The Richness of reason IV: The influence of Native philosophies in Franciscus van den Enden's radical idea of egalitarian democracy

(Note: this piece reflects collaborative research with Johan De Smedt in progress on Spinoza and Native philosophies)

Centuries before the French revolution and its motto “Liberté, égalité, fraternité,” the Flemish/Dutch philosopher Franciscus van den Enden (1602-1674) proposed a radical idea of democracy that embodied the very ideals of liberty, equality, and solidarity.

In this, he was inspired, among others, by detailed reports of Native American societies. These reports of New Netherland showed a different way of life was possible: a society in which people were not dominated by those with more wealth or social rank, where gender equality was possible, and where important collective decisions were made through a democratic, deliberative process.

Franciscus van den Enden

We know van den Enden primarily as Spinoza's Latin tutor, but he was a political philosopher who is interesting in his own right. He and Spinoza influenced each other, and a lot of scholarly debate centers on who influenced whom, but I'm leaving all of that to the side for what follows. (See work by Willem Klever, Herman de Dijn, if you want more on this).

Van den Enden founded his Latin school in De Singel, Amsterdam in 1652. After being kicked out by the Jesuits for showing too much interest in women (apparently), he moved to Amsterdam where he first tried to set up an art shop (which went bankrupt). Then, he went on to found his school. One of his pedagogical principles was that Latin should be learned by speaking it. To this end he had his pupils act out classical theatrical pieces, and at least one play he wrote himself, Philedonius.

The school was attended by Amsterdam merchants, their children, and other middle-class people who wanted to expand their intellectual horizon and read classical literature and contemporary science. Knowing Latin opened up a world for you, helped you to become part of the intellectual debates in politics, philosophy, and especially science, much like knowing English as a second language today. This is why Spinoza attended Van Den Enden's school; this allowed him to write works such as the Ethics (1677) and the Political-theological treatise (1670) in Latin. Van Den Enden also was in favor of gender equality, in marriage and in the public sphere. His daughter taught at his school. He had female students, who played the women's roles in his theatrical performances (rather than boys dressed up as girls), something that scandalized the Calvinists.

