On letting yourself be

How the impossible schedule of Eric Satie, the eccentric French composer, can help us to simply let ourselves be

Did you know you could increase your productivity if you dream lucidly and write code in your sleep? Imagine the productivity gains! Why would you while away the time in bed, about a third of your life, when you could be creating value for your employer, or for yourself?

Okay, let's start again.

An artist must regulate his life.

Thus begins Eric Satie's absurd and unrealistic schedule for this day. Let's see what we can learn from this thought experiment.

Satie's infamous schedule is up there with Kant's walking regime and Ursula Le Guin's writing schedule, but as we'll see there's something a bit different about it. It goes like this:

Memoirs of an amnesiac. The day of a musician.

An artist must regulate his life.

Here is a timetable of my daily acts. I rise at 7.18; am inspired from 10.23 to 11.47. I lunch at 12.11 and leave the table at 12.14. A healthy ride on horse-back round my domain follows from 1.19 pm to 2.53 pm. Another bout of inspiration from 3.12 to 4.7 pm. From 5 to 6.47 pm various occupations (fencing, reflection, immobility, visits, contemplation, dexterity, swimming, etc.)

Dinner is served at 7.16 and finished at 7.20 pm. From 8.9 to 9.59 pm symphonic readings (out loud). I go to bed regularly at 10.37 pm. Once a week (on Tuesdays) I awake with a start at 3.14 am.

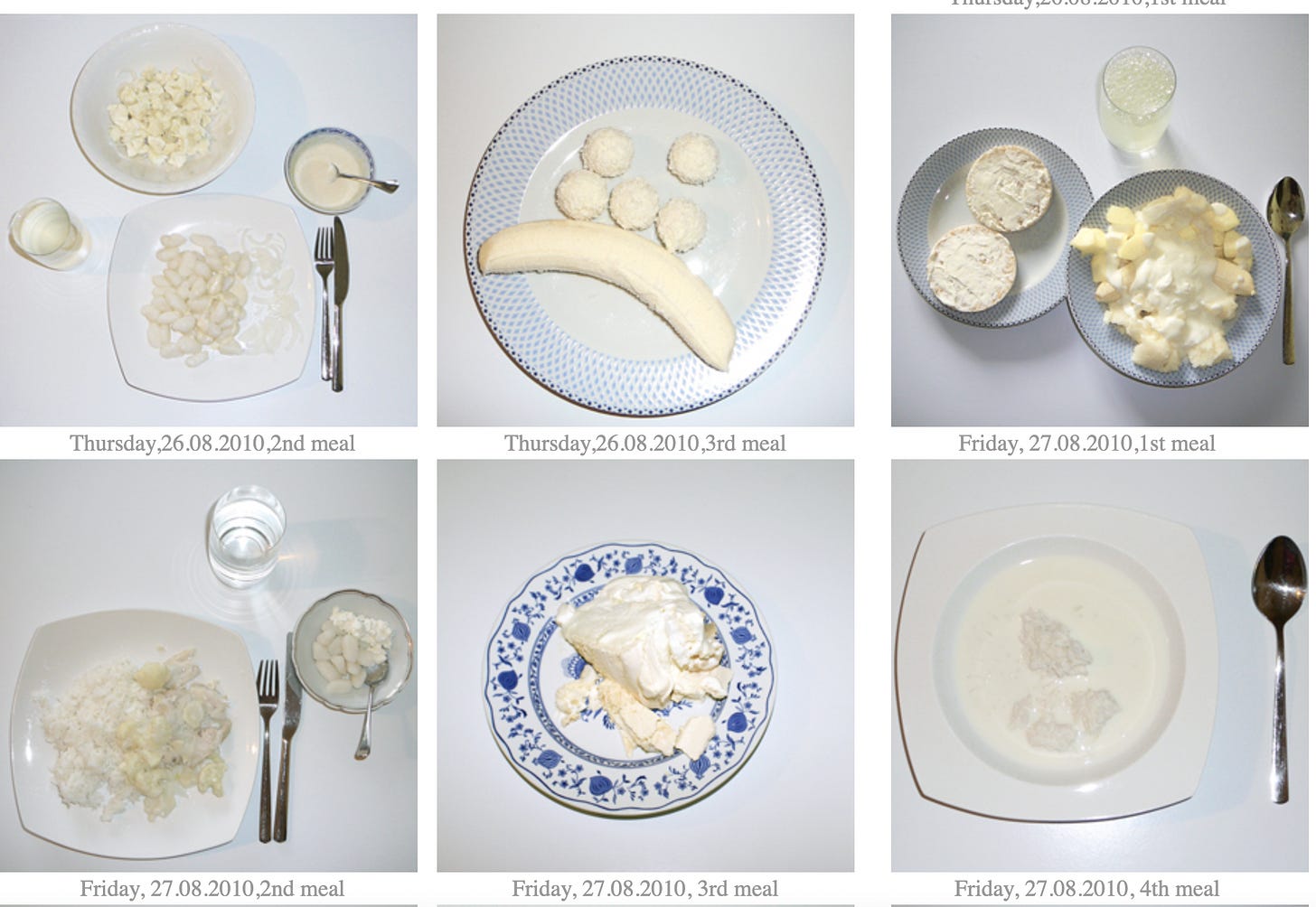

My only nourishment consists of food that is white: eggs, sugar, shredded bones, the fat of dead animals, veal, salt, coco-nuts, chicken cooked in white water, moldy fruit, rice, turnips, sausages in camphor, pastry, cheese (white varieties), cotton salad, and certain kinds of fish (without their skin). I boil my wine and drink it cold mixed with the juice of the Fuschia. I have a good appetite but never talk when eating for fear of strangling myself.

