On playing Super Mario with your grandkids and why you should benefit yourself

The obituary case for ethical egoism

Political philosopher John Rawls has the image of a man who delights in just counting blades of grass—a stupid, useless pursuit that he loves but benefits no-one else. In a just society, should we let him? The grass counter question may apply to us too: is it okay to do academic philosophy investigating obscure questions if they're not very useful, while the world is burning and while we might turn our talent to more profitable and useful things to do?

Three things prompted me to think about this question.

First, the death of Daniel Dennett. Dennett's work on consciousness, free will, and religion was a formative influence for me, and the one time we met (I was a no-name postdoc at the time) he was very nice to me, so I remember him fondly.

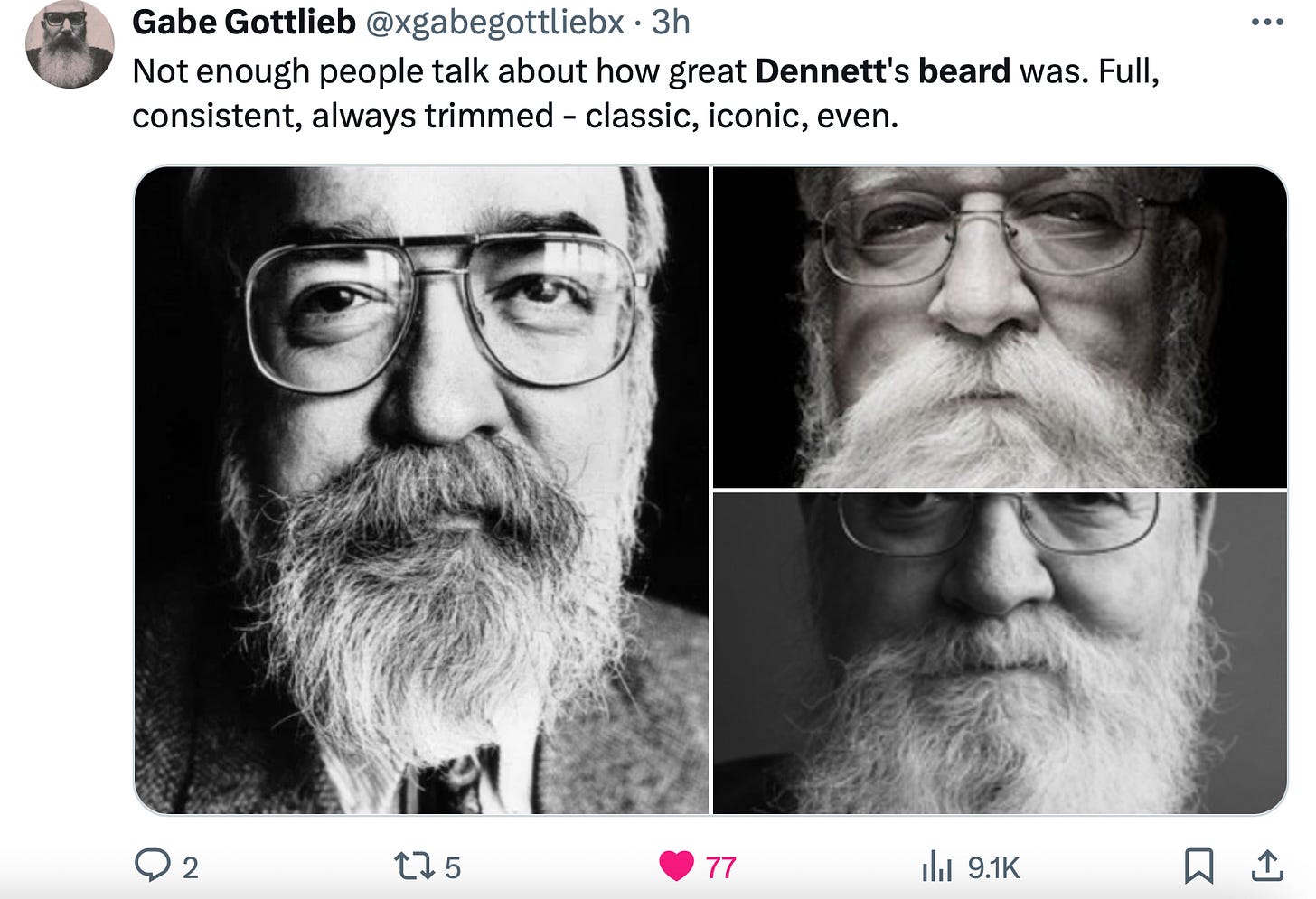

I was interested to see all these memorials of him on social media and elsewhere: People fondly reminiscing about him, and what made him so lovable—even down to his beard (see picture above). I'm going to go out on a limb and say from these testimonies that it appears Dennett was kind but not particularly self-sacrificial. He wasn't perfect—he had that smugness of the new atheists "Brights”, plus sadly he endorsed anti-trans activist writers, though he did it less stridently than e.g., Dawkins.

