Letter to Robin Waldun, on reviving the early modern tradition of philosophical letter writing

To the Esteemed and Perceptive Eternal Student

I'm writing this elaborate salutation to be in the style of the letters I am about to discuss, philosophical letters by authors of the early modern period (roughly 1500-1800) by authors such as Sophie de Condorcet (pictured above, née Sophie de Grouchy), Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia, Henry Oldenburg and Baruch Spinoza.

When you mentioned on your Substack chat that you intend to revive the humanistic letter, I became excited at the prospect, and I aim to offer in this letter some ideas about how we might revive this practice.

Some quick preliminaries: We do not (yet) know each other personally. I've enjoyed your Youtube channel about how to read difficult books such as Heidegger's Time and Being, as in the video below.

I am a philosophy professor at Saint Louis University, and always looking for new ways to get my students to read the material I give them to read, so your channel captured my interest. I know that many people, including viewers of your channel, want to read the classics. So, it is a matter of clearing obstacles in their way.

One such obstacle is simply fear: people are told over and over how difficult these past authors are, and that they need a ton of interpretative material to begin to understand them. And so they watch videos of people talking about the classics, including such figures like Jordan Peterson whose grasp of philosophy is shaky at best. These viewers watch long video essays about Heidegger, Tolstoy or George Eliot when they could be reading these authors first-hand!

This is a great pity. I prefer what one might call an evangelical approach to the classics: people should read them directly rather than get stuck in a morass of interpretive layers. Don't worry too much about reading them right (you can always read secondary literature later). But read them unfiltered through the eyes of others.

Here is where philosophical letters might actually give us an approachable and easy way into the minds of the past. They are shorter and less daunting than a full, fat book. Also, there is something so deeply humane and personable about the philosophical letter that you feel instantly connected to past philosophers. Yes, they were brilliant people but they also had worries, concerns, they also would fight, disagree and make up again.

I have recently read all of Baruch de Spinoza's (1632-1677) primary writings (except for his Hebrew Grammar), and this included a fair number of philosophical letters. When Spinoza died in 1677, his friends emptied his desk and quickly set to publishing all of his works, collected in the Opera Posthuma (published in 1678 but with a publication date of 1677). These collected works include his famous Ethics, a book that was so combustive and radical Spinoza didn't risk publishing it in his lifetime. It was placed on the index and it was even banned in the free-thinking Dutch Republic. But the Opera Posthuma also contains most of Spinoza's philosophical letters. So, this already signals to us that letters were deemed of great importance.

When we now think of letters we tend to conceive of them as purely private, but past philosophers in the early modern period wrote letters with the expectation that they might be circulated: copied by hand, printed, or read aloud. Thus, the letter was in the 17th century an important tool for spreading philosophical ideas.

For example, we have some letters between Spinoza and Henry Oldenburg (1619-1677). Oldenburg was a theologian who lived in England in a politically tumultuous period (which he frequently mentions in his letters), the Restoration that followed civil war and protectorate by Oliver Cromwell.

Oldenburg was a member of the Royal Society and was part of a very elaborate network of scientists and philosophers—friends and acquaintances with whom he conversed. He was a good friend of Robert Boyle, one of the founders of modern chemistry, and wrote to Spinoza to report Boyle's insights on chemical reactions. Spinoza replied with reports of his attempted replications of the experiments, with various degrees of success. Here we need to keep in mind that Spinoza, while not a scientist, did have significant practical knowledge that was science-adjacent. After he was expelled from his Jewish community for “abominable heresies and [apparently] monstrous deeds” he could no longer be a merchant in that community. So he ground lenses for telescopes, which at the time was a highly specialized craft, making him well embedded in early modern science. People such as the astronomer Christian Huygens thought very highly of his work)

Here's an excerpt of one of the printed letters of Spinoza to Oldenburg. As you can see, it is very nuts and boltsy, all about making chemical reactions that at the time were very poorly understood (no periodic table for another two centuries!). It was clear Spinoza intended Oldenburg to forward this letter to Boyle, and it may also have been read by other chemists.

Oldenburg, though no great scientist himself and with no discoveries to his name, thus played a crucial role in the development of science through his extensive correspondence (you can read about his letters here). Also, there is such warmth in Oldenburg's letters. His equanimous, sweet disposition, even in disagreement, might have helped him to forge and keep connections.

To just give you a flavor of this, here's a very brief letter by Oldenburg where he expresses worries about Spinoza's Ethics. At first, Oldenburg encouraged his friend to publish this work, which he foresaw would make an important contribution and which was circulating in manuscript form.

