I fell in love with the baroque music repertoire a few years ago, shifting my musical interests from the Renaissance to the 17th and early 18th century. I am learning to play baroque repertoire on my lute (an archlute, soon a baroque lute, which is being made for me), while also trying (not always successfully) to inhabit the mindset of what it takes to play this very tricky music.

Trying to inhabit the baroque mindset has helped me to look at the philosophy of that time with fresh eyes. Consider the “baroqueness” of Descartes's fugue-like building of an entire universe from the simple theme of a cogitating self, or Leibniz's monads, very baroque indeed with their splendor and variety, as you can see in excerpts like these—

Now this connexion or adaptation of all created things to each and of each to all, means that each simple substance has relations which express all the others, and, consequently, that it is a perpetual living mirror of the universe.

And as the same town, looked at from various sides, appears quite different and becomes as it were numerous in aspects; even so, as a result of the infinite number of simple substances, it is as if there were so many different universes, which, nevertheless are nothing but aspects [perspectives] of a single universe, according to the special point of view of each Monad.—Leibniz, Monadologie, 1714

The changes we see in philosophy in that period, with the shift to “experimental philosophy” or “the new science” (which we now with hindsight call the scientific revolution) are also interestingly reminiscent of the changes we see when music in Europe transitions from Renaissance to Baroque.

Baroque music at the time was not called baroque but “rhetorical music,” and it was called this because it uses techniques from classical rhetoric to evoke emotions (“passions”) in the listener. In this way, it aims to allure the listener, quieten their passions, and maybe—in some cases—transport their soul to virtue (see my earlier post on Marin Mersenne, here).

The mood managing through music echoes developments in other fields from the late Renaissance and early modern period, notably theater and politics. Machiavelli, like Shakespeare, emphasized the primacy of appearance over reality and of the great force of emotions in guiding people's actions. If emotions are what matters, then music (and art more generally) can be a way to guide people's emotions in ways we deem desirable.

Here's a neat piece by Robert de Visée played by the inimitable Toyohiko Satoh to give you a feel for the rhetorical scope of these pieces, even on a single instrument.

Baroque music has a lushness and graininess to it, a rhetorical force that sets it apart from the serene, calm and measured Renaissance repertoire. The music sighs (as in the sarabande), it whispers, groans, or it darts and speeds (as in a courante), but it does so while centering the listener, rather than the player. The player deliberately places herself in the background and plays with virtuosity but without showiness (as this lute manual by Mary Burwell, a 17th century female lute virtuoso indicates). The composer too weaves magic (think especially of JS Bach), but you need to really dive deeply into it to uncover the structure and to see it. This is what distinguishes its deeply emotional character from later romantic music.

I find a lot of interesting concordances between 17th-century music and early modern science, as already remarked by theorists on the baroque such as Severo Sarduy, who remarks:

The single center of the stars’ orbits, previously supposed as circular, vanished, only to double itself when Kepler proposes the ellipse as the figure of this displacement; Harvey postulates the circulation of the blood; and finally, God himself no longer seems to be a central, unique, given, but rather the infinity of certainties of the personal cogito, dispersion, pulverization that announces the galactic world of monads. — Sarduy, The Baroque and the Neobaroque (1972)

