Letters on evil (part 4, final part)

Where our philosophers finally meet face to face, and Spinoza writes a Dear John letter

After all the drama in previous letters between grain merchant Van Blijenbergh and lens grinder and philosopher Spinoza (installments of the first, second and third pair of letters linked), the final two letters are a bit of a come down. We learn from the letters they have finally met in person.

Van Blijenbergh seems to want Spinoza to reveal his entire project of the Ethics to a potentially hostile reader, and Spinoza is just so fed up with him that he writes him a letter to desist from further writing. This is the final letter between them.

Overall, the correspondence has been fascinating both from a psychological and philosophical perspective. As Deleuze writes in Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, these letters are “the only long texts in which Spinoza considers the problem of evil per se, risking analyses and statements that have no equivalent in his other writings.”

Van Blijenbergh's continued badgering and asking for clarification has forced Spinoza to carefully lay out his positions. Also, intriguingly, while he states in his second letter already that they won't be friends, and writing has no further point, it seems like he can't stop himself from continuing this correspondence at least for a while.

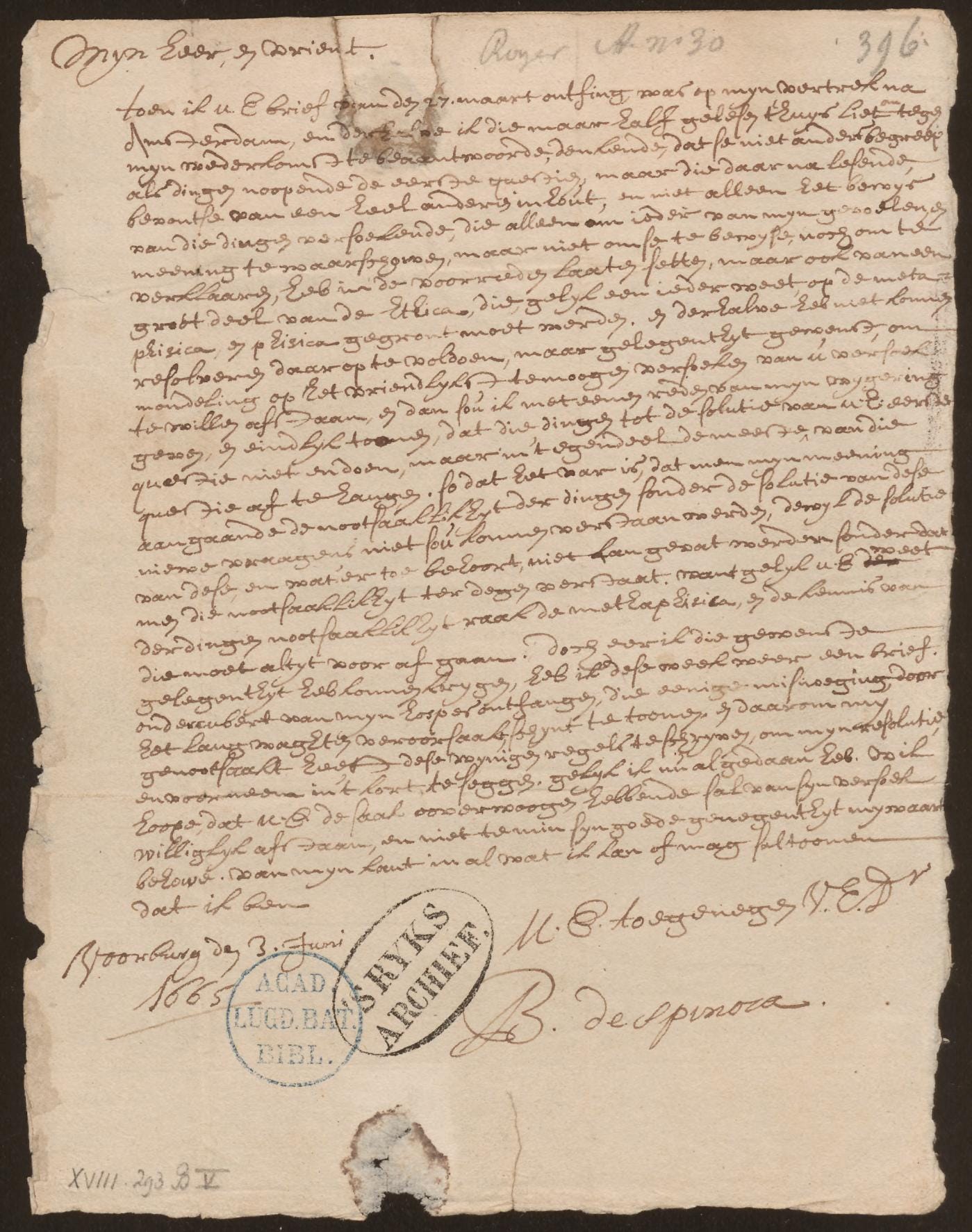

But by this time (letter 8), Spinoza's clearly had enough. You can see the autograph of that Dear John letter above, one of about 10 surviving autograph letters by Spinoza.

To our knowledge Spinoza never started a correspondence, and his number of surviving letters is tiny compared to others of the period—hundreds by Descartes, thousands by Leibniz. But somehow, even though there are fewer than 100 letters (to and from), they speak to us in a sparkling prose and they give us a fascinating snapshot of the times.

Van Blijenbergh has often been portrayed as a fool, but many of his remarks, for example, about how you can make sense of virtue in a deterministic world, are questions my grad students (who are all smart) also raised in our slow-reading the Ethics seminar.

Spinoza was very hesitant to share his Ethics with people outside of a small circle. He was worried (justifiably) the contents could land him in prison or worse, and even Leibniz was unable to see the manuscript before it was posthumously published, in spite of multiple attempts and entreaties. In light of this, and of Spinoza's extreme reluctance to share more with a hostile audience, we can understand why he broke off correspondence at this point.

Letter 7, Van Blijenbergh to Spinoza, March 27, Dordrecht

Sir and friend,

