The Richness of Reason - part 1: for Marin Mersenne, all music is math rock

First part in a planned series on the Enlightenment and how reason was much richer than we give it credit for. Let's start with music.

Unless you're a mathematician, you've probably not heard of Marin Mersenne (1588-1648). If you are a mathematician, you may be thinking right now of the beauty and elegance of Mersenne primes, which take the form Mn = 2n − 1.

You can listen to this beautiful piece from Mersenne's time to get you in the mood or while you are reading this post.

Enlightenment, but more than what Pinker and others make of it

My intention is to write some brief pieces on the Enlightenment, which may be developed more fully later on. My main motivation is that many (non-historian and non-philosopher) scholars have a narrow conception of what the Enlightenment is. For authors such as Steven Pinker, the Enlightenment represents that period when people in Europe discovered reason, began to appeal to science, and pushed aside religious dogma. The problem with this vision is that it sells the Enlightenment short. It has a very anodyne and impoverished conception of reason.

Enlightenment authors were not just interested in reason but also, perhaps more crucially, in its limits. Think, for instance, of Immanuel Kant's three Critiques (of Pure Reason, Practical Reason, Judgment) these are all critiques of different forms of reason, including causal reasoning, teleological thinking, and proofs for the existence of God. Rather than being cheerleaders for reason, Enlightenment authors challenged the notion of reason constantly.

The popular picture also oversimplifies the relationship between religion and science. How to explain that many Enlightenment authors (Newton, Descartes, etc.) were deeply religious people? Did you know that science fiction and satire were stock elements of Enlightenment thinking (think of e.g., Cyrano de Bergerac, Jonathan Swift)? As I argue in this paper, by putting up alternative worlds like a mirror to our own, we can critique society through fiction. But Enlightenment thinkers (Fontenelle, Kant, many others) also earnestly believed in alien life. Kant wagered many finer things in life on the existence of alien life (a weird random passage in his Critique of Pure Reason).

Most of all, our twenty-first century retconning of the Enlightenment misses the fact that struggle, conflict and debate were essential to the development of science and philosophy. As Foucault already recognized, struggle and resistance are key in the development of our concepts.

Proponents of “the Enlightenment” (pop version) seem to think that if only you would appeal to reason (abstractly), then truths about hot-button issues such as race, gender etc. will reveal themselves to you through science. They think there is, for instance, a scientifically correct answer to the question of whether and how sex and gender relate, according to authors such as Pinker, and anything that does not fit their preconception is science denialism (viz his The Blank Slate: The Denial of Human Nature).

But this isn't the case! Enlightenment authors frequently disagreed with each other. Some authors such as Immanuel Kant embraced “race science” which (not coincidentally) put white people at the top of a biological order. But others, such as John Beattie argued vehemently against it.

We cannot avoid to do the work of debating these issues, and we cannot pretend that some sort of free-floating, value-free reason will unerringly give us an abstract, correct answer, conveniently free of any political or ideological lenses. Science is a tool, not an oracle, and we must decide how we put it to use. Enlightenment authors understood this.

Mersenne's Music Theory

I'll go into this (time etc permitting) in later posts, but for now, let's start with what I propose is a much richer conception of reason that Enlightenment authors had. This richness of reason included enduring concerns about how to conceptualize things like the arts and their relationship to science.

So let's begin with an unlikely figure in the scientific revolution and the development of Enlightenment philosophy, the Catholic priest Marin Mersenne (1588 – 1648). Mersenne was extremely well embedded in this milieu. Philosophers often meet him as the collector of objections and replies to Descartes’ Meditations.

What Mersenne was really interested in and where his philosophy really shines is in music theory. For Enlightenment thinkers, music theory was crucial for understanding our very soul. Music has always elicited emotions, but Baroque (at the time called “rhetorical”) music was specifically engineered to stir our passions—the music can whip us up, make us upset, but, more importantly calm our passions and help us to achieve self-control, which is critical for humans if they are to live together in harmony.

Let's dive into Mersenne's Traité de L’Harmonie Universelle (1636) which you can download for free at the ever-amazing IMSLP. The title already indicates Mersenne's concern with harmony, not just in the physical aspects of music, but also the harmony in our souls, in society, and in the very structure of the universe, which Mersenne believed is reflected in musical intervals.

