On reading Iris Murdoch's The Sea, The sea and why kids these days can't read

Recent discourse has it that kids these days, even at elite colleges, don't read books anymore. They used to read one novel a week for a single course in English literature. Now they struggle to read a novel in the course of a whole semester, relying on AI summaries and cliff notes instead. Some students came to university having read only short stories and excerpts.

Good thing I am a 46-year old adult who has lots of time on my hands (since I am sick). I surely have no problem finishing a novel in a week.

Right. Right?

Unfortunately, what I found out was sobering and pushed me to self-reflection.

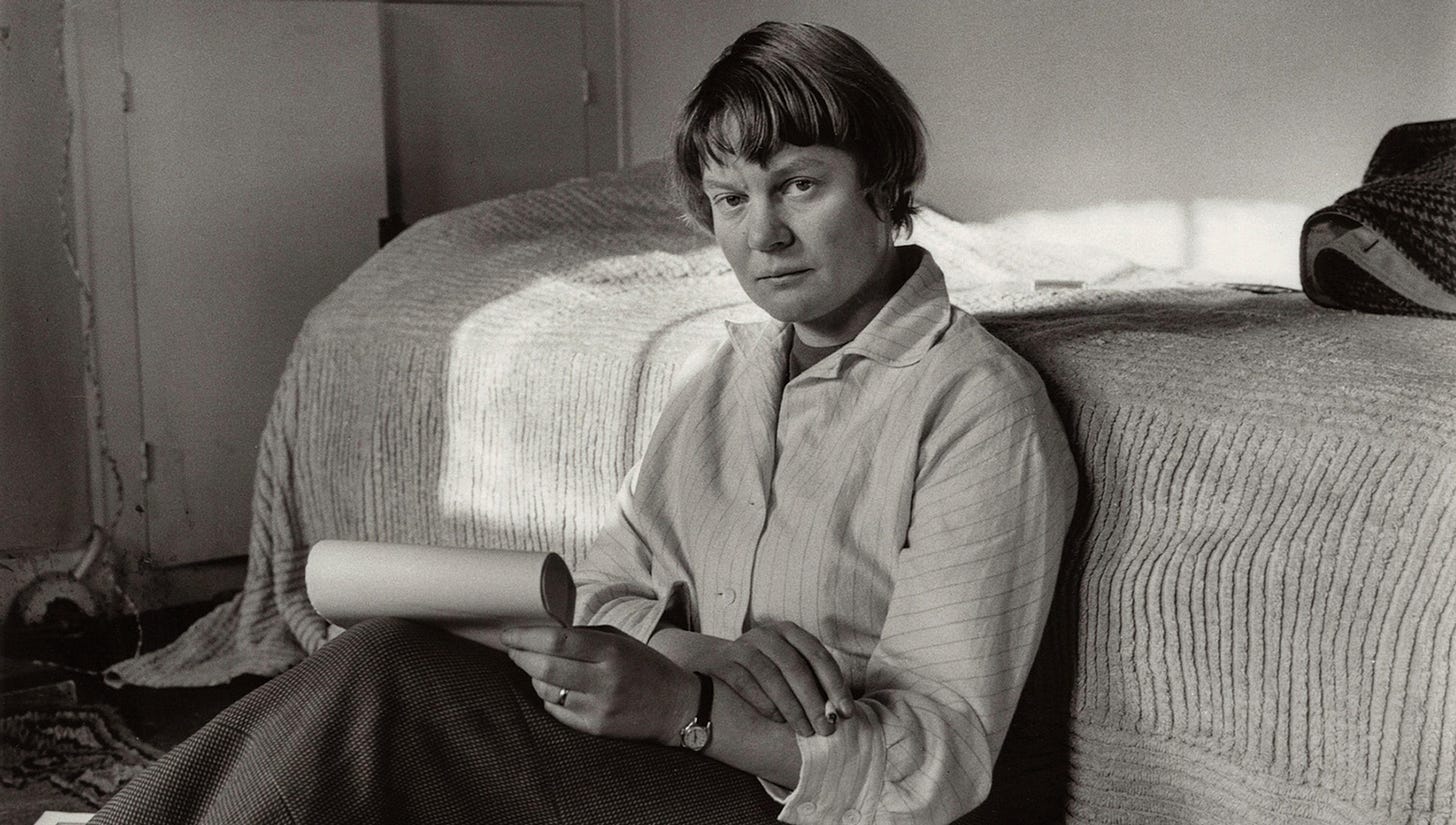

Context: a friend invited me to take part in an Iris Murdoch novel reading book club. I'm very excited about the prospect because I have never read an Iris Murdoch novel, and was looking forward to getting to know them. The plan is to read one novel a month.

