Letters on evil (Part 1)

Intentions of friendship, difficult to digest opinions, and frustrations in the Spinoza-Van Blijenbergh correspondence

In the winter of 1664, the grain merchant Willem Van Blijenbergh began a correspondence with Benedict de Spinoza that would last a total of eight letters. It starts with earnest intentions to form a philosophical friendship, and it ends with a rather abrupt final letter by Spinoza asking Van Blijenbergh to stop writing to him. Purely on a psychological level, the letters are very interesting.

Van Blijenbergh did not know Spinoza personally, but he had read his commentary on Descartes's Principles (published in 1663) in Dutch translation. This is Spinoza's only work to appear under his name in his lifetime or shortly thereafter.

The consensus among a lot of Spinoza scholars is that Van Blijenbergh is not very bright and that the correspondence is not that illuminating. For instance, Curley writes in his collected translations (Preface), “Van Blijenbergh is a tedious fellow, obscure, repetitious, and slow to see the point. His doctrine that Scripture must be the ultimate authority (IV/96-98) is not a very promising basis for discussion with Spinoza. But he is not an utter fool.”

It is true that Van Blijenbergh's letters are tedious and repetitious. This is why, when I read the collected works, I skimmed over them, and over Spinoza's replies.

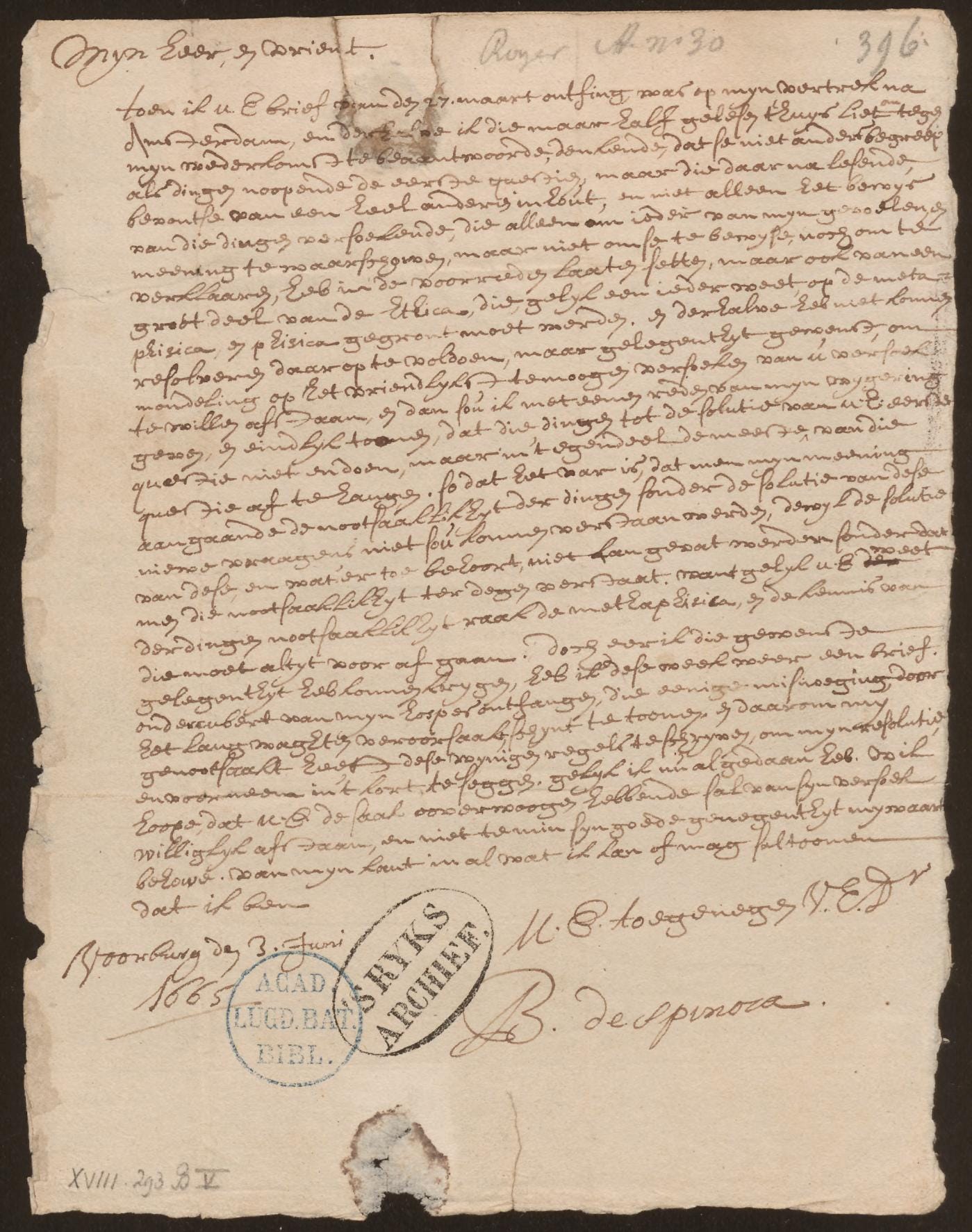

However, I kept a residual interest. Like (alas) Van Blijenbergh my Latin is simply not good enough to read letters fluently in the original. Most of Spinoza's letters are in Latin, but his letters to Van Blijenbergh are originally in Dutch. Dutch is my first language, so I can read it fluently. We even have autographs of some of these letters! You can see samples here and I put twp examples below. Here's Spinoza's final letter to Van Blijenbergh:

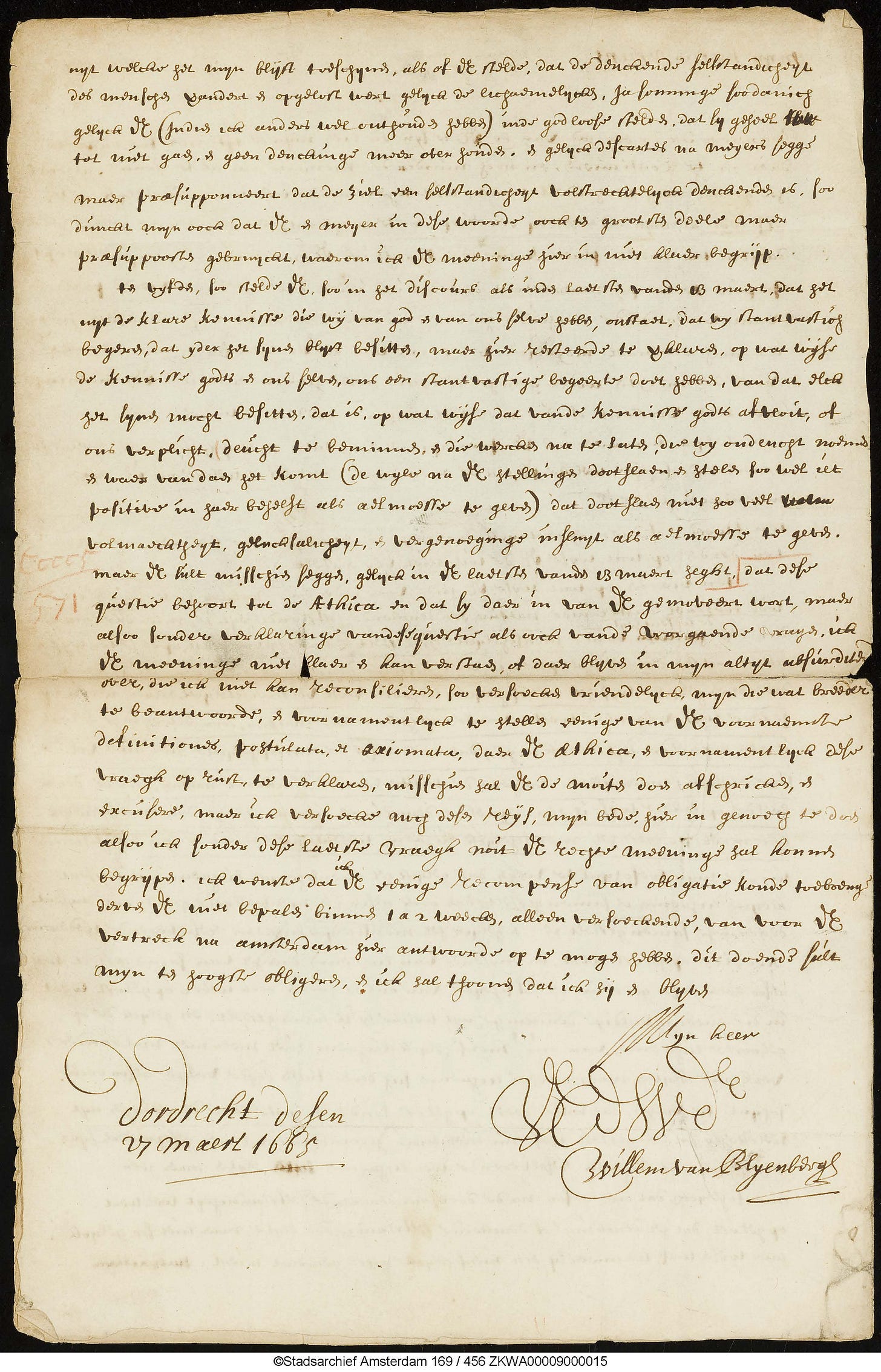

And here's the final page of one of Van Blijenbergh's letters to Spinoza:

Purely from a paleography perspective, these letters are fascinating. Even the way these authors write, down to the different way their quills were sharpened is intriguing.

I read Deleuze's Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, where Deleuze prompts us (in chapter 3) to take another look at these letters. Deleuze thinks that Van Blijenbergh's continued questioning helps us to end up with the clearest formulations of what Spinoza understands by “evil.”

So, when my sister sent me the book “Brieven over het kwaad” translated and edited by Miriam van Reijen, I decided to give the letters a second, more thorough look, and to read them in Dutch, as they were originally written.

Van Reijen, like Deleuze, doesn't think Van Blijenbergh is dense. Rather than misunderstanding, he finds some of Spinoza's thoughts “hard to digest” (“moeilijk te verteren”). The letters are about a perennial problem in philosophy of religion: evil happens, God is supposedly omnibenevolent. Why does evil happen?

We get a dilemma, as Van Blijenbergh stipulates: Either God caused Adam to sin (at the time this was the received story of why there is death, suffering, etc in the world) and then God is the author of evil. Or God did not cause Adam to sin (the Augustinian picture) but that seems incompatible with Spinoza's views.

I put a summary of the letters, retold in my own words, below for your amusement. Here's the first pair of letters. More to follow!

Letter 1, Van Blijenbergh to Spinoza, Dec 12, 1664, Dordrecht

Good sir and unknown friend,

I really enjoyed your commentary on Descartes’s Principles! It really got me thinking. I'm a grain merchant, but I'm not interested in profit. What interests me rather is the pursuit of truth. So, that's why I've been so impertinent to write to you, because I see in you a fellow seeker of truth. As I've said I adored your work. However, there were some things in it that lay a bit heavy on my stomach.

First, I wanted to see you in person, but I've been so busy with my work and then there was the plague, that I had no intention of catching, so I decided to write to you. Anyways, as I was saying, I don't want this letter to be just empty praise of your delightful work. So here's my question: You say God didn't just cause everything to exist, but continues to determine their movements. If that's so, then either there's no evil in these movements, or God directly causes evil movements.