New Netherland—Native political philosophy

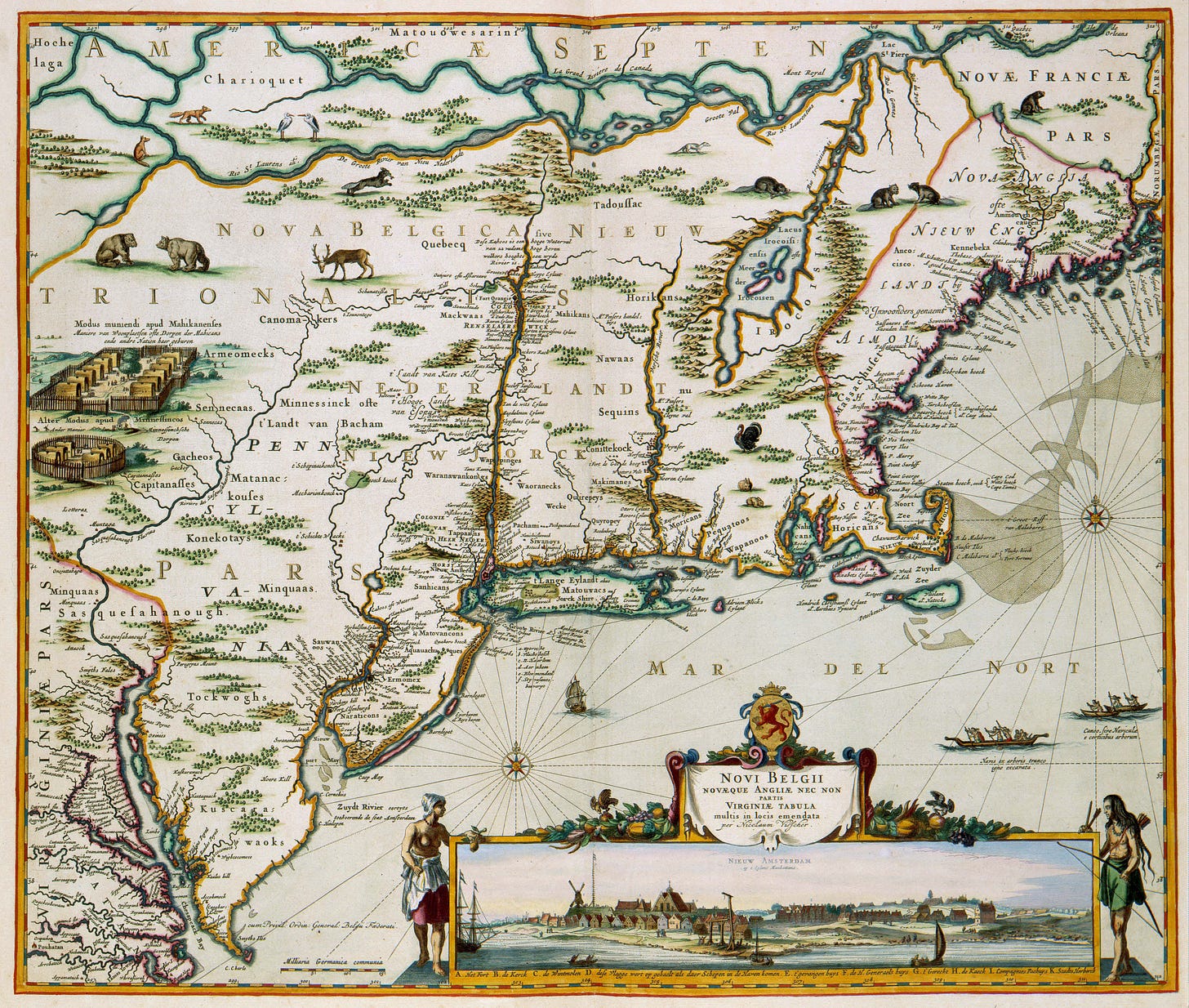

Van Den Enden was a radical democrat. One of his major projects was to help found a settlement in New Netherlands based on radical utopian ideals. New Netherlands was a Dutch settlement in Manhattan and Long Island, the banks of the Hudson, the Delaware, and the Connecticut Rivers (see map) which had grown considerably since it was founded by the Dutch West India Company in 1624.

Unlike later Enlightenment thinkers, van den Enden did not think the Dutch settlers should copy European norms and customs in their new American home. He did not believe Dutch norms were obviously superior to those of the Native Americans, as later thinkers believed, who aimed to “civilize” those they considered uncivilized.

Rather, van den Enden thought the Europeans should learn from Native American political structures, which he discusses in his book Kort Verhael van Nieuw Nederlants Gelegenheit (1662), or Brief account of the New Netherland's Opportunity, Virtue, Natural Privileges, and special Abilities of the population.

Van den Enden had not visited New Netherland but was closely associated with its political developments and he had carefully read several eyewitness reports of Dutch authors who had lived there, notably Adriaen Van der Donck’s Discourse of New Netherland (Vertoogh van Nieu-Nederland, 1650) and Description of New Netherland (Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant, 1655), and David Pietersz de Vries’s Brief History (Korte historiae 1655).

The first part of Kort Verhael is a detailed examination of the natural geography and climate of the area. Then, he goes on to describe the Native people of New Netherlands, which he calls “Nieuw Nederlandse Naturellen” (Naturellen roughly means Natives or Naturals). He describes them physically, as well as their customs, in very positive terms. He praises their freedom in marital relations, among others. He praises their manners, “We do not hear cursing, swearing and other untempered passions among them” (“Vloeken, zweren, schelden en dergelijke ongestumige passien hoort men onder haar niet”)*

In daily life and in interactions among themselves and with Dutch settlers, the Naturellen are "by nature very free and magnanimous" (Uit ‘er natuur zeer vrij en edelmoedig van aart”).

