Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds - fifth evening

Translated from Entretiens sur la pluralité des Mondes by Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle (1686, first edition)

A translation by Helen De Cruz

(Draft of 02/19/2024. This is a translation for an anthology I am co-editing with Rich Horton and Eric Schwitzgebel of classic and more recent philosophical science fiction. Please refer to the final published edition, as this still needs to undergo some editing)

Translator's introduction

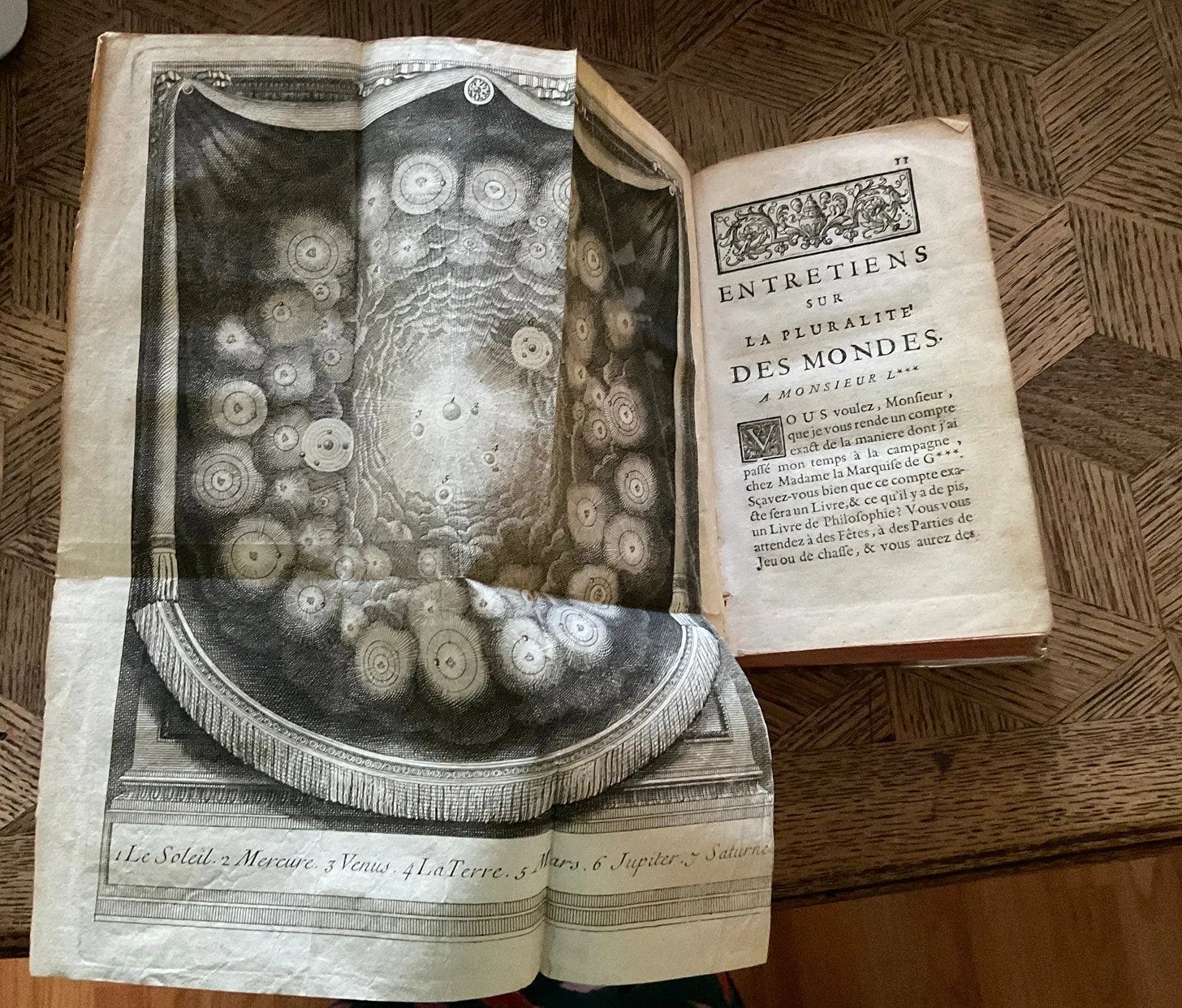

This excerpt is translated from the first edition (1686) of Entretiens sur la pluralité des Mondes, a novel by the French philosopher and Enlightenment scholar Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle (1657-1757). I made this translation from a facsimile online copy stored at BnF Gallica.