Music as Mood Management

In the Preface, Mersenne argues that the”principle usage of music is to guide people to reason and to regulate their morality.” He thinks it is a great pity that music theory, compared to other fields in his days, is underdeveloped. One need but think of seventeenth-century optics and the astounding innovations of e.g., telescopes and microscopes, which afforded people a look into the vast and the tiny. But why would music matter for science? Mersenne ambitiously hoped that his musical theory would allow “Musicians to use sounds the way masters in Optics can use colors and light, so that they can appease the most furious passions of their listeners & guide them to virtue.”

Calming the passions and the excesses of behavior that arose as a result of this was a key concern for Mersenne (he was a Catholic priest, but you see this concern in a lot of 17th c European thought). Now, we want to experience excitement, but the ideal mental state for a 17th-century European was mental quietude. Apparently, they had enough excitement as-is.

Mersenne goes on to say that an accurate knowledge of music and its connections to the passions (roughly, what we now call emotions) can have medicinal use too. This was not unheard of, as in Mersenne's time you had, for instance, Tarantellas which were specifically meant to be listened to and to modulate one's emotions so one could recover from a tarantula bite (here, because the sufferer was languishing, the aim was to stir up the ill person and to revive them in this way, as you can hear here.)

Mersenne writes his Treatise in a geometrical format (we see this format also in Spinoza's Ethics, published some forty years later), with theorems that he sets out to prove. For example,

Theorem 1: Music is part of mathematics, and so, by consequence a science that shows the causes, the effects, and the properties of sounds, songs, concerts, and everything that belongs to it

So, for Mersenne music is irreducibly mathematical. Not just the score, but even the acoustic properties and the performance, everything of music can be described mathematically. It's important to keep in mind what a rich, complete art music was at the time. Opera had been recently invented in Italy, and it included drama, poetry, music, painting and mechanics (with the movement of opera props). It was hugely popular, and Mersenne must have known it.

But in Theorem IV we read:

Music is a speculative science and practice, and an art, and by consequence, a virtue of understanding that she guides to the knowledge of truth.