Crucially, they did not “tolerate dominion over them, and they are very much against any narrow supervision” (“Geen heerschappij over zich kunnende verdragen, tegen dezelve met alle nauwe toeverzicht zijn gekant en ingespannen”).

Anticipating later works, he writes that the Native Americans express surprise at the inequality among Dutch settlers:

Concerning the distinction between people among them it is nowhere as big as it is among us. They say frankly that they regarding our governments cannot understand how one human being can be so much greater than another.

Zijnde het onderscheidt der mensen onder hen nergens na zo kennelijk of zo groot as onder ons; zij zeggen ronduit dat ze ten opzichte onze overheids respecten niet kunnen verstaan dat den eenen mens zo veel meerder te zijn als den andere (p. 19)

Regarding marriage, van den Enden discusses how most men marry one woman, though wealthy or successful individuals can marry three or four. Marriage is a contract that can as easily be broken as it can be entered into, the moment it becomes inconvenient for one or both parties:

Among them are no marriages so fast or binding that they cannot (if one of them, either man or woman, has an extramarital affair, or a misstep [misverstand, maybe also could be translated as “misunderstanding”] arises that causes so much displeasure) immediately dissolve the marriage by one or both [parties], and is indeed completely broken. Divorce is a very common and habitual thing there.

Onder haar en zijn geen huwelijken zo vast of bondig die niet (als een van beide, hetzij vrouw of man zich met een andere te buiten gaat, ofte enig ander misverstand ontstaan, dat zodanig misnoegen veroorzaakt) van stonden aan bij een ofte beide gebroken kan werden, en ook volkomen gebroken werd. Het scheiden is daar heel gewoonlijk en gebruikelijk ding.” (p. 22)

About democratic decision making, van den Enden is clear that though there are tribal elders and chiefs, important and weighty decisions require the consent of the entire community. Not in a single vote, but in a slow and deliberative process. As he writes,

Their government is regarded as free and entirely popular, with the principal authority lying with the chiefs, nobles, and the tribal and clan elders. Only in matters concerning warfare did the war-chief get recognition [this was not unusual to have a chief especially for times of war and one for times of peace]. Everyone deliberates and decides together. The local authority either rejects it or accepts it and then carries it out. Weighty matters were very slowly and maturely deliberated by them.

Dat wijders aangaat hare regering/werd gezien vrij en geheel populair te zijn, bestaande 't voornaamste gezag bij den oversten, edelen, en oudste van de stammen en geslachten. In oorlogs-zaken werden de krijgsoverste en ook anders niet gekend. Deze an alle tezamen beraden en besluiten, en de gemeenten of verwerpt her, of neemt het aan, en voert het dan uit. Gewichtige zaken werden zeer langzaam en rijpelijk bij henlieden overwogen (pp 21-22).

The Dutch settlers should do well, according to van den Enden, to emulate these customs. To be free of domination by others, to deliberate together, to be equals, and to help each other through mutual aid. There is no reason to use what Native philosophers such as Burkhart call “delocalized thinking,” which is simply taking uprooted European structures and mistaking them for universal guidelines you can use anywhere.

Rather, Dutch settlers in America should imagine their philosophies very differently, drawing on Native political structures, and living peacefully with their Native neighbors, without trying to dominate or enslave them. Indeed, one of van den Enden's principal sources is the Dutch settler David Pieterzsen de Vries. He negotiated extensively with Native American neighboring groups, tried to prevent them being massacred by settlers (in vain, and he wrote harrowing descriptions later on), and continued to advocate for peaceful relations. He, like van den Enden, argued against slavery and for peaceful co-existence.

The resistance against acknowledging Native contributions to Enlightenment thought

The story seems straightforward thus far: van den Enden, in his political theorizing, used Native ideas and philosophies (as he could glean them from his sources).