No, we love Dennett for how he helped us to think (few of us take over all his philosophical views, but they did help us to formulate our own). And he was simply himself, beard and all, his fun philosophical theories. This shows that—in spite of how messed up academia is—we aren't fungible tokens. Obviously few people reach his influence, reach etc. but it’s similar whenever I see memorials for less-well known scholars: we all leave our unique impact, on students, younger scholars, and our peers. It's wonderful.

This prompted me to think: is being yourself enough?

Shortly before Dennett's death was announced, I read an article by Nathan Robinson who wonders if we can really do academic philosophy in a time of crisis. Robinson looks to the effective altruist movement and Peter Singer's drowning child thought experiment to pump the intuition that we are really all wasting our time if we do academic philosophy. We should devote our time to improving the world.

Robinson worries Noam Chomsky may have wasted his time playing Super Mario with his grandkids when they were younger, seeing how much good Chomsky did in computer science and later in his activism.

Here's Chomsky on Super Mario in his own words

“What an utter waste of time!", some people might think. (Or you might think it makes Chomsky more endearing, as I do, imagining him as Luigi in a lake). As Robinson writes:

It’s easy to accept that Singer is onto something, that in the same way there is a duty to do something about people being hurt in front of us, there is a duty to do something about the pain of people we’ve never met. But then you have to ask: what does that duty require of us? Do we have to give up everything that isn’t reducing suffering? Would it be wrong for Chomsky to spend any of his time on linguistics, since all of that is more time he could be spending trying to stop wars? Chomsky occasionally liked to play Super Mario with his grandchildren when they were young. Was this time that should have been spent on political work?

Once you start thinking about all the “drowning children” (not just those who are drowning, but those who are being bombed, starved, abused, or getting sickened with preventable diseases), you can feel as if there’s a duty to become an ascetic, to spend all of your time trying to help. And some people do that. They truly limit their pleasures to a bare minimum and spend all of their lives trying to help others.

My intuitions don't seem to go the same way as Robinson's. Of course Chomsky should play Super Mario with his grandkids. To his heart's delight.

My grandma used to play a time-wasting board game with her grandkids called Game of Goose. Basically you roll dice and your little goose goes up the board, and you may find yourself in an inn, prison, the cemetery (you go back to square one) as you try to get to goose heaven. My grandma also did many good works, such as visiting the sick. Should she have visited more sick people and not played with her grandchildren? I don't think so. To play with your grandchildren is, or can be, part of a good human life. Obviously you should do it.

I worry that effective altruism and related utilitarian ethical theories reflect our relentless obsession with optimization and work ethic. It pours this obsession that we really should optimize everything into a plausible-sounding ethical theory.

This brings me to my third experience, namely, to witness what others value about me. You don't usually have people telling you this, or not often, but I was in a unique epistemic situation of being gravely ill (cancer) and choosing to be open about it too. Initially, it wasn't sure whether it was treatable and my outlook looked bleak. Now, it's not certain that I will fully recover, but more likely. So, many people told me what they appreciated about me. And while my service to the profession and the wider world was certainly part of it, the main thing that came back is that I play the lute (I play and I share videos on Twitter).

I found this intriguing because who am I benefiting, what problems am I solving, playing the lute? I am not even very good at it. Indeed, this is one reason I love playing the lute—nothing professionally hangs on it. So, how can playing the lute be part of a good life? How is it ethical?

Ethical egoism and self realization in Yang Zhu, Spinoza and Lorde

To think about why playing the lute is part of my ethical life, and to unify my observations about Daniel Dennett, Noam Chomsky playing Super Mario with his grandkids, and my lute playing, we need a different ethical framework.

That is the framework of ethical egoism, developed by such authors as Yang Zhu, Spinoza, and Audre Lorde. I've begun to outline a more detailed ethical egoist theory in recent work (here) and in a book that I hope to soon resume writing.

Ethical egoism is radically different from effective altruism and related philosophies, in that it says you should benefit yourself foremost. Yang Zhu (楊朱) was a Warring States philosopher, of whom no writings survive. Reconstructing his ideas from Mengzi and a few fragmented pre-Qin sources, one can surmise that he contributed to the ongoing discussion on human nature in pre-Qin philosophy in his development of a sophisticated ethical egoism (see Van Norden, 2007). Yang Zhu argued that Heaven had endowed humans with a natural inclination for self-preservation. From Mengzi and other authors we can see indirectly the formidable challenge Yang Zhu posed, and his enduring influence. Mengzi, ironically, also uses a child in danger (child at the well) thought experiment to argue against Yang Zhu: we don't have only selfish in inclinations.

Another famous ethical egoist is Spinoza (1632-1677), who has a clear formulation of this idea in his Ethics (4p18)

Since reason demands nothing contrary to nature, it demands that everyone love himself, seek his own advantage, what is really useful to him, want what will really lead man to a greater perfection, and absolutely, that everyone should strive to preserve his own being as far as he can.