We started out with her Booker Prize winning novel The Sea, the sea (1978). Before starting this novel, I imagined her work to be serious and ponderous, reflecting the existentialist influence in her work of people like Jean-Paul Sartre. This book does have an existentialist bent, but it is neither ponderous nor serious. Instead, it's a comedic romp that reminds one of Ex on the Beach, the British reality TV show where people's exes show up at various times at the coast.

But I digress.

I ordered The sea, the sea on Amazon two weeks ago. As I unpacked it, my first reaction was negative: wow, so thick. My second thought was: but surely, I have time for 490 pages of Iris Murdoch? I after all am not a Zoomer who can't stay off their phone. So I begin.

For background, it's been a while since I read any literary fiction. I used to read a lot of literary fiction in my twenties and even my early thirties. For example, I read one Thomas Hardy (Far from the Madding Crowd) and then went on to read them all, becoming ever more depressed as Hardy's characters go through their realist horrors of living (Tip: do not begin with Jude the Obscure or The Woodlanders; instead work your ways from mild pastoral such as Under the Greenwood Tree to more and more hardcore Darwinian realism. For me Tess of the D’Urbervilles was pretty close to what I could take). I read all of Jane Austen's novels, including the juvenilia, multiple times. Tolstoy's War and Peace is still one of my favorite novels with its endearing and wide-ranging cast of characters.

But then… I sort of stopped, so gradually that I didn't notice it. I cannot pinpoint the exact time when, but I know the reasons. Lack of time. I had two young children in my early thirties, was in constant stress on the job market moving from one postdoc to another. Writing philosophy papers and books became very time-consuming. I was already reading so much for work, I didn't want to read for pleasure. I read easily more than one book a week, but they were all philosophy books. When I tried to get back into fiction once I had more job security, I began to read short-form, especially genre fiction: science fiction, fantasy, and most recently, horror (I don't like this distinction between genre and literary, and I don't think genre is any less than literary, but it's convenient to use here). The result of this is a co-edited volume (with Johan De Smedt and

on short speculative fiction Philosophy through Science Fiction Stories.To get properly going with The Sea, the sea I had to set myself specific times to read: now do at least one hour, or let's read until lunchtime. I then realized (coming into this novel completely cold) that it is a comedy. There are serious and tragic moments, there are absurd moments (e.g., where the main character sees the sea monster, and others yet even more absurd I won't spoiler), but it is overall so funny.

The main character is Charles Arrowby, an un-self aware theater director in his early sixties who buys a house without electricity (Shruff End) at the British coast in order to write his memoirs in solitude. You quickly realize what an unreliable narrator he is, how full of himself he is (yet he remains somehow relatable and fun and interesting), and what a bizarre cook he is. His plan to sit in solitude completely goes off the rails as various people of his past come to visit him, or just happen to live there, with increasingly dismal consequences.

As I had reached the middle of the book, it became fun to read The Sea, the Sea and I had to put less effort in to commit myself to the book. But one thing became clear: my attention span, at least for fiction, is not what it was. What happened to 12-year-old me who lay in bed secretly reading with a torchlight, library book under the sheets so I sat in my own very small library?

It's not I think the phone (I should probably spend less time on social media, but I do not scroll on my phone). There's a deeper problem, which Robin Waldun, Youtuber and university student, highlights:

The problem with the focus crisis, in his view, is not so much that our attention spans have shortened. This can't be the whole answer because we are able to watch 2.5-hour Youtube videos explaining the scams of Caroline Calloway. So there must be another reason. For Waldun, that reason is that we do not ask enough “What is the value of reading these difficult novels?”

Now, one might say in response that there is endless discourse about the value of the humanities. Please, God, not another take on why the humanities matter! Let's unsubscribe from Wondering Freely. The discourse also always revolves around the same points: the humanities are intrinsically valuable, they help students to critically think, sometimes the motivation is nostalgia to an imagined period of Western greatness you see in some proponents of great books…

But all of this doesn't address concretely why students should read these books today. Why should, say, a 19-year-old enrolled in a 4-year liberal arts college read Jane Austen? Students don't listen to us, university professors, to learn the answer. The writing on the wall is everywhere: the budget for the humanities is slashed in most colleges I know, and departments of English, Philosophy, and History are closing. Small liberal arts colleges are in financial difficulty.