If you read philosophers anywhere from the 16th century to the 18th century, it is not uncommon to see Europeans routinely acknowledge the influence of non-western philosophies in their thinking: Leibniz on the yijing (also romanized as i ching) as an inspiration for binary notation, Renaissance philosophers such as Ficino and Pico della Mirandola on Egyptian hellenistic philosophy. The phenomenon is broader: Baroque musicians saw the source of their new rhetorical music, with strong melody lines and strong rhythms and a pulsing baseline (continuo) in Native music. Entire forms such as the chaconne, the sarabande, and the canarios were said to be influenced by Native music, as you can hear below.

However, in the centuries that followed, scholars have systematically denied these early modern testimonies as fabrications and projections. The scholarly consensus seems to be that these supposed Native interlocutors were no more than sock puppets, projections of European fantasies, nothing more than Thomas More's Utopia. So, for example, Marrigje Paijmans writes,

In the Brief Account Van den Enden does not provide a faithful representation of the Native Americans, but rather manipulates earlier descriptions to offer his controversial political views in a veiled manner. From a postcolonial per- spective, Van den Enden’s representation can be considered a “projection” of Spinozist ideas onto Native American society, the “indigenous other” functioning as a “projection screen” for Eurocentric thought.

She does not provide a justification for this claim. Instead of Native influence, she sees the influence as Spinozist.

On the face of it, it's laudable to save people from being mere projections. There is indeed a risk that the Native “other” becomes reduced to someone who is used for instrumental ends, a projection and an imagination.

But in these retellings and systematic denial of what early modern sources clearly said over and over (namely that they were influenced) also lies a risk of erasure. There is also a risk in narrowing of the concept of reason, where only white male Europeans (as Burkhart writes in Indigenizing the land) are active contributors to Enlightenment thought. Anything else must be a projection! After all, the Enlightenment is a white, male endeavor. Or so the general thought goes.

We have seen a recent challenge to this erasure, not by philosophers, but by two anthropologists, David Graeber and David Wengrow's Dawn of Everything (2021). The book begins with the thesis that Native philosophies, particularly the notion of freedom and sovereignty of the self, played a crucial role in the development of Enlightenment thought. Their main case study were the dialogues between Adario (a Wendat chief, real name: Kondiaronk) and the French explorer and soldier Louis-Armand de Lom d'Arce de Lahontan.

Given that the history of philosophy has been a systematic retconning of any non-western influence out of the canon, as described by Peter Park in his book Africa, Asia and the History of Philosophy, I am sympathetic to Graeber and Wengrow's exhortation to look again. So, it is useful to look again at van den Enden's use of Native American examples in his conceptualization of democracy. For one thing, early settlers such as van den Enden cites had no elaborate colonial structure in place. Even if the authors of these travelogues and reports harbored racist ideas, they still needed to learn to negotiate and live together with Native neighbors.

We can see this clearly in Van der Donck's account, one of van den Enden's principal sources. He is very unsympathetic to the Native American populations he encountered, calling them savages, but he also acknowledges that they gave him vital information, for instance on agriculture. He writes,

It has happened when I was doing ... various kinds of business with the savages that one of them said to me when we happened to stand near a young wood, "I see that you are clearing that piece of land to cultivate it. It is very good soil and bears corn abundantly-which I well know because it is only 25 or 26 years ago that we planted corn there and now it has become wood again.”

Het is gebeurt a/s ick met eenige Wilden ... van diversche saken diversch propoosten hadde I een van haer-lieden teghens my seyde (soo a/s wy b occasie ontrent een jongh Bosch stonden) ick sie dat ghy dat landt doet k/aer maken I om te gebruycken I ghy sult wel doen I 't is seer goet landt I en draeght swaer koorn I dat ick wel wete I want het is noch maer 25 of 26 Jaren geleden I dat wy daer koorn op planten I en nu is het weder Bos geworden [pp. I5-i6], translation Ada van Gastel.