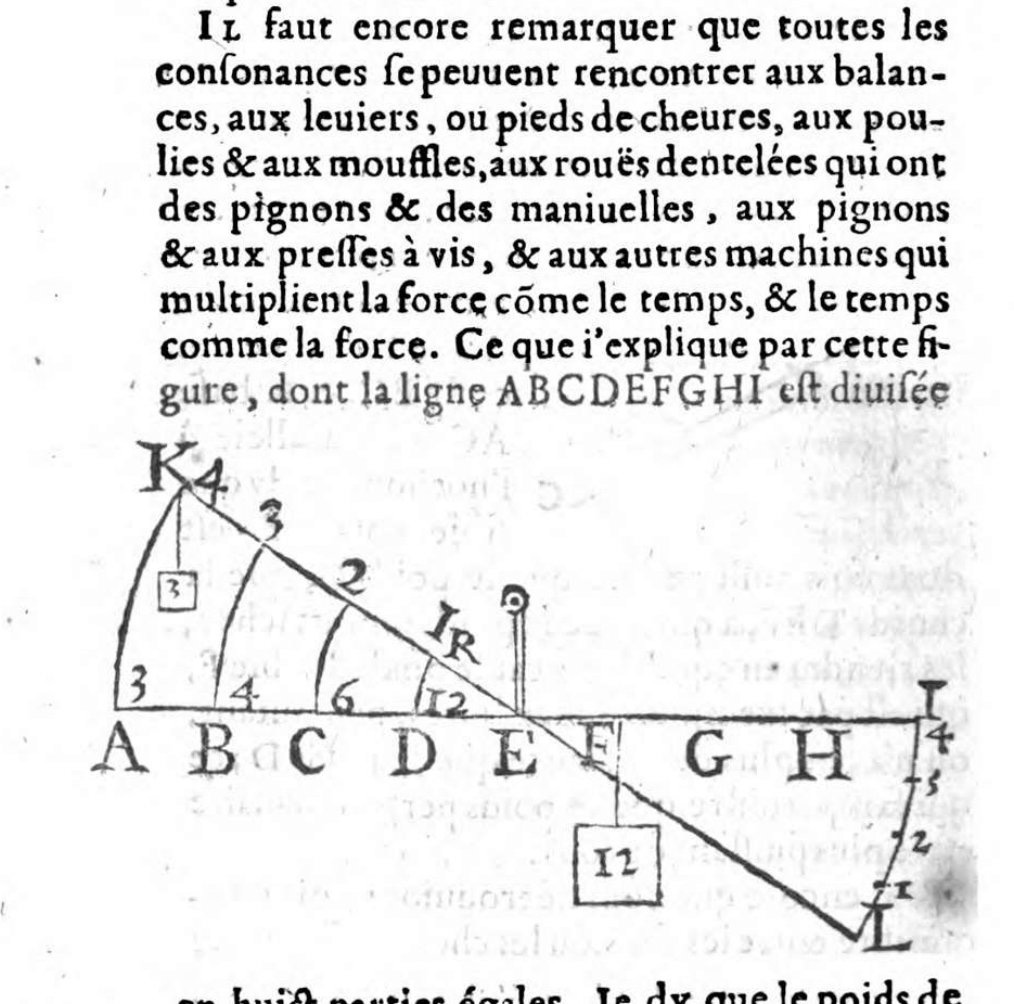

Mersenne goes on to discuss how musicians and composers require the liberal arts as well, as well as engineering, mechanics, physics. Music is a practice that blends what we would now call the humanities, science, and mathematics.

The book goes on to explain each of the theorems in great detail, supporting the main claims with examples (so it's a geometric order book basically).

A lot of time and care is devoted to the problems relating to intervals and musical temperaments. Since Pythagoras we already know it's impossible to have pure intervals where the tunings are based on the ratio 3:2, because of the fact that it doesn't add up: 12 perfect fifths do not round off to precisely an even octave. In Medieval music this wasn't too much of an issue. But rhetorical music (and Renaissance music, which preceded it) used increasingly complex, colorful intervals, such as diminished and augmented chords, and a much increased use of thirds, sixths, ninths etc. and it was not feasible to use this tuning anymore (listen to this piece by Robert de Visée, a contemporary of Mersenne, below to get a sense). So, the question was how to cut up an octave so that it all sounded good and was feasible to tune.

Music and Astronomy

In addition to temperaments and tunings, Mersenne explicates (as he said in Theorem III) that “Music is an intellectual virtue.”

This is because of the principled nature of music as a discipline, with the relationships between different intervals, modes, harmonies etc. It is deeply mathematical in nature, and you need to use the mathematical relationships and logic (hence, reason) in order to stir and quieten the passions of your listeners.

Music also gives us intellectual virtue, because (in Mersenne's view) a good musician must know grammar and logic because of musical structure, arithmetic because of intervals, physics because of acoustics, rhetoric, because in music you must achieve non-verbally what public speakers achieve in spoken language by the use of rhetorical devices such as foreshadowing, repeating etc.

And a musician must also know astronomy, because, obviously (well to Mersenne, not to us) musical intervals and relationships are reflected in the motions of the planets and the stars.

