How I almost became an evolutionary psychology proponent

Reflecting on my intellectual journey with Darwin, Cosmides and Tooby

I sometimes criticize evolutionary psychology on a public forum, or even poke gentle fun of it. Whenever I do this, the evolutionary psychology (henceforth, EP) brigade swoops in and tells me that I should not criticize what I do not know. They tell me I have not read EP. They tell me I do not accept EP because I cannot handle “the truth.” The bleak, brutal truth; about sex and gender, about social relationships, about race,… my delicate woke little mind would not be able to accept it.

But in fact, in my late twenties I was steeped deeply into EP. I have read many of its founding works. My first forays into it were EO Wilson's Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (2000 anniversary edition), Jared Diamond's Third Chimpanzee (1991, I believe this was the first EP work I read, when I was nineteen or so), and Daly and Wilson's Homicide (1988).

I have published papers in two leading evolutionary psychology journals: Evolution and Human Behavior and Evolutionary Psychology, and wrote several EP-flavored papers for volumes. Even as recently as 2020, I co-authored a piece in the Sage Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, though that work is only EP in a very broad sense (see more on this below). But eventually, I lost my taste for EP, at least in its narrow, canonical construction as expounded in these books.

Here's a brief account on how I got into EP, why I got disaffected with it, and what I learned from the experience. I decided to write this because I think it is important to show how we can change our minds on scholarly matters, and why it is important always to be intellectually honest with ourselves.

Naturalism and Darwin

To explain why I was initially attracted to EP, I have to start out saying always been a thorough-going naturalist. Even in my most theistic, mystical moments I think that human minds are subject to the same forces and the same processes that are at work in the rest of nature. We're not special. I've always loved Darwin's insistence in his Descent of Man (1871) and his Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) that our minds are all of one cloth with the rest of nature. The same processes that shape animal emotions and reason shape ours, or, as he put it in Descent of Man, “the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, is certainly one of degree and not of kind.” The mind can be explained by evolutionary processes, just like the body.

The idea that human minds are a product of evolution is one I am still very strongly in favor of. Still, I am open to the empirical possibility that our minds really are subject to so many other forces that the biological, evolutionary forces that act upon them are entirely swamped. This is an open question, as Lumsden and Wilson pointed out with their metaphor of genes holding behavior on a long or short leash. But for now, I remain committed to this basic Darwinian principle, maybe precisely because I have a better grasp now on how culture fits in the total picture of how our minds work (for how I now think of culture, my forthcoming book Wonderstruck gives a sense, including in the first chapter which is freely available here).

I was about twenty when a professor teaching us about African fine art first introduced me to EP. I was an art major at the time, specializing in the study of non-western art, and I found his lectures riveting. I read the primer on EP by Cosmides and Tooby they self-published in 1997, and steeped as I was in the time in what they deprecatingly call “the standard social science model,” I found it such a revelation. I devoured the Adapted Mind Cosmides and Tooby co-edited with Barkow in 1992, and much else. I went to conferences where I met Tooby and Cosmides in person, and they were very supportive, friendly people who had read, and were enthusiastic, about my very first publication that had just come out (in Evolution and Human Behavior, 2006). I owe them a debt of gratitude for taking me serious at the time when I was a grad student and very beset by imposter syndrome, and they definitely treated me a lot better than many senior philosophers would, even much later in my career.

I went on to read Steven Pinker's How the Mind Works (1997) and The Blank Slate (2000). I won't bore you with my long EP reading list which also includes many papers, it's just to give a flavor of what I was reading. Here follow of the early seeds of doubt I had, which ultimately led me to abandon EP around 2010 or so.

Note that the following is not meant as an in-depth scholarly criticism of EP, but my best reconstruction of my thinking at the time.

The Swiss army knife

I was not sure whether we can assume from evolutionary principle that the mind is like a Swiss army knife equipped with many mental modules. Many EP proponents seem to think we can just assume, even a priori, that the brain comes equipped with different mental tools for different tasks. I wasn't sure, though I was sympathetic to the idea. I thought this is a matter for us to discover empirically.

The proposed examples such as cheater detection were underwhelming and the empirical works that were supposed to support these had plausible alternative explanations. I remained unsure that humans have so many mental modules and especially that we would have a cheater detection module. It's possible, of course. Yet, I found the ideas of Spelke, Carey and other developmental psychologists, who outline much broader domains of core knowledge (social cognition vs EP's cheater detection) much more appealing. And I ended up finding core knowledge more fruitful for my own research.

The Pleistocene

In addition to mass modularity, I had doubts about the focus of EP on the Pleistocene in their concept of the EEA (the Environment of evolutionary adaptedness, at the expense of other periods. This concept is, by the way, adapted from John Bowlby (1969) in the context of attachment theory. At the time, I had just majored in anthropology of art and archaeology and increasingly began to see how anomalous the Pleistocene is in our total evolutionary history. Yes, it's the large period when humans split from chimpanzee/hominin common ancestor, the largest span of time in our evolutionary history when we diverged. But the Pleistocene was colder than today and quite variable, much more so than the stable and warm Holocene (something Richard Potts has noted). Pleistocene humans were egalitarian, a situation that only shifted in the later Pleistocene with rising inequality. Pleistocene hominins such as Neanderthals and Homo ergaster took care of each other, including disabled individuals, in ways that we often don't see in earlier or later periods.