In this book, which is styled like a novel, Fontenelle aimed to acquaint the lay reader with the latest findings and theories in astronomy. Fontenelle lays out these astronomical theories in a series of philosophical conversations over five successive evenings between a philosopher and a marquise as they stroll in her gardens under a starry sky. Though the marquise is not educated, she is very quick-witted and immediately grasps the implications of the dizzying picture that the philosopher explains in a poetic, yet (for the time) scientifically precise fashion.

Fontenelle aimed this book at a female audience. Women were at that time barred from many formal means of learning such as universities and some of the new learned societies. It's no exaggeration to say that Fontenelle, who was a feminist, was able to achieve more for women's education through this book than many other people at the time who wrote explicit treatises in favor of women's education. The book was an enormous success with many translations, reprints, and new editions. It started a movement of science fiction for women, such as Francesco Algarotti’s Il Newtonianismo per le dame (1737). Immanuel Kant mentions Fontenelle in a deprecating manner when he rails against educating women in his essay The beautiful and the sublime (1757), disparaging women who took education from astronomy from Fontenelle, "The beauties can leave Descartes’s vortices rotating forever without worrying about them, even if the suave Fontenelle wanted to join them under the planets.”

Fontenelle begins by presenting the Copernican system in the first evening. This is not surprising given the 1686 publication date, but there was still a lot of resistance to this system from religious and political powers, such as the Catholic Church. By the fifth evening, Fontenelle draws out the full implications of this system, which goes significantly beyond Copernicus. As the Marquise exclaims, "Are you telling me next that The Fixed Stars are as many suns?" Fontenelle’s explanation of astronomy draws on Descartes’s notion of vortices, of which Fontenelle was a huge fan, and which you will see explained throughout Fontenelle's fifth evening. Belief in extraterrestrial life in this period is very common, with authors such as Kant and Kepler expressing confident belief in their existence, which explains why Fontenelle’s philosopher is so confident in his belief in alien life.

Throughout this excerpt, Fontenelle, through the gallant and charming character of the philosopher, ponders weighty questions: What does it mean that we are like little flickers in the scale and time of the universe, or in Fontenelle’s beautiful metaphor, roses who look upon a gardener, never see him change, and thus decide that the gardener is unchanging? What does it mean that our sun just appears as a star when seen from an exoplanet? Will all star eventually go out, and does this include our Sun too? He examines the limits of philosophy and its relationship to our thirst for knowledge and our sense of wonder. Or, as the philosopher puts it, "All philosophy is based on only two things: a curious mind and bad eyesight. Because, if you had better eyesight you’d be able to see if these stars are Worlds or not. If, on the other hand, you were less curious, you wouldn’t be anxious to know about it, which amounts to the same thing."

Letter To Mr. of L***

You'd like, sir, that I give you an account of how I spent my time in the countryside with Madame the Marquise of G***. Do you realize that this will take a book, and, which is worse, a book of Philosophy? You’re expecting festivities, games, or hunting parties, but instead you will have planets, Worlds, and vortices; and I will hardly speak of the other things. Fortunately, you're a philosopher; you won’t make fun of another one. Maybe you’ll find comfort in the fact that I have recruited Madame the Marquise to be part of philosophy. We could not have made a more impressive acquisition, for I count beauty and youth among things of great price. Don’t you believe that Wisdom would be able to present herself successfully to human beings without looking a bit like the Marquise? Especially if she could make her conservation just as agreeable, I assure you that everyone would run after her.

However, don’t expect to hear marvels. When I will tell you the story of the conversations I had with the Lady, you must have as much spirit as she has, to repeat what she has said, in the same way as she has said it. You will see her simply have the same disposition to understand everything, which she in fact has. I take her to be a Scholar, because of the extreme ease she has to become one. What does she lack? Opening her eyes to books is nothing—many people who have done this their whole lives I would refuse, if I dared, to give the name of “Scholar.”