When I had the honor of being with you, I didn't have enough time to discuss everything, and I lacked the memory to remember all we discussed. At the first docking place, I took out pen and paper and tried to write down as much as I could remember, and I realized that I only remembered a quarter of it. So please excuse me to bother you one final time with some questions: In your discussion of Descartes's Principles, which opinions are his, and which yours? Do you think evil exists, and if so, what is it? What do you mean that our will is not free?

Also, you haven't explained to me how knowledge of God and our desire to possess it originate. Why is, in your view, killing not as conducive to blessedness as stealing? You might say that you discuss all of this in your Ethics. But since I don't have this book, I'm left with perplexities I cannot resolve. Could you please briefly explain your most important definitions, axioms, and propositions? I know that will take a lot of time and efforts, and I wish there were some way I could compensate you for it. I don't want to press you to answer me quickly, but if you could do it before you went to Amsterdam, that would be amazing.

Your righteous and willing servant,

Willem van Blyenbergh

Letter 8, Van Blijenbergh to Spinoza, June 3rd, Voorburg

Sir and friend,

I only half-read your letter from March 27, because I was about to leave for Amsterdam. At first I thought the letter just asked for some clarification. But then it turned out you wanted me to explain large parts of the Ethics to you. I was looking for some occasion to ask you in person to desist. I'd then also explain to you the reasons for my refusal. But then I received yet another letter under cover [i.e., a letter that is addressed to someone else who then gives it to the intended recipient] from my landlord. There you seem unhappy because your previous letter went unanswered.

Because of that letter, I'm now writing to you to let you know my intentions. I hope that you will refrain from asking me for further clarifications, and will nevertheless retain your affection for me.

For my part, I'll show to the extent that I am,

Your affectionate friend and servant,

B. de Spinoza

Unlike Joe, I can’t help but pity Van Blijenbergh. To me, it feels like he is trying his best and Spinoza keeps putting him down!

These posts have been of great interest to me. I’m no philosopher but this summer I read a great deal of and about Spinoza: background studies for a series of poems I have been working on for some time. The sequence includes a poem supposedly in the voice of Spinoza’s fellow philosophers and other correspondents. I have considerable sympathy Spinoza in his impatience with Van Blijenberg although frankly VB seems to have exposed a central nerve in Spinoza's corpus.

The poem I mention ends with these couplets:

“Our questions multiply. Our quills dip anxiously and write.

We press our correspondent to show some route

By which we may live – he offers self knowledge and peace

From knowledge of God, all passions and struggles surpassed.”

I'll spare you the rest, but I thought it might interest you to hear how your posts can be of wider instruction and help than you might have guessed.