Take Adam: if his will to eat from the forbidden fruit was caused by God, then God seems to cause what we call evil. It doesn't seem to me that either you or Mr Descartes can solve this dilemma! If God causes both the actions of the good man and the evil man, then we get the dilemma that either: the evil actions aren't evil, or God is responsible for evil.

So here I've put something that I cannot accept in your treatise. I'm an honest man who makes an honest living. I'm only concerned for the truth. I would be very grateful if you could send me a reply, which I would enjoy a lot.

Your devoted servant,

WvB.

Letter 2, Spinoza to Van Blijenbergh, January 5, 1665, Schiedam

Sir and very agreeable friend,

I understood from your letter your great love of truth. Because of this, I not only will grant your request but I'll also do all I can to get to know you better and to become friends. Nothing pleases me more than to become friends with people who love truth, because that friendship is based on a mutual desire to know the truth.

Okay, so on to the question on evil. One problem is: you haven't defined what you mean by evil. I don't think evil is factual, or that sin is factual. We cannot do anything that goes against God's will [which is what sin means]. Nor can we make God angry.

Let's look at Adam eating the fruit. To be perfect is to do what is in one's nature. When we see bees at war, or pigeons being jealous, we don't mind that in animals, we say, it's in their nature. In fact, those things make us wonder and feel delight at them more. Similarly, Adam's action was caused by God. Now, from Adam's perspective it seems like he's missing out—he will lose his state of perfection [Garden of Eden] and go to a state of lesser perfection [having to toil for food etc]. But that's only from his perspective. It's not objective. From the perspective of our minds, he is being deprived, but not from the perspective of God's mind.

You might wonder :Why then do the scriptures say we should be pious? Scriptures give a distorted picture of God as anthropomorphic, who can get sad or angry. That's because scripture is accommodated to the minds and limited understanding of common people. God isn't like that.

Now I do think there are gradations of perfection—something is more perfect the more it is real. So both the infidels and the pious people serve God. But while the pious people become more perfect in doing so, the infidels get less perfect, like a tool that's being used in the hands of a workman and that gets more and more worn out in the process.

I'm sorry for my clunky Dutch, I wish I could write to you in the language I have been brought up in. But it'll have to do for now.

Your devoted friend and servant,

B. de Spinoza.

The casual mention of the plague in Van Blijenbergh’s letter made me laugh for some reason. Thank you for this post — so interesting! Excited to read the upcoming posts.

This is very nice!

I'm working on Hume on Liberty and Necessity, and this argument - or something like it - comes up in Enquiry 8 as a response to his compatibilist position. He writes (check actual sources for italics, etc.):

"It may be said, for instance, that, if voluntary actions be subjected to the same laws of necessity with the operations of matter, there is a continued chain of necessary causes, pre-ordained and pre-determined, reaching from the original cause of all, to every single volition of every human creature. No contingency any where in the universe; no indifference; no liberty. While we act, we are, at the same time, acted upon. The ultimate Author of all our volitions is the Creator of the world …" (E 8.32)

One formal point that interests me about the passage is within the broader argument about the ultimate Author is the consequence argument for incompatibilism: ".... there is a continued chain of necessary causes ...." It goes without notice but Hume replies to the argument for incompatibilism by first expanding it into an argument with a broader, more unacceptable conclusion, and then responding to the broader argument. He never responds to the consequence argument directly, but this is the section about Liberty and Necessity.

You should check out the passages. Hume also says there are two parts to this objection:

"First, that, if human actions can be traced up, by a necessary chain, to the Deity, they can never be criminal; on account of the infinite perfection of that Being, from whom they are derived, and who can intend nothing but what is altogether good and laudable. ... Secondly, if they be criminal, we must retract the attribute of perfection, which we ascribe to the Deity, and must acknowledge him to be the ultimate author of guilt and moral turpitude in all his creatures." (E 8.33)

Quotes from davidhume.org