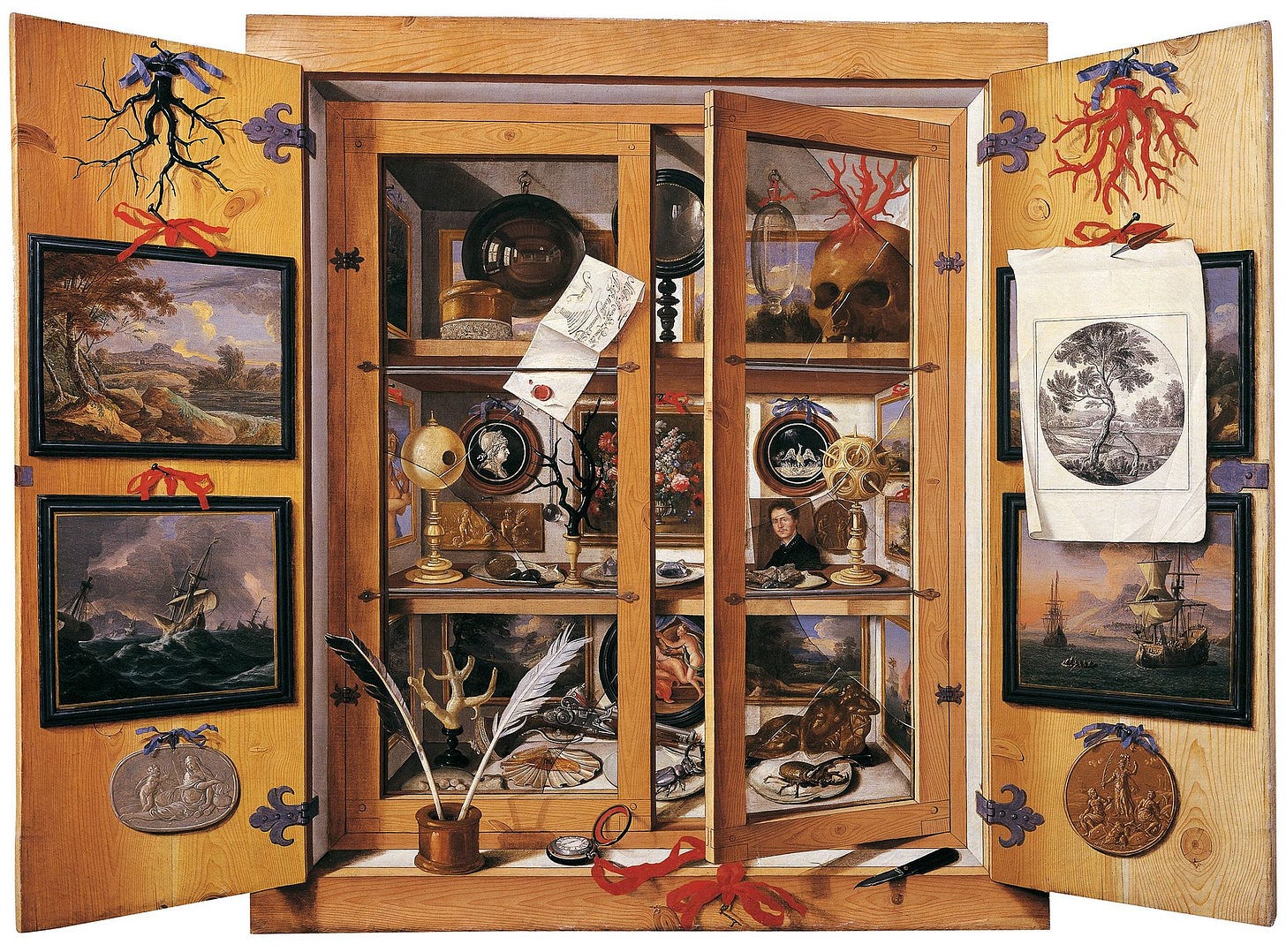

Whereas medieval and Renaissance natural philosophy and music was smooth, concerned with regularities and intricate counterpoint, Baroque music and the new science from the 17th century were what Daston and Park call “grainy,” full of weird shapes and unusual chords.

If you play baroque music too smoothly and evenly, you do not do it justice. Notes inégales (unequal notes), the natural alteration of “bad” and “good” notes and other features make the music inherently imbalanced. This all reaches its zenith is in the opera, a quintessentially baroque art form where theater, costume, painting, music, rhetoric, and engineering come together.

In the Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, an elegant conversation between a marquise and a philosopher on the topic of astronomy, the philosopher makes an explicit comparison between discerning the mechanics of an opera house and the discerning work of the philosopher (note at the time the word “scientist” was not in use yet, so early scientists were called philosophers):

On this subject I have always thought that nature is very much like an opera house. From where you arc at the opera you don't see the stages exactly as they are; they're arranged to give the most pleasing effect from a distance, and the wheels and counter-weights that make everything move are hidden out of sight. You don't worry, either, about how they work. Only some engineer in the pit, perhaps, may be struck by some extraordinary effect and be determined to figure out for himself how it was done. That engineer is like the philosophers. But what makes it harder for the philosophers is that, in the machinery that Nature shows us, the wires are better hidden—so well, in fact, that they've been guessing for a long time at what causes the movements of the universe. —Fontenelle, Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, first evening

Here, you can contrast classical forms of art with their central, organizing principles to baroque imbalance, the “multipolarity that allows the rich and turbulent sources of the unconscious to overflow.” (d’Ors). The natural philosopher makes theories and then applies these to nature, on the other hand the scientist looks at nature first and then tries to make sense of it. As Eugenio d’Ors (another theorist on the baroque) put it, classicism is “normative and authoritatian", but “the Baroque is vitalist, it is freedom-loving; it entails self-abandon, and honors strength.” Here d’Ors makes an astute observation on the fugue, which is built around a central theme and develops it in several open-ended ways, with modulations and different speeds,

It is useful to note that in the artistic realm, classical forms prefer what in musical terms is called counterpoint, a closed system that gravitates around an internal nucleus, whereas Baroque forms prefer the pattern of the fugue, an open system that follows an attraction to an external point.—Eugenio d’Ors, Lo Barroco, 1944

I'll end this probing piece (more a toccata than a fugue, alas) with this beautiful poem by the Mexican Baroque era poet and philosopher Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz:

green fascination of humanity, Mad hopefulness, frenzy in gold ornate, Dream of the ones awake so intricate, As is with dreams, the treasures vanity. Soul of the world, abloom senility, Decrepit greenness in imagined state, Today for all the happy ones in wait, Tomorrow that the hapless long to see: Let trail your shadow in search of your day those who, With lenses green for glasses plain, To their desire see things drawn totally; For I, in fortune mine more wise today, In my two hands both of my eyes retain, And only what i touch do i then see. -- Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, translated by Carl W. Cobb** ** This and other quotes come from the alluring book Baroque New Worlds edited by Lois Parkinson Zamor and Monika Kaup, which focuses on the baroque as an aesthetic, but especially writers from Latin America who have appropriated the baroque as a uniquely Latin American aesthetic. I may write on this in the future, as I find it fascinating!

Your parallels between theatre mechanics, philosophy, and science are fascinating. It reminded me of how Mannheim described how the philosopher Erich Kaufmann showed that the term "organism" appears to have been first used in a political and social rather than a biological context. According to Mannheim, Kaufmann traced the origins of the modern concept of "organism" back to Kant. It turned out that philosophers who worked mainly in the field of law used this term in a sense close to the modern concept of "mechanism" and related to ideas about systems assembled by masters for specific purposes and not living beings with their spontaneous development. But all of them, unfortunately, had no thoughts on music as you have))

Very thought-provoking!

I've never formally studied music theory, so I hope I can express this properly:

Few would dispute that, today, the most well-known baroque composers are Vivaldi and J.S. Bach. While I have to concede Bach was the more versatile of the two, lately I enjoy listening to the Venetian more.

Bach's music feels like an intricate, beautiful clock constructed by a brilliant artisan, crafting the parts from his own genius.

With Vivaldi, it's as if the music is a force of nature the composer has managed to channel for our delight -- an underground stream that emerges, dazzling, from the jets of a gorgeous fountain.

Or something like that😜