Museums, elitism and activism

Why you should never, no matter how good the cause, throw soup at a masterpiece

Earlier today, two protesters approached the Mona Lisa and splattered it with pumpkin soup. This follows a new trend of drawing attention to one's cause by vandalizing, or at least attempting to vandalize, artworks with significant common heritage value.

The activists weren't climate activists, but rather were protesting against food insecurity.

Still, a lot of news media outlets reported that "climate activists” aggressed the Mona Lisa, probably because of earlier actions such as the attack on Van Gogh's Sunflowers in the National Gallery of London. And prior to this, climate activists would glue themselves to masterpieces.

Attacking artworks is not a good strategy.

It has never been a good strategy, even when it was novel. I find these actions profoundly alienating and infuriating, and I wish climate and other activists would stop doing it. It seems to me that activism that alienates a lot of potential constituents is not a good way to go.

Here are reasons why you should never throw soup at a masterpiece.

Risks to the artworks

A common defense I see is of these actions is, “They're safe behind glass.” This indicates the protesters don't realize (or they do and they don't care) how delicate artworks are. There's a reason we don't routinely throw soup or purée at paintings, and that is because they are fragile and precious. During my studies as an undergraduate art major, we learned about conservation and about how exposing works to the public has upsides, namely the public gets to interact with these awesome works in real, and get the unforgettable phenomenological experience that photos and websites can't give you. But these always have to be balanced against downsides, namely risks of damage. Even simply sustained sunlight or flashlight can alter the chemical composition of the paints. Conservation is a complex art fraught with compromises.

There is another risk: artworks that are targeted by well-meaning activists will lead to museums taking action, introducing ever bigger barriers (plexiglas, distancing) between the public and the artworks. This risks to limit their ability to fully appreciate these masterpieces on location.

Art and the planet are not in a zero-sum game

Climate and other activists present art and the planet as being in some sort of perverse zero-sum game. Oh, as you care about Leonardo da Vinci but not about the rainforest? Well I will make you care! I'll pretend to destroy your precious paintings!

So for example, here's an interview with two Just Stop Oil activists on why they threw soup on Van Gogh's Sunflowers

Because of its notoriety. And it's a beautiful work of art and I think a lot of people, when they saw us, had feelings of shock or horror or outrage because they saw something beautiful and valuable and they thought it was being damaged or destroyed. But, you know, where is that emotional response when it's our planet and our people that are being destroyed.

It is strange to use artworks as the target. They are luxuries in the sense that they do not directly relate to our everyday survival. But as luxuries go, they're remarkably sustainable. Many masterpieces that are targets of these campaigns were painted by people who had modest lifestyles, such as Vincent Van Gogh, who had to be financially helped by his brother because he was not able to make a living with his art. A wealthier man, such as Leonardo da Vinci, had a tiny carbon footprint compared to most of us today. Most present-day visual artists, even ones who do well and sell works at good prices, do not have extravagant lifestyles.

Compare the production of these artworks, and even their whole present ecology with museums and galleries with other luxuries, such as yachts and it's clear paintings are more sustainable. Compare them to NFTs (what was the point of these again?) which have considerable carbon footprint, and it's so bizarre that climate activists would single out paintings. A painting can sit for centuries in someone’s attic without being noticed and then suddenly discovered. So art is a sustainable pleasure we should encourage and cherish, not present in some sort of zero-sum game.

