Her lively and sweet countenance

Did European people in the early 1800s perceive the human face differently from us?

In Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) polar explorer Robert Walton tells his sister in a letter how he rescues a stranger from the ice. He describes the stranger, who turns out to be Victor Frankenstein, as follows:

I removed him to my own cabin, and attended on him as much as my duty would permit. I never saw a more interesting creature: his eyes have generally an expression of wildness, and even madness; but there are moments when, if any one performs an act of kindness towards him, or does him any the most trifling service, his whole countenance is lighted up, as it were, with a beam of benevolence and sweetness that I never saw equalled—Mary Shelley, Frankenstein (letter IV)

I used to gloss over the word “countenance,” thinking it is merely a synonym for “face". But it is not.

Countenance is much more encompassing than what we now mean by “face”. It is the way one's face and other physical features dynamically express one's inner state. Together with one's “air” the countenance was part of the way someone's body gave clues to their very private and elusive soul.

In Shelley's novel, though the rescued man seems mad, there are glimmers of a sweetness and benevolence you can read in his countenance. Together with other words, such as “air” and “presence” we can surmise that 18th century Europeans had a complex and sophisticated set of concepts to evaluate someone's physical appearance. You can see it in the guide by Charles Le Brun, in his Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions (1698), a popular and much-reprinted method for drawing “the passions” as reflected in the countenance of the sitter. Inspired by Descartes's Passions of the Soul, Le Brun believed that our emotions are closely linked to the state of our soul. Emotional expression gives us a window into someone's essence of being.

In Pride and Prejudice (watch this wonderful well-researched video by Ellie Dashwood, which inspired this post) countenance plays a crucial narrative role. Mr Darcy goes from thinking that Elizabeth Bennet is “tolerable, but not handsome enough to tempt me” to “one of the handsomest women of my acquaintance.” This is not simply a story where he appreciates her personality and because of that finds her more beautiful.

No, Mr Darcy gradually discovers her beauty by paying closer attention to her countenance: the dynamic way she expresses her personality, her wit combined with sweetness, her liveliness wins him over.

Pride and Prejudice had as original title First Impressions. As Jane Austen is aware, looks can deceive. For example, Mr Wickham is a dishonorable man who several times seduces young girls, including Mr Darcy's sister and Lydia Bennet. But he gets away with it, and manages to deceive Elizabeth Bennet because of his pleasing countenance: “The officers of the ——shire were in general a very creditable, gentlemanlike set and the best of them were of the present party; but Mr, Wickham was as far beyond them all in person, countenance, air, and walk.”

There's a second moment in the novel where countenances deceive, notably in Jane Bennet. She really does love Mr Bingley but gives little outward signs of affection. Together with the relative difference in fortune, Jane's shyness gives Mr Darcy enough reason to try to separate his friend from Jane Bennet. As he later explains to Elizabeth in a letter, “But I shall not scruple to assert, that the serenity of your sister’s countenance and air was such as might have given the most acute observer a conviction that, however amiable her temper, her heart was not likely to be easily touched.”