I realized, watching

's video, that I too have lost sight of why great literary novels are worth reading. I once knew it of course, and I read my Hardys and Austens with much pleasure. But over time, they had to make room for more pressing things. If you cannot afford mental space, a certain stretchiness in your day, then out of the window goes our capacity for wonder and discovery (so I argue in my book Wonderstruck).The problem is, you need to read to fully know it. Reading a lot gets you into a virtuous feedback loop where you want to read more. In the case of The sea, the sea, Murdoch said her book is about the triumph of virtue. You have this quite flawed main character who somehow, like Prospero in The Tempest (which clearly influenced this novel), finds peace with his past and with the people who dwell in his past. He realizes how you come to idealize and freeze in time people you met a long time ago (in particular, his first love Hartley). He abandons magical thinking, at least to some extent.

Charles Arrowby does not suddenly turn into a saint. He remains a silly person. But it is possible, even for him, to become more virtuous. To properly experience this, you need to read the novel. The long-form experience of a novel helps you to travel along in the messed up inner life of Charles and to see the difference between his reality and his imagination. Eventually, you as a reader can begin to question your own discrepancies too: what are people in my life really like? Because Murdoch is kind to her characters, and never stops making Arrowby relatable (even after all his bad decisions), you can become more kind to yourself too.

This payoff is hard to explain. You can say “Literary fiction helps us to grow as persons” but it doesn't quite hit the experiential dimension of going on a journey, with a set of characters, and to actually do the growing. I've found that many people who hardly read any fiction will have nonetheless some book they once read that did change their outlook and that they enjoyed. But somehow, it didn't push them to read more books.

Most of all, you can only experience this payoff if you let go of the utilitarian mindset. In a widely derided article, one Harvard student approached the problem quite well:

Indeed, in my experience, in most lecture courses where computers are permitted, students aren’t playing video games — they’re typically multi-tasking. They’re juggling some supernatural combination of passive listening and participation, note-taking, emailing, scheduling, p-setting, job hunting — maybe even eating….

It’s unabated hyper-productivity that got us here. And it’s the only way that many of us continue to excel in an environment that organically values achievement — constant, wide-ranging, achievement — above all else.

I would argue that even if the students are playing Candy Crush, even that is an expression of some the ever-busy lives we have. We just can't let go and be passive listeners, let a novel engulf you like the swirls of the sea in Murdoch's novel.

We must always be active and doing stuff. It has become worse over time. Productivity is a part of it, but not the whole story. We must be able to simply let ourselves be. We are often like Arrowby in The Sea the Sea, who tries to force the world, for example in trying to make his perfect (belated) instant family. Arrowby learns to let others be. The triumph of virtue is when he also learns to let himself be. I have yet to learn this lesson, but reading The Sea, the sea got me there part of the way.

Loved this! A good complement to your thoughts on fiction would be Le Guin’s short essay Some Thoughts on Narrative from 1980. I think you’ll enjoy it.

This is one of my favourite books, and its great philosophical seriousness to me lies with the fact that Arrowby takes himself and his adventures so very seriously.

*We* might be able to see how silly he is, in his desperate need to hold the centre in all surrounding stories (a theatre-director to the last!), but in some ways he remains at the end incapable of letting go of the belief that something momentous is always happening in his world. He might have set down one grand "plot" by the end, but his plotting nature remains. He will never truly see himself as we see him - just as we too are often caught fast by our own "plot armour" in life, unable to see how silly our own, relentless holding-of-the-centre also is.

Anyway, that to me makes this book an excellent pairing for your musing on literary types who, like Arrowby, act like those around them need to be "saved" from their mediocre (less literate) lives. There's an excellent argument to be made (and which is being made, by many) that we would do better to engage curiously with how the activity of "culture" is being enacted by this generation; and also, those of us who studied literary history know full well that today's moral panic has its own long history, too. How annoyed Nietzsche was with students who read pedestrian news rags instead of the Classics!

An education in the humanities can sometimes make silly theatre directors of us all: an insufferable demographic, really, when the sea of life rolls on, and we’re not ready for its indifference to us.