Art helps us to become sensitive again

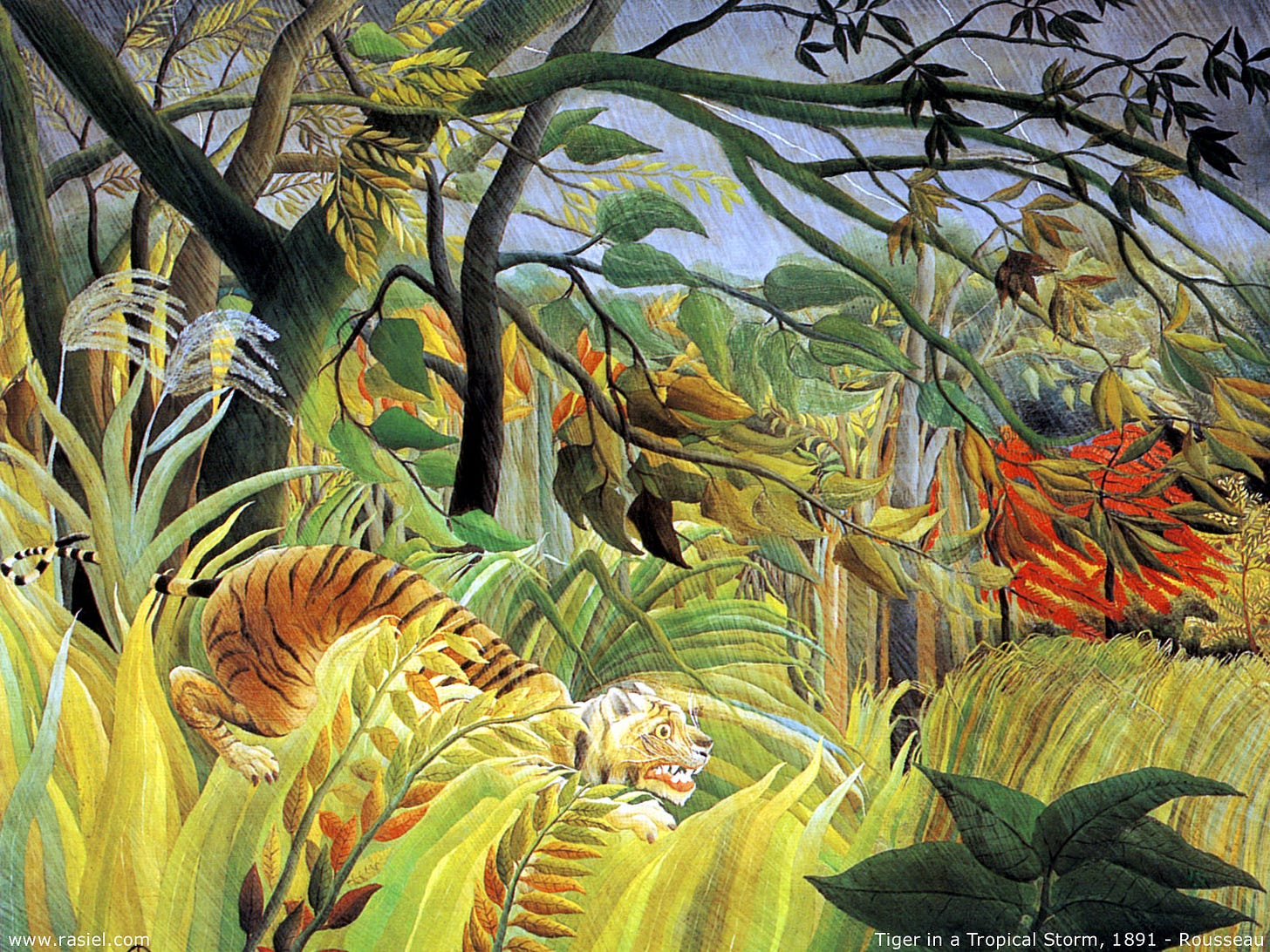

Art appreciation helps us to become sensitive again to our world and its beauty. Looking at art helps to combat numbness and despair. Look at a painting such as Surprise and you might feel with the painter how awesome a tiger in a forest looks, and how awesome wild animals and nature are. Something that is worth preserving. Even art that is not directly related to the natural world might awaken something within the viewer and help us to cultivate a sensitivity to the world.

Numbness and despair are key reasons for why people are unable to shift the dial on climate. The situation looks so dire that we simply look away. How is vandalizing artworks supposed to help with this?

