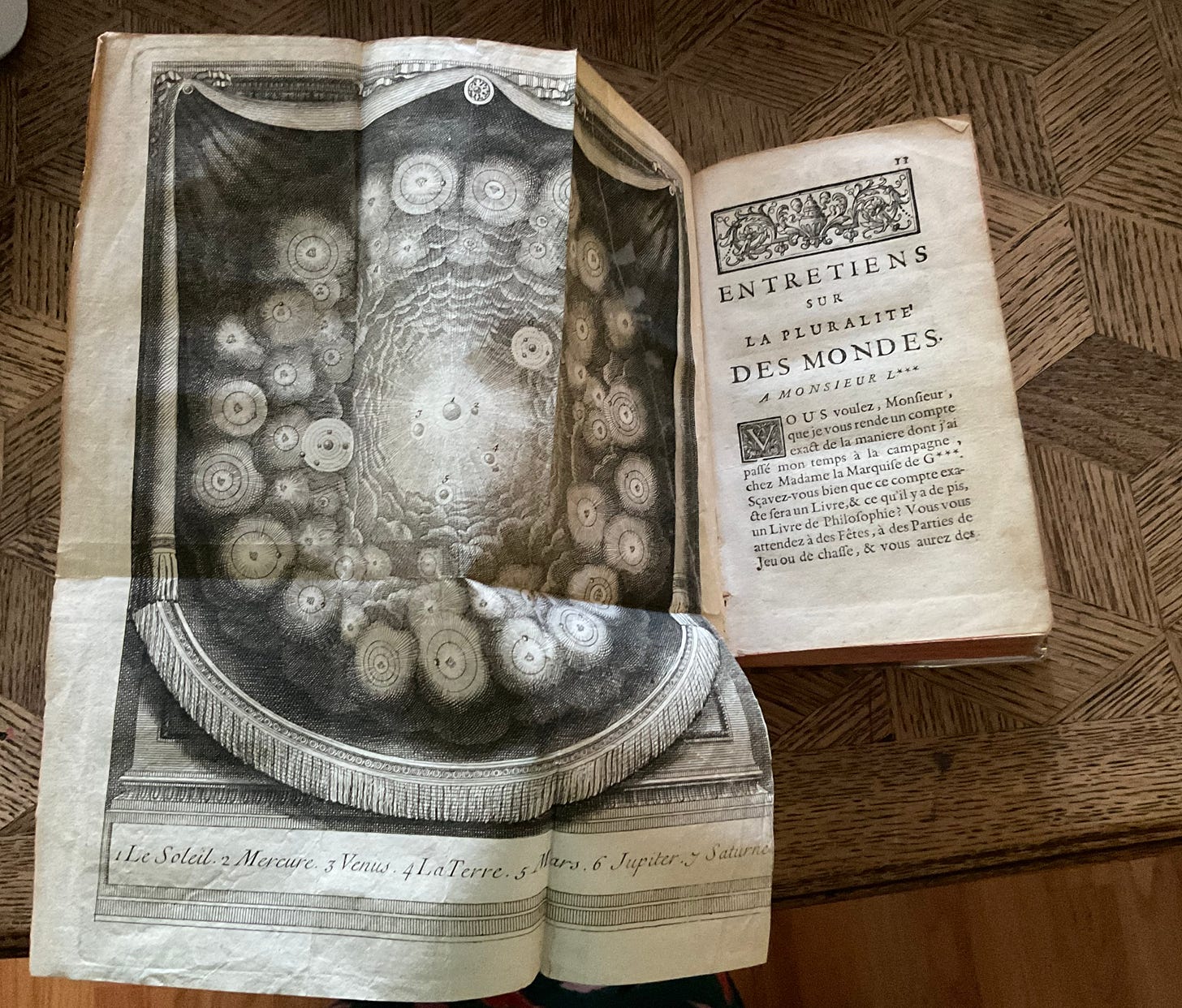

When I first read the book (in an English translation) I got so enamored with it that I wanted to have a French first edition. I could not find one, but I could buy a very fine edition from 1724, of which you can see the frontispiece here.

The frontispiece shows the plurality of worlds from the title. World in the seventeenth and early eighteenth century meant “solar system.” Fontenelle explores the conclusions of the Copernican revolution: if Copernicus is right that the Earth does not stand at the center of the universe, we must conclude that our sun is not the only sun. Or differently put, there is not one solar system but many. If there are many solar systems, and hence many exoplanets (shown in the frontispiece) then we might reasonably imagine that many alien life forms exist.

This is, in brief, the summary of Conversations, where the Philosopher gently initiates the intelligent but uneducated Marquise into Copernicanism, Descartes's vortex theory, and the theory of multiple solar systems.

It is often said that the Conversations has done more for women's education than any of the contemporary essays explicitly arguing that women ought to be educated. And Fontenelle did that simply by making the main interlocutor of the philosopher a woman (the Marquise). True, the dialogue between the Philosopher and the Marquise is playful and flirty. For example, the Marquise and Philosopher remark that the day is like a blonde, and the night like a brunette, and wonder whether the night might be more beautiful than the daytime, even though the Marquise herself is blonde.

But the Marquise is not a passive recipient of knowledge. Indeed, when the Philosopher at first is hesitant to explain to her how astronomy works (he definitely does not spontaneously go into mansplaining), she chides him “Do you think I'm incapable of enjoying intellectual pleasures?”