I breathe carefully (a little at a time) and dance very rarely. When walking I hold my ribs and look steadily behind me.My expression is very serious; when I laugh it is unintentional, and I always apologize very politely.

I sleep with only one eye closed, very profoundly. My bed is round with a hole in it for my head to go through. Every hour a servant takes my temperature and gives me another.

Satie's schedule is not real

This schedule is often quoted as a serious account of Satie's life routines, but it's clearly meant as satire. Though Satie was an eminent composer (of such works as the Gymnopédies), he lived in squalor in a tiny, very messy one-bedroom apartment for most of his life, with two grand pianos standing atop each other, and he never invited anyone in. So he didn't have a horse, a domain, or a servant. Alluring as it sounds, he did not only eat white foods. And Satie was known for weird ideas, such as writing three pieces in the shape of a pear.

Still, it's interesting to try to follow the schedule, so composer and pianist Nahre Sol gave it a shot, including the bizarre super-short slots for lunch (from 12:11 to 12:14) and dinner (7:16 to 7:20 PM). However, she did not sleep with one eye open and there was no servant taking her temperature hourly.

As she mentions, in spite of the pointlessness of it, doing this exercise ended up being inspiring, “I learned a lot about myself and about what productivity means … Productivity is really pushed onto us. The schedule has a lot of space, where you can get bored.”

It made me think about creating space to simply let yourself be. My middle schooler unfortunately is in a school where they don't even have recess at lunch, just a mere 25 minutes at noon, and they go from classroom to classroom regimented by the clock (3 minutes to get from from one room to another). There is no time to let them be, but when I complain as a parent I am told about learning goals and about the importance of not letting time go to waste. Parents further help to clutter this busy schedule by clubs and after-school activities. This is all (as Foucault would say) preparation to make kids into docile bodies that are used to live by other people's schedules and do their bidding.

By the time we grow up, we have internalized this so much that we have internalized the injunction not to waste time.

How can we think of the importance of emptiness, leisure, free play, letting ourselves truly be? Satie's schedule gives us an imaginative clue. I love how he's inspired from 10.23 to 11.47. I love there's gaps in the schedule where nothing is noted and that you can fill in as you wish.

I've been thinking about the topic of giving ourselves breathing space these past years. It's a key theme in my forthcoming book on wonder, Wonderstruck: How awe and Wonder Shape the Way we Think (Princeton University Press, 2024). And I have several shorter works on related topics. For instance in this piece for Psyche (coauthored with Pauline Lee), we take inspiration from the Zhuangzi on not seeing yourself as an means to some instrumental goal but to wonder freely. In this piece for Aeon, I take Næss and Spinoza as inspirations for the idea of radical self-realization.

One other way I've been thinking about giving yourself space is that it is a virtue: the virtue of letting be.

The virtue of letting be

As Kym Maclaren explains in a beautiful paper on Maurice Merleau-Ponty and intercorporeality, we should cultivate the virtue of letting others be. We should let others be in their radical otherness that we encounter while bodily engaging with them. It doesn't come naturally. Maclaren gives the example of a horse trainer who trains and trains a horse, reducing it to its money making potential, never allowing it to simply wander freely and be a horse. The training fails. The horse becomes sullen, then breaks down.

We shake our heads at the horse trainer, but we often even treat ourselves this way, sometimes even more harshly. As milk cows that require a steady flow of productivity. Consistency is key! The problem is, as

points out, that this does not give you enough space to mentally recharge.Maclaren talks about letting others be, which if it succeeds is not a mere intellectual achievement. It is also a corporeal achievement, where we resist to physically dominate—instead we try to engage with others in ways that are open, inviting, and playful rather than deterministic, like the horse trainer who gives the horse a break and allows it to rest and roam freely. While her paper is about letting others be, you can also liberate yourself in this way. Liberating ourselves from the morality of customs—as Nietzsche would have it in Dawn—in our case, from the abstract ideals of productivity for its own sake and the good of the economy, we can also begin to think how to liberate ourselves from the oppression of others.

Freedom would be complete if, for instance, Amazon workers could get adequate bathroom breaks, but it is important that we can to the extent possible also liberate ourselves from this stifling mindset .

Letting be can also sometimes fail, which is why it is important to try out bodily routines and playful ideas as the one offered by Satie. Precisely because it is so absurd and yet so capacious, it is something that can push us out of our comfort zone so completely that we can be prepared to lose the productivity mindset that has absolute dominion over us.

If you can't let go of the productivity mindset, try a weird routine. Or eating only white food. For a little while.

I'm curious how your idea of letting be corresponds to what I've called the "negative virtue" of "Gelassenheit" in medieval Rhineland mysticism. I think there are definitely parallels, though clearly the kind of detachment and "letting-go-ness" of an Eckhart or a Suso is less a recipe for psychological health and more the first step toward divine illumination and union. (Not that it can't be used in the former way in a more contemporary context...)

Helen, I cannot wait to read your book! It has so much resonance with my own writing. I have started demystifying myself of the "internalized the injunction not to waste time" and it really has opened up deeper understanding of how I operate.