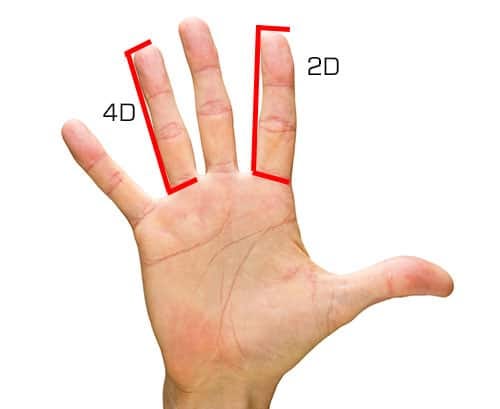

Finger ratios

A lot of EP papers in the first decade of the 2000s were about fingers. This was a period when I read a lot of EP and I didn't know what to make of these papers. More specifically, they focused on the ratio of the second to the fourth digit as a proxy of prenatal exposure to testosterone, and thus as a proxy to more masculine-coded behaviors. I could not get into this work. I felt it was silly, and bordering on palmistry. Again, I'm not writing a detailed critique of EP but an explanation of why the fields spoke less and less to me. It is possible that a certain 2D-4D ratio can explain which financial traders are successful, but I'm skeptical.

EP, gender and sex

I enjoyed The Blank Slate, one of the four books by Pinker I read in depth and detail. I enjoyed his Language Instinct, as well as his paper with Paul Bloom in BBS on the topic. But as I went on to read more and more Pinker books, I found them less and less compelling. Blank Slate was not as good as How the Mind Works (in my view, I liked HMW and the discussion with Fodor it generated in The Mind Doesn't Work That Way (2001). Then I unfortunately still read The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), and I ought to have stopped but I read Enlightenment Now (2018), already firmly in my post-EP period.

I did not think Pinker's takes on gender were good. He promoted a kind of sex-based essentialism in The Blank Slate that did not seem backed up by careful reading of the evidence or anthropology, but by cherry-picked examples. One of his central case studies was a boy in the 1970s who lost his penis following a botched circumcision. The parents decided to raise him as a girl and in addition agreed to have him castrated and undergo surgery. In spite of this, the boy strongly felt a male gender identity. I do not think this case demonstrates that sex equates to gender. Indeed, it shows a specific gender dysphoria that seems to resonate with the experiences of many transgender individuals I talked to, even in gender-affirming surgery, as this passage makes clear:

She [sic] ripped off frilly dresses, rejected dolls in favor of guns, preferred to play with boys, and even insisted on urinating standing up. At fourteen she was so miserable that she decided to either live her life as a male or end it, and her father finally told her the truth. She underwent a new set of operations, assumed a male identity, and is now happily married to a woman (Pinker, Blank Slate, 349).

The same I felt was true of such works as The Mating Mind (Miller, 2000) which try to explain complex phenomena such as art, humor and literature through the lens of sexual selection. I do think that sexual selection has helped to shape some of our cognitive architecture, but this kind of reductionist explanation does not work (maybe most keenly shown in the fact that Miller has difficulties explaining women's art and female artists, except as a kind of spandrel/byproduct of them having to be able to appreciate art made by men).

Overall

Overall, my main reason for not liking a lot of what I was reading was at the time not political. My political orientation then was much different from now, and I think you might describe it as closer to IDW (pro free speech, against “cancel culture” which I think was not called that at the time, against identity politics).

My main reasons for becoming disaffected with EP was that they were not sufficiently led by evidence, not sufficiently cognizant of changes happening in evolutionary biology, behavior biology, cognitive ecology etc., such as evo-devo and niche construction. The modules they landed on such as cheater detection seemed to me less interesting and fruitful compared to, for instance, evolutionary game theory which models how we deal socially with others (e.g., Meeting at Grand Central by Cronk and Leech, 2013).

My initial reservations with EP led me to read a lot more paleoanthropology, archaeology, and the work by people who study culture in a broader evolutionary framework such as Joseph Henrich, Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson, particularly the book Not by Genes Alone (2005). And so, by about 2010-2013 or so, I had moved away entirely from EP, at least in its narrow conception.

Reflecting on our intellectual journeys

I think it's sometimes worthwhile to reflect on our intellectual journeys. We do not come with our current views in their fully-fledged forms. We change our minds. We should not be beholden to our earlier views due to sunk cost thinking. However, I think it's perfectly fine to maintain some ideas as central/bedrock that we only shift if we find very strong reasons to do so. For example, I take both naturalism and Darwinian continuity (of humans with other animals, the rest of nature) as given.

I still think something broadly speaking like EP must be true. But the specifics of what it is, or how we should best approach it, are up to our best scientific practices.

We discount how much of our current views are due to luck, circumstance, indeed, even sunk costs. An inspiring professor, a book we read at the right time can make a big impact on our thinking, can make a big change down the line. How many women have not fallen into gender critical discourse because some of it seemed to them continuous with the second-wave feminism they knew? Had I stuck it out with EP and the people whom I knew and conversed with, and admired at the time, what would my views look like now?

We cannot entirely insulate ourselves from the specific circumstances in which we find ourselves of luck of what we end up reading or even the crowd we fall in with. But we can continue to critically appraise our views, be open to new ideas, and to follow our thinking where it may lead.

re your point about our ideas being formed by chance...I think there's a good bit of evidence that one major predictor of one's political opinions are your parents' political opinions.

the only Pinker book I read was Better Angels...which I thought was really sloppy and also just intellectually uncurious in disturbing ways.

Your tweet about philosophers and evolutionary psychology and this post encouraged me write a blog post about my understanding of evolution and philosophy which I have been thinking about sometime. Thank you.