American Christianity finally did it

As long as I can remember, I've been a Christian. I was baptized so it was not my decision initially, and I went to Catholic school from age six to eighteen. My mother is a Belgian Catholic. My father is a Malaysian with a Catholic Portuguese (Eurasian) background who grew up as a religious minority in Malacca. He would talk about how yes, Christians were tolerated, but no more than that. Building licenses for churches were easily revoked, and Christians weren't allowed to use the same word for God Muslims did, even though they had an ancient tradition of doing so (now it seems that the high court has ruled in favor of the Christians). When I was little, we had my father's Muslim and Hindu friends who frequented our house. So this has long instilled in me that Christianity is not a default.

For me, Christianity has been a conscious choice, a decision. I reaffirmed it during my confirmation at age twelve. I sang in a church choir (twice, in Belgium and in the UK) for several years. I was part of a youth group from age 14 to 18, and taught Sunday school as an adult. In addition, I am a long-time member for the Society for Christian Philosophers and have done various forms of service for them. I have written over 30 papers and three books (two co-authored) in Christian philosophy, on topics such as the Fall, the noetic effects of sin, aesthetic experience, and God (check here for some works).

Significantly, I had two profound, life-altering religious experiences that gave me very vivid, first-hand evidence of … something. I don't know what? Something personalistic that does not fit the bread-and-butter naturalism we are implicitly told to accept as the most reasonable position. I also have had, throughout my life, a sense of teleology or nudges about what I should do that have the forcefulness that Kant undoubtedly was referring to when he expressed awe for “the moral law within.”

I give you all this as background to say that it's significant for me, coming from all of that, that I identify less and less with Christianity. The problem is my co-religionists. American Christianity is so steeped in white supremacy, a sense of superiority, gun culture and the control of other people's bodies and healthcare decisions. There is a kind of smugness with the expectation of the rapture, or the assurance of Heaven I find particularly odious. When the Supreme Court expectedly slashed the right to abortion, I realized that the cognitive dissonance had become too great.

One fine Sunday morning as I was considering my increasing mental resistance to go to church, I realized I could not do it anymore. And so I decided to stay home.

Reading Spinoza

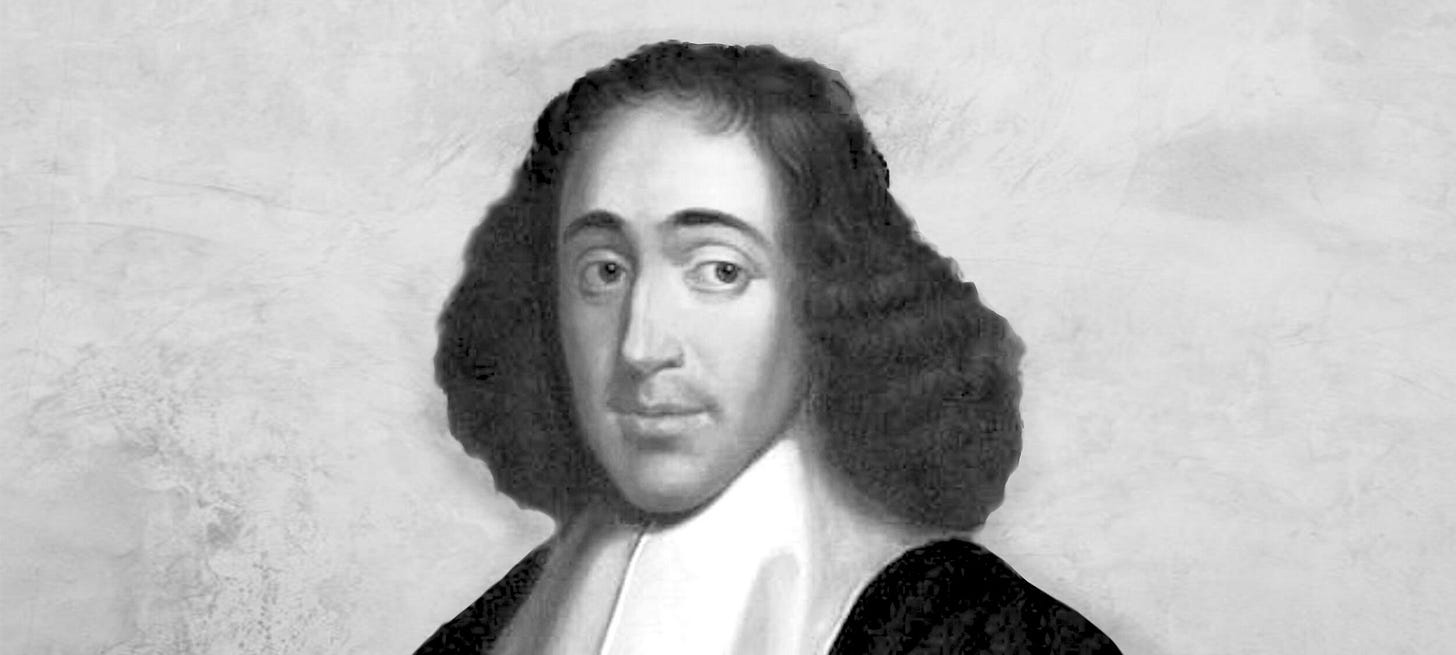

I'm on research leave for a project on oneness (investigating all sorts of monistic metaphysical ideas from different traditions) and I am finally reading Spinoza. I say “finally” because even though I've been a philosopher for a long time, I only now am reading Spinoza (at the age of 44, coincidentally, the age Spinoza died). I started out with the Ethics but I was put off by the strange format (the subtitle of the Ethics is Demonstrated in Geometrical Order). He uses definitions and axioms, and then derives propositions which he argues for.