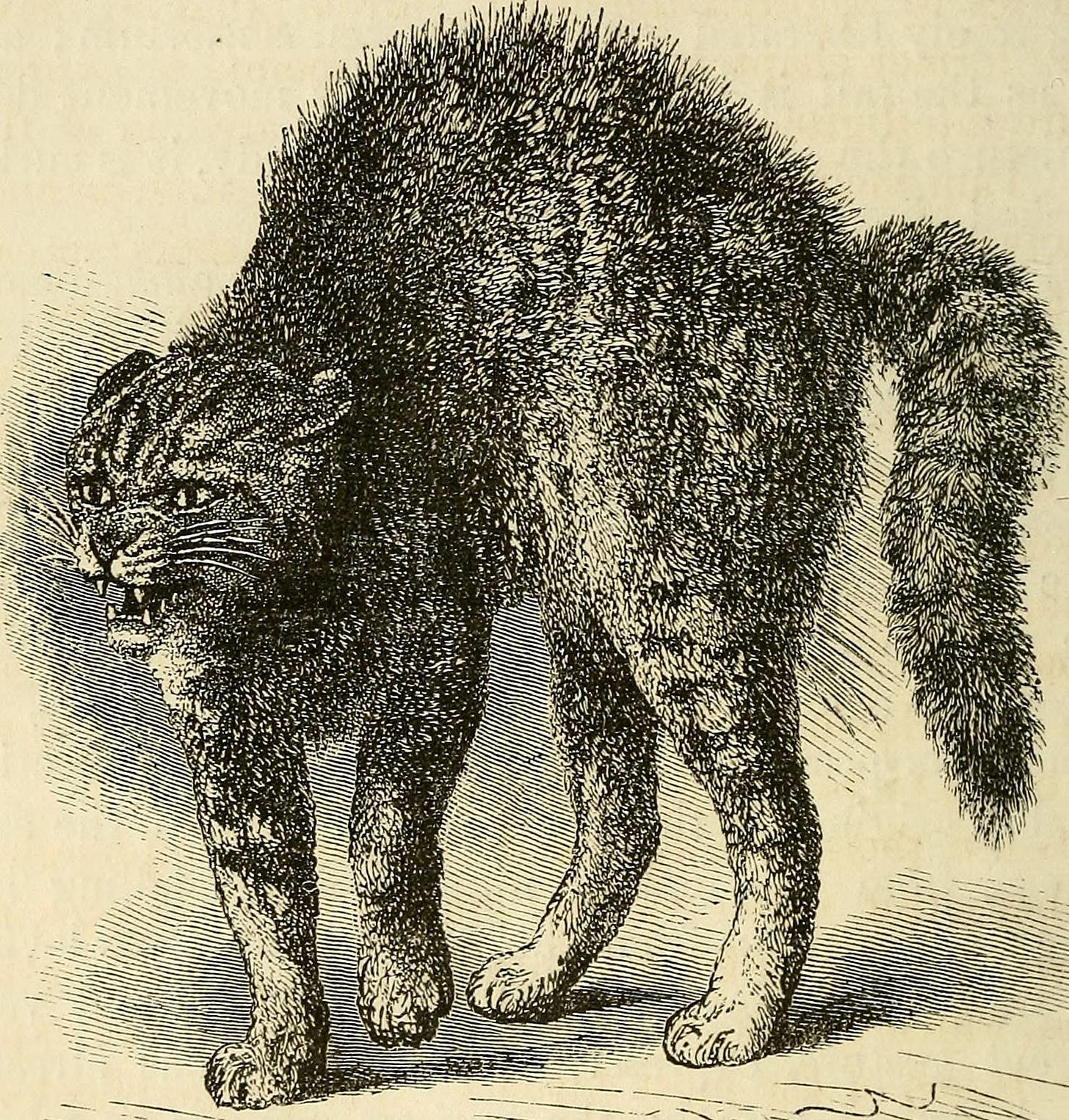

By the time Charles Darwin wrote The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), theorizing about countenance had reached its apex. If a countenance is the window of the soul, and the soul (it was believed at the time) uniquely human, then we can expect endless gradations in emotional expressions. Going against these ideas, Darwin insisted our emotions are innate and adaptive, with only modest scope for cultural variation, and that they are continuous with animals, as we can see from this image from the book.

This biologizing of emotions demystified them to some extent, and the talk about countenance went out of fashion. There were undoubtedly other reasons for this demise. As we can see in this Google ngram, “countenance” became popular in the late 18th century, and then declined from around 1840 onward. As a result, when we read books that were written in that period, our way of aesthetically and even morally evaluating people is different from them, in a way that perhaps makes it difficult to understand them. Or do we still evaluate “countenance” but without having the vocabulary?

This post made me immediately think about Charlotte Brontë's use of 'countenance' in "Jane Eyre", and the idea that the countenance is something "legible" that can be "read". Just a few of the many examples:

1. Where Rochester is interviewing Jane about her background:

"Arithmetic, you see, is useful; without its aid, I should hardly have been able to guess your age. It is a point difficult to fix where the features and countenance are so much at variance as in your case."

2. The much beloved scene in the garden, where Rochester proposes, and Jane questions his sincerity:

“Mr. Rochester, let me look at your face: turn to the moonlight.” “Why?” “Because I want to read your countenance—turn!” “There! you will find it scarcely more legible than a crumpled, scratched page. Read on: only make haste, for I suffer.”

Found this interesting analysis by an ex-Latter-Day Saint. It seems that the notion of countenance is quite prominent in the LDS theological culture. youtube.com/watch?v=awVrBi4LiAQ