For the rest, Sir, you will owe me a favor. I know that before we enter the details of the Conversations I had with the Marquise, I'm supposed to describe the castle where she went to spend the fall. We have often described castles with the smallest of pretexts, but this time, I will let it slide. It suffices to know that when I arrived at her place, I didn’t find any company, and I felt quickly at ease. The first two days had nothing remarkable in them, and were spent exhausting all the news from Paris, where I had just come from. But after that came the Conversations that I want to talk to you about. I will divide them up into evenings, because in fact we only had these Conversations at night.

Excerpt of the First Evening

One evening after dinner we went for a walk in the park. A refreshing breeze rewarded us after a hot day that wiped us out. I feel, Sir, that will make a description, but there’s no way to spare you of it, because the topic brings me there necessarily. The Moon had only been up for about an hour, and its rays only reached us from between the branches of the trees, making a pleasant mix of a vivid and strong white against the greenery that appeared black. Not a single cloud robbed us of the least star. They were all of a pure and sparkling gold, further heightened by their blue background. This spectacle made me dream. Perhaps without the Marquise I would’ve dreamed for a long time. But how could I abandon such an amiable lady to the Moon and stars?

"Don’t you find," I asked her, "That the daytime isn't as lovely as a lovely night?"

"Yes," she replied, "the beauty of daytime is like a blonde, who is more brilliant. But the beauty of nighttime is like a brunette, who is more touching."

"You are quite generous," I replied, "To grant brunettes this advantage since you are not one. It’s true though that the day is the most beautiful in Nature, and that the heroines of novels--because there is nothing more beautiful in the imagination--are almost always blonde."

"It must be beautiful if it moves you," she replied. "Admit that the daytime has never thrown you in as sweet a reverie as the one I saw you were about to fall into just now, on the eve of this beautiful night."

"I agree," I answered, "but in return a blonde such as you will make me dream even more than the most beautiful night in the world with its brunette beauty."

***

Finally, to give her a general idea of philosophy, here’s the line of thought in which I threw myself. "All philosophy," I told her, "Is based on only two things: a curious mind and bad eyesight. Because, if you had better eyesight you’d be able to see if these stars are Worlds [solar systems][1] or not. If, on the other hand, you were less curious, you wouldn’t be anxious to know about it, which amounts to the same thing. But we want to know more than we can see, therein lies the difficulty … In this way, true philosophers spend their lives not quite believing what they see, and trying to find out what they cannot see."

The Fifth Evening

The Marquise became very impatient to know what would become of the Fixed Stars.

"Are they inhabited, like the planets," she asked me, "Or aren't they? What will we do about it?"

"Make a guess if you feel like it," I replied. "The Fixed Stars are at least fifty million leagues removed from the Earth. If you ask an astronomer, he'd put them even further away. The distance from the Sun to its furthest planet is nothing compared to the distance between the Sun or the Earth and the Fixed Stars, and we’re barely able to measure it. Their light, as you can see, is bright and dazzling enough. If they received it from the Sun, it should be the case that they receive it faintly after a trajectory of fifty million leagues. It should be the case that by a reflection which still weakens much, they send it back at the same difference. It seems impossible that one light had erased a reflection and that traveled two times fifty thousand leagues would have this force and this vivacity as those of the Fixed Stars. Therefore, they are luminous in themselves, and all are—in one word—so many stars."

"Am I mistaken," the Marquise exclaimed, "In where I think you want to lead me? Are you telling me next that The Fixed Stars are as many suns, our Sun is the center of a vortex that turns around it, so why could not each Fixed Star be the center of a vortex that has a movement around it? Our Sun has planets that it lights up, why could not each Fixed Star also have planets that it illuminates?"

"I can only reply to you," I said, "what Phaedra said to Oenone, You've called it."[2]

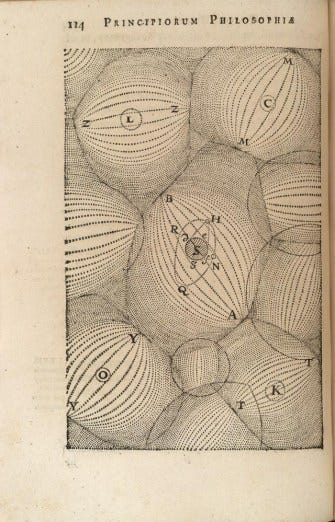

"But," she continued, "See here a universe so large that I am lost. I don't know where I am anymore, I am nothing. What! Everything would be divided in vortices jumbled together confusedly one among the others? Every Star the center of a vortex perhaps as large as the one where we are? All this enormous space that contains our sun and our planets, is it really just a tiny plot of the universe? As many similar spaces as there are Fixed Stars? This confuses me; troubles me; disgusts me."