I gave up halfway part I and then decided to read his Theological-Political Treatise first, a book that is infamous for arguing in 1670 that the Bible is the work of fallible human beings, that it is riddled with inconsistencies, that you cannot rationalize the Bible into something that makes sense (as Maimonides argues), nor can you rely on the “instigation of the Holy spirit” (as Reformed thinkers, in Spinoza's time and recently, such as Alvin Plantinga have proposed). The biblical scholarship is of course outdated but it is surprisingly good, with a deep knowledge of Hebrew and sensitivity to the historical context. The book is also a passionate defense of free speech, democracy on a broad basis rather than aristocracy or oligarchy, and much more. I instantly fell in love with the book and with Spinoza's writings, and so I decided to try the Ethics again after reading all of the early letters, the Short Treatise on God, Man and his Wellbeing and a few other things.

Now, I'm still going through the Ethics slowly but one thing I find helpful is to try to see its clunky form as integral to the work. Spinoza spent most of his active research life fine-tuning this book (it was published posthumously in 1677) and the form wasn't decided on a whim (Spinoza experimented with many different forms, even—maybe not his best writing—with philosophical dialogue).

At first, I was trying to look at these arguments for his conception of God and the relationship of God with the created order and didn't feel very impressed (like his argument that there can only be one substance seems a bit weak, or his argument that there are infinitely many modes of this substance). But now I find it more useful to see the framework as a kind of holistic edifice, a conception of God that is very different from the surrounding theistic traditions (the Jewish tradition Spinoza grew up in, and the Christian tradition of most of his friends and intellectual interlocutors). He denies that God and the natural world are two different substances, that God is like a person (or even a person) who could freely decide what kind of world to create, that God has certain aims in mind when creating, that we have free will and so on.

So, you get an alternative metaphysics and the ultimate proof of the pudding is not so much the formal proofs but whether this metaphysics can be salutary for you, help you increase your wellbeing or feeling at peace with/in the world. The key notion for Spinoza is blessedness or beatitudo here, and I look forward to reading Alex Douglas’s book on this topic.

Once you get into it, the geometric framework of the Ethics has a strange soothing effect, it helps you to calm your passions and to focus on that broader picture. QED.

Why it's OK to DIY your own spirituality

Spinoza, being expelled from his community, completely DIY-ed his own spiritual vision. Now I'm not Spinoza and very few people have the intellectual scope to do something of this calibre. But at a more modest level, I think it's fine and maybe even intellectually honest and virtuous to DIY your own spirituality. You don't need to pick from a menu. You certainly don't have to choose between theism and the kind of scientific atheistic naturalism that are often presented as binary options.

Regarding Christinaity, the alienation from Christianity I am feeling now comes from what Joshua Blanchard calls unwelcome epistemic company. If Christians are like this, do I want to be part of that group? But there are other issues. I have always had a strong anti-authoritarian sense. I do not like sole rulers, monarchies, oligarchical rule, or other people deciding what I do. This seems to run counter to the Christian ethos of God as the ruler that we owe gratitude, respect, obedience to. I have never enjoyed the idea of an afterlife. I know this is supposed to be one of the perks, but I think non-survival is preferable (though I like to think the universe, and intelligent life forms continue to exist). I am not sure where to go from here.

I have argued in my book Religious Disagreement for the view that you should conciliate in your religious views, that is, that you should take seriously into account (religious and other) beliefs of others when evaluating your own. This doesn't mean spinelessness, but you do not get a free card to simply break symmetry and believe what you grew up with. This is especially important as our religious beliefs have so many connections to our other beliefs. Hundreds of thousands of people in the US died because of their Christian beliefs from the pandemic due to vaccine denial. If your religious affiliation can get you killed, well you should examine them with care. This includes being sensitive to evidence for your beliefs (here is a nice recent paper by Katherine Dormandy defending evidentialism about religious beliefs).

Learning about the religious views of others can give you relevant evidence. Not just relevant second-order evidence about what others believe, but also crucially, how big the space of possibilities is. How we can make sense of our world, which is the center of a religious attitude. If none of the options satisfy you, then you can also create your own ideas and DIY your own religious views. You can try to find your own path, and that path is the path of least resistance. By that I do not mean laziness in your religious belief, but rather a path that leads to the least amount of doxastic conflict.

So, rather than spinelessness, being open-minded about religious views (including unorthodox ones like Spinoza's) gives you more original ideas, helps you to recognize the value of different ideas, and to develop more intellectual courage. It's a big world out there.

About this newsletter: I'll be posting more musings as I go on this journey and obviously also on my long-term passions of art, philosophy, politics, and literature. You can subscribe for free to get more! I am a Philosophy Professor, I hold the Danforth Chair in the Humanities at Saint Louis University, and you can find more about me here.

American Evangelicalism seems to have become toxic in a very literal way, eating away at people's Christian faith. Americans make Christianity seem unbelievable. Faith seems to consist almost entirely of social evidence, which is sometimes overwhelming and sometimes absent.

Speaking of evidence, the link to Katherine Dormandy's defense of religious evidentialism is broken. Would you mind sharing that again? Thank you for helping ordinary people think intelligently about belief.

"I'm on research leave for a project on oneness (investigating all sorts of monistic metaphysical ideas from different traditions)....." Hi, I'm curious if in your research project, you've looked into Schopenhauer's notion of will as the fundamental essence of everything that exists, and if so, what do you think of that notion of the "world as will"