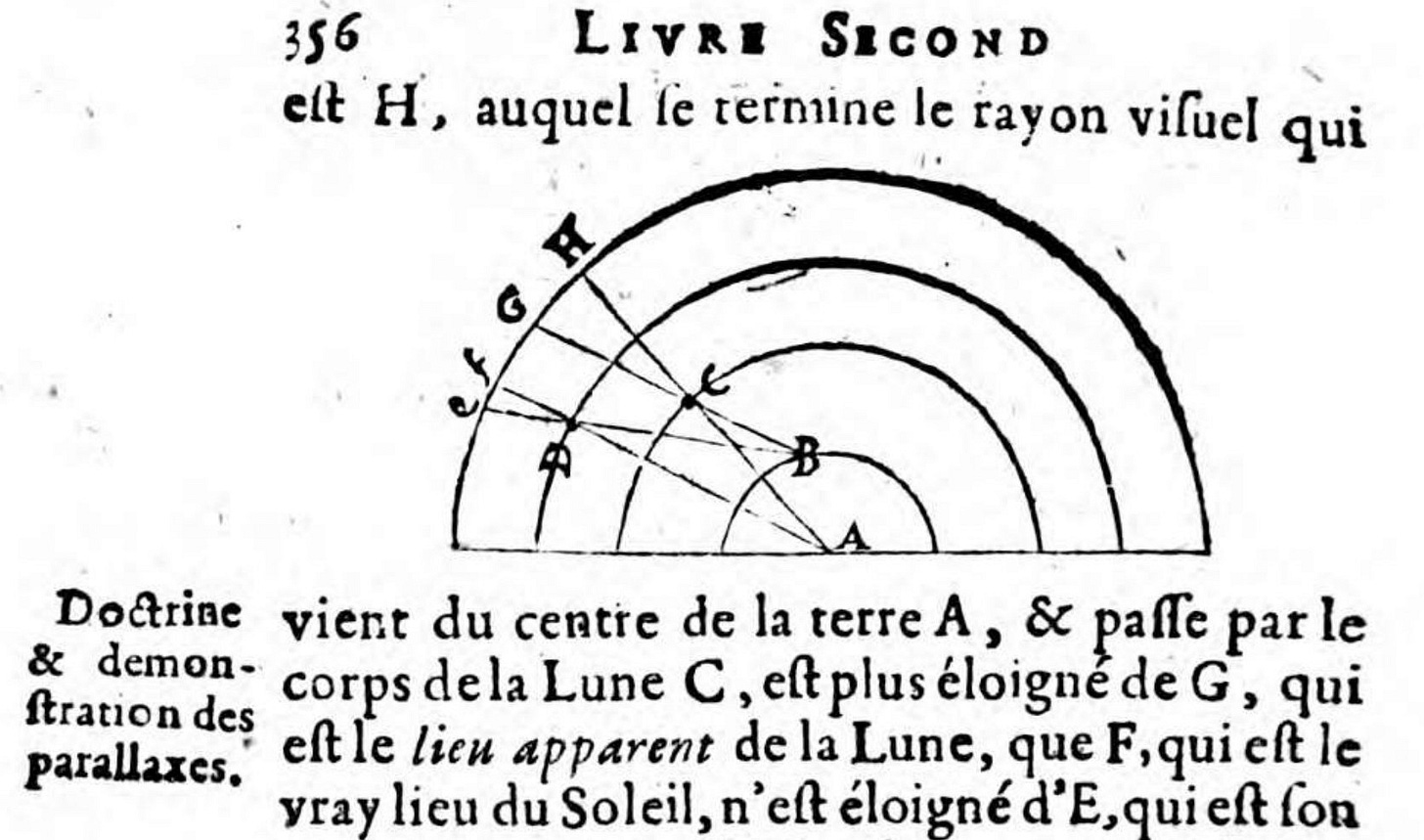

These relationships between heavenly bodies and music are further explicated in Book 2. Here we see a kind of Platonist vision of the planets and their relationships that reminds one of Johannes Kepler, the astronomer, who likewise took the music of the spheres literally. Mersenne considers both Tycho Brahe's and Copernicus’ new systems as options/pictures of the universe, so he has left behind geocentrism (also note we are well into the 17th century).

Mersenne imagines the planets as being part of a concert and so you need to give them all their parts, the bass to Saturn and Jupiter, the contralto to the earth and Venus etc, as seen below in the schema of the individual melodies given to the different heavenly bodies (the Moon, Mars, Venus etc).

He then draws extensive parallels between music and geometry. This just goes to show, when we nowadays talk about the scientific revolution, there's often a danger of projecting how science now works back onto the early moderns, as if they did science the way we do now, except with less knowledge. We sometimes become aware that this isn't the case, since, for instance, it is well-known that people such as Newton dabbled in alchemy, and that even for Robert Boyle, one of the founders of modern chemistry, the line between alchemy and chemistry wasn't so clean.

Early modern authors saw connections we do not see. They expected distances between planets to reflect musical distances. They saw parallels between chemistry (alchemy) and music, medicine and music, etc. that we simply do not see. Now, with the wisdom of hindsight it's easy to say now: Why should we expect the distances between the planets in our solar system to reflect musical distances?

Why not? Mersenne's Treatise on music shows how early modern authors thought about the relationships between their budding sciences in a holistic and speculative way. It also shows how they thought of the practical aspects not just of engineering and science, but also of music (considered a science) for the development of human virtue and society. If music can help a musician or composer to influence the passions of his audience, then music can be like a medicine, not just for an individual person, but for society as a whole. Here, we have another platonist echo, for in the Republic music is also seen as a key element for the furthering of collective virtue.

“let's start with what I propose is a much richer conception of reason that Enlightenment authors had. This richness of reason included enduring concerns about how to conceptualize things like the arts and their relationship to science.”

To me, this is the crux of where modern science has gone awry; the separation between art and science has brought with the latter a certain air of pretence, superiority, as if it's the sole province of geniuses. This false superiority undeservingly makes it unapproachable for the general populace.

Thank you for shedding light on this important topic.

Thanks much for this interesting piece on one of the attempts to align ancient planetary polytheism with the inchoate rationalism of the early Enlightenment period. The overlap of the two ways of thinking is of course an enormous scholarly playground, less policed now than formerly. I question whether Descartes was a religious believer. Pascal took him for an undeclared atheist, and with the example of Bruno before him his paranoia was justifiable. The reconciliation attempts continue unabated among astrologer with very limited success. Even I have a theory!