She is very quick in learning and comes up with objections, and she wonders about the dazzling implications of potential alien life, “here is a universe so large that I'm lost, I no longer know where I am, I'm nothing. Each star will be the centre of a vortex, perhaps as large as ours? … As many spaces as there are fixed stars? This confounds me – troubles me – terrifies me.” The Marquise's appraisals differ from the Philosopher in a way that reasonable disagreement permits: he thinks the universe is purely chance and haphazard—the Earth could've been anywhere, there is no providence (very quietly, he seems to think there is no God, but Fontenelle is not openly atheistic and in other work shows himself very tolerant about religious beliefs), she on the other hand sees nature as caring, almost maternal.

Why having a female character in Conversations matters

It was straightforward for Fontenelle would choose a philosopher as the character who explained to the reader Copernicus’s heliocentrism, Descartes's vortices and other astronomical knowledge. However, the choice of the Marquise is less obvious. At the time that Fontenelle wrote, it was unusual to have a woman feature in a philosophical dialogue. Women were commonly thought to be inferior to men (in virtue, physical ability, intelligence). Moreover, dialogues were often presented between adversaries (see e.g., dialogues written by Hume or Galileo), where different characters would defend different positions. Here, however, the discourse is more akin to a discussion between a teacher and a brilliant, quick-witted student.

Here is Fontenelle's own justification for his choice of characters (from the Preface)

I've placed a woman in these Conversations who is being instructed, one who has never heard a syllable about such things. I thought this fiction would serve to make the work more enticing, and to encourage women through the example of a woman who, having nothing of an extraordinary character, without ever exceeding the limitations of a person who bas no knowledge of science, never fails to understand what's said to her, and arranges in her mind, without confusion, vortices, an worlds. Why would any woman accept inferiority to this imaginary Marquise, who only conceives of those things of which she can't help but conceive? Fontenelle, Conversations, 1686, Hargreaves translation).

In 17th century France, a lot of discourse had turned openly misogynistic, deriding learned women as somehow silly or ridiculous. This was because men did not like the competition of women, especially wealthy female patrons of salons, in the public intellectual sphere. Women could enter the intellectual sphere especially since learning was no longer so constrained to universities (from which women were formally barred), as it was during the middle ages. In the 17th and 18th century science turned definitely domestic.

For example, Anne Marie Lavoisier, the wife of the famous Antoine Lavoisier, was the co-discoverer of oxygen and its role in chemistry and in the burning process. Marie-Anne made drawings and reports of their joint experiments (here is her drawing, showing an experiment of someone who exhales oxygen into a machine), you see her drawing and making notes on the right, so it is a self-portrait. She also translated works from English into French for her husband, and organized his posthumous writings into neat publications when he sadly was killed during La Terreur by guillotine (as an established member of the French aristocracy during the French revolution, this was a real risk).

Women were making huge advances in science thanks to the informal networks of letter-writing (which I wrote about here to

) and with salons. But learned women were derided as “bas-bleu” (blue stockings), who did not properly do the things women were supposed to do, especially take care of children and keep the house.To just give a snapshot of how effective Fontenelle was at educating women in STEM (or rather, its precursor), an article in the Guardian in 1713 remarked on one woman's household:

The excellent lady, the lady Lizard, in the 'space of one summer furnished a gallery with chairs and couches of her own and her daughters working; and at the same time heard al Tillotson's sermons twice over. It is always the custom for one of the young ladies to read, while the others are at work…I was mightily pleased the other day to find them all busy in preserving several fruits of the season, with the Sparkler in the midst of them, reading over The Plurality of Worlds It was very entertaining to me to fee them dividing their speculations between jellies and jars, and making a hidden fiction from the fun to an apricot

However, it's important to note that Conversations not only educated women. It was a tremendously influential popular science book that educated everyone, translated in several languages. Its style, based on the psychological novel, also shows how there was no steep division between humanities and sciences. For Fontenelle, the two went together. The easy style of the novel could help people come to terms with difficult technical ideas, such as Descartes's vortex theory, gravitation, planetary orbits, etc even if they lacked the mathematical abilities for it.

Francesco Algarotti's Newtonianism for ladies (1737), to which Kant also directs his ire, was written in a similar vein. On the frontispiece you can see the author and Emilie du Châtelet, who was a personal acquaintance of Algarotti, and he admired her for her deep knowledge of both physics and mathematics. The first edition in 1737 lacked the usual privileges and permissions, had a forged imprint of Naples on the title page, and soon found itself on the Catholic Church's index for forbidden books.

So what are we to make of these scientifically instructive, flirty dialogues that explain natural sciences to women? What Kant's reaction, and Algarotti's emulation, shows is that there was no homogeneity in thought about the access of women to science education. We see similar backward ideas about women's education in Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Emile (1763), who like Kant seems to think that women should be subservient for men and should not be educated (but also acknowledges women were, in practice, in charge of the earliest education of children…)

It's not the case that Enlightenment philosophers slowly opened their eyes to the dawn of reason and saw that women ought to be educated. Rather, it was a contested good. In this, the emancipation and achievements of largely self-taught female scientists, translators, and mathematicians such as Marquise du Châtelet, Anne Dacier, and Marie-Anne Lavoisier, played a crucial role. Popularizing works with female role models, like Algarotti and Fontenelle, were also highly crucial.

Philosophers like Kant who wrote misogynistic replies to these efforts were not doing so because they were, as the exculpatory language often goes, “men of their time.” For, after all, Emilie du Châtelet was also a woman of her time, and Fontenelle was a man of his time. The road to women's emancipation is not one that rolls itself out but that is contested and debated. An effective work, such as Fontenelle's Conversations could have a large, positive impact. How we communicate science matters, today as it did in the 17th and 18th century.