The argument is “At least it gets us to talk about climate change,” but we are already talking. Awareness is not the issue. In many countries, the public is aware climate change is happening, and worry about it. But the narrative has cleverly shifted to “any cure will be worse than the disease” and “it's too late already.” It's unclear how throwing soup at masterpieces is going to change that.

Another common objection is “They will always object to our activism no matter what!” This is probably true. Your activism will disrupt and inconvenience people, but that is no excuse for simply doing anything. Activism is hard. Drawing attention is just one factor . Thinking about what works and getting people on your side is another, equally important factor. Don't be defeatist about it at the outset! Trying to get a broad constituency on your side matters.

Optics unfortunately do matter, they are an intrinsic campaign of activism. So one needs to carefully consider how to rally people to your cause, in balancing urgency with the outlook of hope. Obviously, you cannot control how Fox News will report on you, but you can control your actions, and vandalizing paintings just isn't the thing that wins hearts and minds.

Art in museums is not elitist, but of the people

When I discuss this topic of vandalizing artworks for your climate activism, I often hear the mystifying “Art in museums is just for the elites anyway.”

It is bizarre, to say the least, since museum art is the opposite of elitism. I grew up in a one-income blue collar household and going to museums was a thing I could do because it was inexpensive or free, unlike say, visiting a theme park (not the sort of thing people call elitist), which was expensive and far away.

Museums in their modern form started during the Enlightenment era in Britain and other countries as places where the common people could see artworks and artifacts, as well as objects concerning natural history, to help educate them and thus to liberate them.