But by 1675, Oldenburg had heard of the radical nature of the work, and he worried that such a radical work might incite people to… taboo word… atheism. Atheism was commonly seen in the 17th century as a very corrosive ideology that would lead people to lose morality and to pursue sex, money, etc without restraint. Since Spinoza has so many radical ideas in the Ethics, for instance, he equates God with nature, denies we have free will, denies God can love us, there was probably something to Oldenberg's worry (Oldenberg was a devout Christian).

LETTER 62 : TO THE MOST DISTINGUISHED MR. B. D. S. [Benedict de Spinoza] FROM HENRY OLDENBURG

Now that Our Correspondence has been so happily resumed, Most Distinguished Sir, I don’t want to fail in the duty of a friend by neglecting it.

From the reply you gave me on 5 July, I understand that you intend to publish that Five-part Treatise of yours [the Ethics]. Let me urge you, I beg you, from the sincerity of your affection toward me, not to mix into it anything which might seem to any extent to weaken the practice of Religious virtue, especially since this degenerate and dissolute age chases after nothing more avidly than doctrines whose consequences seem to support the vices running riot among us.

As for other matters, I won’t decline to receive copies of the Treatise you mention. I should only like to ask this: that they be addressed, when the time comes, to a certain Dutch merchant living in London, who will make sure that they are passed on to me afterward. There’ll be no need to mention that you have sent me books of this kind. Provided they come safely into my possession, I have no doubt that it will be convenient for me to distribute them from here to my friends, and to get a just price for them.

Farewell, and when you have time, reply to

Your Most Devoted, Henry Oldenburg London, 22 July 1675

Note how worried this tone is, something we continue to see in later letters where Spinoza and Oldenburg further exchange ideas. Spinoza concedes he does not believe in the literal resurrection of Christ (he thinks it's a metaphor). Oldenburg is clearly disquieted and upset about this. At the same time, he tries to stay friends. Their earlier correspondence, about 10 years before, had not ended on good terms and he's trying to keep their connection alive, in spite of the geographic distance, in spite of their huge philosophical differences, and we see this up until the end (Spinoza died suddenly at the age of 44 from an illness he had been suffering from in 1677, probably brought about by the dust inhaled from grinding lenses).

When we see how we currently converse with people we disagree with, maybe we can learn something from these past exchanges?

Note, it wasn't always friendly. There is a very funny and amusing exchange between Spinoza and Albert Burgh, a former friend. Burgh became a Catholic and is now telling Spinoza to repent. Would you repent reading a letter like this? It's a nice reminder that trads need to chill (Spinoza's reply is brilliant but posting it would lead us too far and make an already too long letter even longer).

Excerpt from letter of Albert Burgh to Spinoza (excerpt)

If you don’t believe in Christ, you’re more wretched than I can say. But the remedy is easy. Repent your sins, realize the fatal arrogance of your wretched and insane reasoning. You do not believe in Christ. Why? You will say: “because the Teaching and life of Christ do not agree at all with my principles, any more than the Teaching of Christians about Christ himself agrees with my Teaching.” But I say again: are you then so bold that you think you are greater than all those who have ever risen up in the State or in God’s Church—than the Patriarchs, the Prophets, the Apostles, the Martyrs, the Doctors, the Confessors, and the Virgins, than innumerable Saints, indeed, blasphemously, than the Lord Jesus Christ himself. Do you alone surpass them in teaching, in your way of living, and in everything? Will you, wretched little man, base little earthworm, indeed, ashes, food for worms, exult that you are better than the Incarnate, Infinite Wisdom of the Eternal Father? Do you alone reckon yourself wiser and greater than all those who have ever been in God’s Church since the beginning of the world, and 15 who have believed, or even now believe, that Christ will come or has already come? On what foundation does this rash, insane, deplorable, and accursed arrogance of yours rest?

Imagine writing this, knowing it would be printed, circulated, etc.

It's worth to take a step back here and think about how the philosophical letter could become so prominent. One reason was that postal services had become more regular and reliable. In Spinoza's letters you frequently see how efficient it was, for instance, he mentions in a 1665 letter:

I shall be at this address three or four weeks longer, and then I intend to return to Voorburg. I believe that I shall receive an answer from you before then, but if your occupations do not permit it, please write to Voorburg at the following address: To be delivered in the church lane, at the house of Mr. Daniel Tydeman, the painter.

Now we tend to think of academic exchange in two modes primarily: publications in journals and books, which are relatively impersonal, and conferences. These are more personal (and fun!) and allow for interpersonal exchange, but alas, also very CO2 heavy and inequitable due to passport inequality, barriers for paying conference fees and traveling. But we can see that a wider range of options are possible. They were possible in the past, and can be today.