Now importantly for Spinoza persevering in your being does not mean seeking out wealth, prestige, or hedonistic pleasure (see also his Emendation of the Intellect). For example, seeking prestige is an empty good that will enslave you, not liberate you. You might think prestige is something that will help you keep on top in a competitive world, thus something that helps you to persevere in your being. The problem with prestige is that you want what others want, namely the esteem of the people. You can lose their esteem, so you become anxious. All of a sudden you have to do a million things to uphold your reputation. You thus become less free. Also, prestige is what economists call a “zero-sum good”. If someone gains more, you will have less. As a result, you see yourself as in permanent competition with others, and you get a "monstrous lust of each to crush the other in any way possible" (p58Shol). So, this "love of esteem, or self-esteem, then, is really empty, because it is nothing." In a similar vein, money can enslave you. Obviously, you need some money to live, but it is possible, Spinoza holds, to "live contentedly with little.”

Spinoza sees us all as finite modes of God or nature, and to be ethically egoist, to play Super Mario or the lute, is then expressing a genuine feature of God or nature in all its glorious diversity and beauty.

Ethical egoism may seem like an easy philosophy, but it is difficult. It is hard to live such that you truly benefit yourself. I've found that out (to my chagrin, through tough experience) that I did in fact care too much about what others thought of me, working myself to death, overextending myself in a million committees and service tasks and other things for the profession just to prove to those whom I will never convince anyway that I'm really good enough to hold the position I hold.

Audre Lorde (1934 –1992) similarly has always been adamant that, as an activist against racism, parts of her identity that bring her joy are really just as important as the activism, including her poetry. She insisted she is not only Black, but also a lesbian, at the time that LGBTQ people were looked at with suspicion in anti-racist activist movements. But she insists that this part of her, as a “woman who loves women” is just as important.

In the epilogue to her cancer diary entries, she writes:

I had to examine, in my dreams as well as in my immune-function tests, the devastating effects of overextension. Overextending myself is not stretching myself. I had to accept how difficult it is to monitor the difference. Necessary for me as cutting down on sugar. Crucial. Physically. Psychically. Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.—Lorde, A Burst of Light.

Self-preservation is important. So, I'm going to say no a lot going forward. If the profession requires that I continuously overextend myself to the point of serious illness or death, it's probably better that I let it fall apart a bit. We need to take care of ourselves, do things that bring us and others joy.

The obituary case for ethical egoism

Months ago, someone at work died (let's call him “Nick"). I'm going to keep details vague about this person to protect privacy. Nick was a very shy, private person and we didn't know him that well in spite of working alongside him. Our head asked if we wanted to share some things Nick and we were all sitting there in silence, still shocked at his sudden death.

Until a colleague spoke up. “He liked cars.”

That broke the mood. Relief flooded through the tense atmosphere. “Oh yes how he liked cars.” We shared memories of his cars, and the ones he liked best. Now, liking cars does not fit in what Brooks calls the “resumé virtues", the things that look good on a CV. But it doesn't fit in his description of “eulogy virtues” either. For Brooks, the eulogy virtues are “the ones that are talked about at your funeral — whether you were kind, brave, honest or faithful. Were you capable of deep love?”

Well, obviously, don't be a horrible person, but often at eulogies we talk about people's unique quirks, likes and dislikes, what made them really them. Nick's cars. Often at memorials or in obituaries we mention that someone was a big fan of a sports team. Ethical egoism indicates why being a fan of the St Louis Cardinals (for instance) is virtuous. It is virtuous because doing so, you delight in something, you benefit yourself, and you are a unique expression of nature.

I'm well aware that this sprawling text did not offer a definite argument against the effective altruist and related philosophical ideas that we should maximize the good we do on our time here on earth by trying to find, identify all those drowning children and then finding the means (like making a lot of money and donating it to effective charities) to help them to the best extent we can. But the obituary case, and my observations above, should at the very least give us pause about this efficiency maximizing impulse and to believe that Rawls's grasscounter really should be able to count grass, to his heart's content.

I agree with Richard that ethical egoism, typically understood, can readily allow (and even require!) harming others in ways that you don't want to allow, so a better name for your view would be better.

I think Nathan Robinson's complaint is misplaced and unfair: why, among all the many frivolous, wasteful, and actively harmful things that many people, fields and professions people engage in, is philosophy singled out as some kind of waste of time or distraction? Really??

This is beautifully written. At first, I was thrown off by the endorsement of "ethical egoism." Consideration for others is the cornerstone of ethics and "ethical egoism" suggests prioritizing self. Egoism traditionally fails to recognize or prioritize our interconnectedness. But this argument that self-interest *must* involve interconnectedness is a great one.

Chomsky made the right choice because when we love another, we share their space and share their joy. Nothing matters more than this immediate moment and this small, shared space and Chomsky intuitively recognized that. Spending time, simply being present and available for his grandchildren was the very opposite of wasted time. I cannot imagine a solid ethical argument to the contrary. I don't know what to call this expansive conception of self and self-interest but whatever its name, it is beautiful and true.