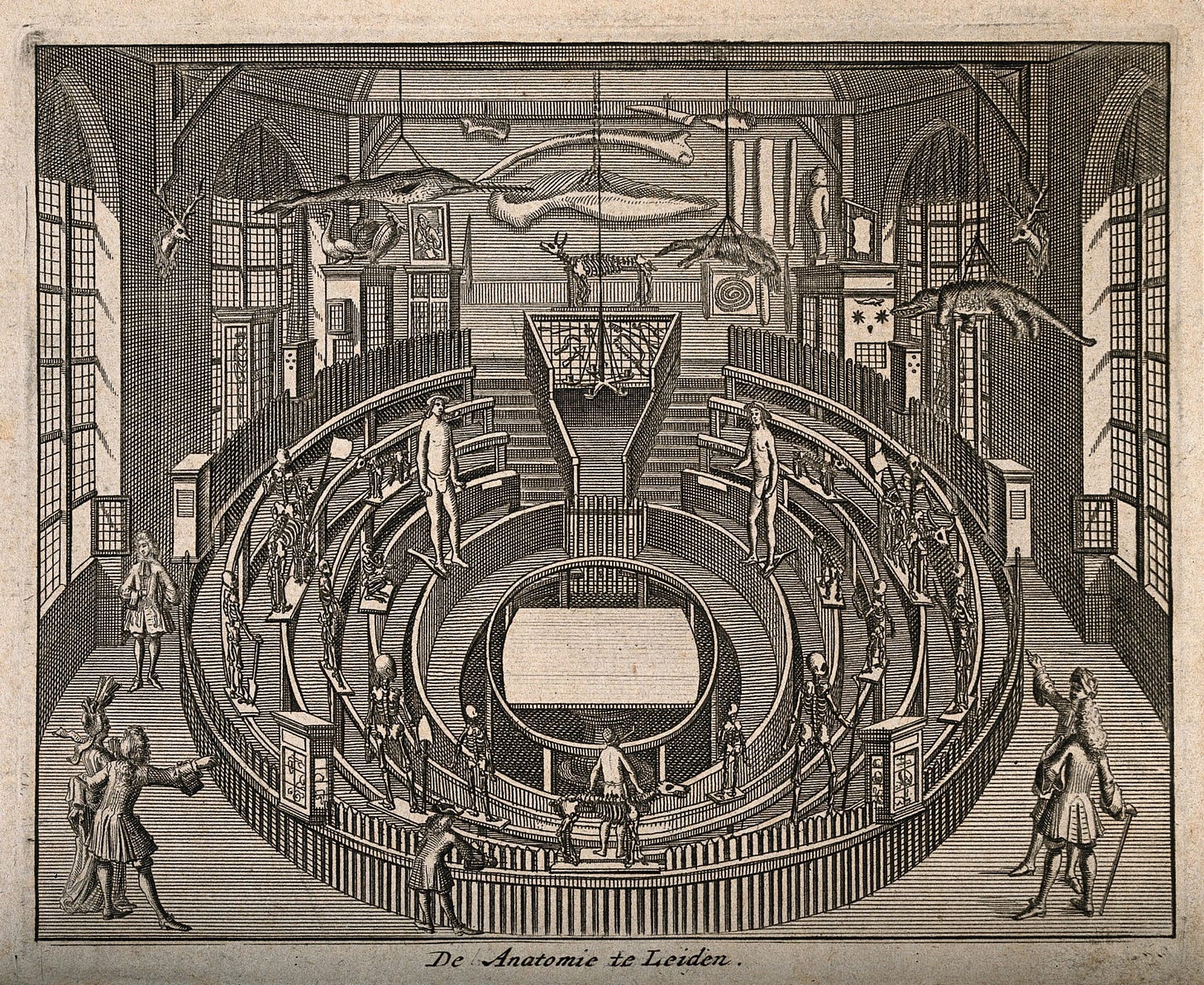

It is amazing, if you consider it, that many of the artworks you can see in places like the Louvre or the Metropolitan Museum, were originally owned by wealthy people and displayed in their private estates. They were only to be enjoyed by these super-wealthy people, their immediate family and descendants, and people in their immediate circle. Museums grew out of cabinets of curiosity, that were first privately owned, then also owned by universities and other learned institutions such as the Leiden Anatomie-Hal (see below.)

Then you had, in the late 17th century, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford as the first publicly accessible museum, and the British Museum, which was made in the 18th century by merging several private collections, so that British people could enjoy these wonders and be educated.

You need to be a bit lucky to live near a good museum. Even so, many people do. For example, Saint Louis Art Museum is a local museum in not a huge city like Chicago or New York City, but it is still a wonderful museum with a fantastic collection of African art and Asian art, and decent collections of ancient Roman, Medieval and early modern artworks, among others.

Public museums were created in the same period that public libraries were created: to emancipate and educate the people, often free of charge.

Even if not free of charge, visiting a world-class museum is far less expensive than, say, visiting Disneyland and you can experience wonders and marvels in a museum that seem more profound than a rollercoaster ride. You don't even need background knowledge, as there is no one right way to respond to artworks, and you can respond to them and evaluate them however you like, based on your purely personal appreciation.

In sum, there is no justification for vandalizing or threatening artworks to advance climate activism goals.

This kinda makes sense, but I have a couple of comments.

First, you misread the quote. You say they make it a zero-sum game, but that's not what the quote says. It says they're using the outrage that we feel at the destruction of beautiful art to remind us of the outrage we *should* feel at the destruction of the beautiful planet. That's a different mechanism, not connected with zero sum.

Second, I find it hard to endorse arguments like this, because they can be made for every form of protest. The protesters who block roads are delaying poor commuters with nothing to do with the crisis - therefore roadblocks are wrong. Strikers who shut down factories are harming consumers who didn't have anything to do with the low wages - therefore strikes are wrong. There's *always* a reason to say a protest is bad. That's the nature of protesting!

What I don't think you've done successfully here is to show that the art protests are worse than other forms of protest; or that they're unnecessary. Which is not to say that you're wrong. But I don't think these arguments add up to enough.

Very salient article! I'm always shocked when this happens because most of us going to museums and appreciating art actually support climate change and social causes...

Museums in general have been a hot topic where I am though - I'm super curious your take on things like this, which causes a lot of outrage here: https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-68066877