This brings me to a second great feature of the philosophical letter and why I am so excited at the prospect of reviving it. Because letters take place in the domestic sphere and it was socially accepted for women to write letters, a lot of women who had been formally barred from academic life in the medieval period suddenly could participate in scholarly exchange in the early modern period.

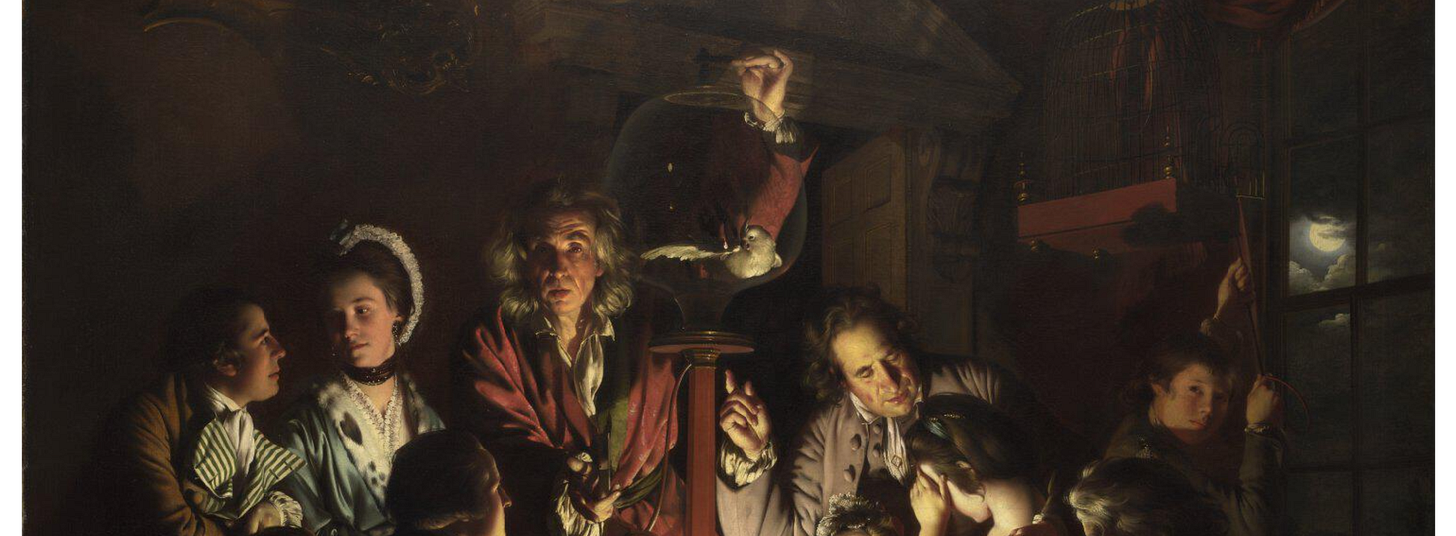

From the 17th to the 18th century, which is roughly the period that science was at its most “domestic”, with experiments done in the home (as this beautiful painting by Wright reminds us). Women were barred from the medieval university (mostly) but nothing prevented them from doing experiments in their homes, and writing philosophy to their interlocutors.

For example, among the most difficult criticisms René Descartes had to reckon with was by Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia. For Descartes, you have the mind (one substance), bodies/physical things (another substance) and then God. But if our minds/souls are a separate substance, how does the soul move the body? How does the body impact the soul? Descartes had difficulties answering her letters adequately and would end up dedicating his final book before his death Passions of the Soul (1649) to her, as the book is really an answer to her question.

So, philosophical letters really opened up a world to a broader group of (literate, of course there is that limitation) people and they allowed for exchange in a world where travel was dangerous. It was in fact so dangerous that some of the Spinoza correspondence, you see people express worries about whether someone who simply crossed from England to the Dutch Republic is OK or perhaps if the ship sank, if they had too long radio silence.

I think, given the CO2-emissions and inequitable nature of conference travel, we might consider philosophical letters, semi-public in this manner, as a way to facilitate scholarly conversation. It has never been easier, because our means of communication are even more reliable than the 17th-century postal service was.

This was a lot of info dumping, and I'm afraid that I'm mildly obsessed with Spinoza lately (this happens to many people who read him for the first time, so if you have not, you are hereby forewarned), and I am curious what you think.

Warm wishes

Helen De Cruz

Saint Louis, Missouri, June 10, 2023.

reading these type of article is blessing to be a human.