It very telling that when van der Donck was translated in the 19th century by Jeremiah Johnson, he mistranslated the account. Johnson suggests that the Native informant in fact got information from the Dutch colonizer on where to plant corn. This makes no sense, as Ada van Gastel points out, but it shows the steady shift of colonialism to be increasingly removed from the contributions of Native people to European thought. The corn episode also shows how routine it was for even unsympathetic people like van der Donck to learn from Native sources about agriculture, medicine and many other topics. Is it hard to imagine that these travelers would have wholly invented the political structures of Native people whom they encountered in their everyday life.

As Brian Burkhart points out, one aspect of colonialism is the denial of agency to Native people,

The Indigenous subject’s lack of the capacity to make choices and strategies toward self-articulated goals make it impossible for the Western readers to understand Indigenous writers or speakers outside of the binary lens of authenticity and inauthenticity. It is the only kind of question that can be asked of the voice of the pure affectable “other” (Burkhart, Indigenizing Philosophy through the Land, p. 76)

As Burkhart says, we don't ask whether Foucault was “authentically” French. But contemporary and past Native authors are routinely scrutinized for the extent to which they are authentically representatives of “their culture.”

We can add, when it becomes more difficult to discern the influence due to lack of written Native sources and the only ones we can read are through European settlers and travelers in the Americas, it becomes easy to dismiss their agency altogether or reduce it to a binary authentic/inauthentic.

Such a binary negates the possibility that van den Enden really was influenced by Native philosophies (indirectly) but that he also told the story to suit his own democratic ideals, his desire to have a society where people were freer, more gender-equal and had more agency over collective decisions than in the Dutch republic or other places van den Enden lived. Sadly, van den Enden met a gruesome end being tortured and hanged after he moved to France, when he tried to plot against Louis XIV.

Looking at the potential influence of Native philosophies on van den Enden is important, in part due to the clear influence of these ideas on Spinoza's Theological-Political Treatise (1670). Kort Verhael only had a small print run and was published anonymously. But the TTP was a bombshell book that scandalized nations, was quickly banned even in the Dutch republic (as this account by Nadler shows) and had a huge influence in Enlightenment political philosophy. And though Spinoza's account of democracy is somewhat different (sadly, as the final lines of the Political Treatise show he was no believer in gender equality), the basic idea is similar: in a well-organized democracy, we are equal, as we would be in the state of nature, but without having to fear others will harm or kill us, and so more truly free. Democratic deliberation allows us to reason together, to smoothen out individual quirks and weird ideas, and to come to better decision making.

—

* All translations from Dutch are mine. I could not get hold of an existing translation and went directly to the book as printed in 1662, which is available in the public domain (through Google Books). Apologies for inaccuracies etc.

Very nice, thanx for sharing! I'm studying the relation between Spinoza and Van den Enden (specially on radical democracy), and I'm also very interested in the sources of modern western thought that were ignored and erased later on. Marc Bedjaï sees Van den Enden's philosophy (and Spinoza's too) as part of the Hermetic tradition, which dates back to ancient Egypt (Kemet). Unfortunately, I could only access his "Franciscus Van Den Enden, maître spirituel de Spinoza". Cheers from Brazil, hope to keep in touch with your research!

I doubt I understand the 'presentism' debate (don't do history) and what I have read seems a bit reactionary --but it's puzzling why someone would think 'in the present we can see through racist ideology, we are capable of giving an account that is accurate enough because we are respectful & sympathetic to colonized people but IN THE PAST nobody had this capacity.

Why not? There were competing outlooks and ideologies then as well. Obviously, they don't quite have our methods and accountability for inaccuracy --but they were closer in time, and it's not as if people weren't curious and truth seeking in the past.

I don't really think this is the 'presentism' debate but the word fits. It's as if there's a sense of superiority of present people over past peopl.