"As for me," I replied, "This makes me feel at ease. When the sky was this blue vault, where the Stars were nailed to, the universe seemed small and narrow to me. I felt oppressed in it. Presently, now they have given much more scope and depth to this vault, and divided it up into thousands and thousands of vortices, it seems that I breathe more freely, and that I'm in a larger air, and assuredly the universe has a completely different magnificence. Nature has spared nothing in producing it. She has made a profusion of richness that is exactly worthy of her. Nothing is as beautiful to present itself as this prodigious number of vortices, where each center is occupied by a sun that makes the planets turn around itself. The inhabitants of a planet of one of these infinitely many vortices see the luminous centers of the vortices in their neighborhood, but they have to be careful to be able to see the planets, which only have a faint light, borrowed from their sun, never pushing it beyond their World."

"You offer me," she said, "A perspective that is so vast that there is no end in sight. I see clearly the inhabitants of the Earth, then you let me see those of the Moon and the other planets of our vortex with sufficient clarity, but less than those of the Earth. After them come the inhabitants of the planets of other vortices. I confess that they are absolutely in darkness. In spite of my efforts to see them, I can hardly do so. In fact, are they not nearly annihilated by the expressions you have to use to talk about them? You're obliged to call them the inhabitants of one of the planets, of one of those infinitely many vortices? We ourselves, to whom the expression is applied: Confess that you would hardly be able to disentangle us from among so many Worlds. For myself, I begin to see an Earth so scarily small that I do not feel, from now on, any enthusiasm for anything. Surely, if people have a desire to better themselves, to make plans, to spend all this effort, well, it's because they don't know about vortices. I imagine that my laziness can profit from my new insights: when people reproach my indolence, I'll answer: Ah! If only you knew what the Fixed Stars really are!"

"It was important that Alexander [the Great] did not know," I replied, "Because a certain author who holds that the Moon is inhabited says very seriously that it was impossible that Aristotle held such a reasonable opinion (how such a truth could have escaped Aristotle!). But they didn't want to say anything about it, for fear of displeasing Alexander, who would've fallen in despair to see a World that he could never have conquered. All the more reason did they have to make the vortices and the Fixed Stars into a mystery, if they had known about them at the time. It would give him too much heartache to talk about them. As for me, who knows them, I'm quite angry to get no use out of my knowledge of them. They don't help me to get rid, according to your reasoning, of my ambition and my worries, and I don't at all have those particular ailments. A bit of a soft spot for what is beautiful, that's my chief weakness, and I don't believe that the vortices can do anything about that. The other Worlds make our own so tiny, but they do not in the least spoil your beautiful eyes, or your pretty mouth--these will always retain their price in spite of all possible Worlds."

"It's strange that love," she answered, laughing, "Can save itself from anything and that there is not a single system that can harm it. But tell me frankly, is your system really true? Don't hide anything from me, I'll keep your secrets. It seems to me that your system rests on a tiny, all too light basis. A fixed star that is luminous by itself like the sun, consequently should be like the sun, the center and the soul of a World, and should have planets that turn around it. But is this an absolute necessity?"

"Listen, Madame," I replied, "Since we are always happy to mix follies and gallantry in our most serious discourses, let's say mathematical reasoning is like love. You would never grant so little to a lover, who soon after would be granted more, and even more, and eventually you go very far with him. In a similar way, grant a mathematician the smallest principle, he will draw a result for you, then you will have to grant him that also, and from this result another follows, and in spite of yourself he will take you so far that you would scarcely have believed it. These two kinds of people always take more than they're offered. You agree when two things are similar in all that appears to me, I can believe them also similar where they don't appear to me, if there is nothing else that prevents me. In this way, I've concluded that the Moon is inhabited, because she resembles the Earth, the other planets, because they resemble the Moon. I find that the Fixed Stars resemble our Sun, and so I attribute to them everything it has. You're too much involved to pull back, I'm afraid you have to cross the bridge with good grace."

"But," said she, "Based on this resemblance that you make between the Fixed Stars and our Sun, it should be the case that the people from another vortex see our sun as a tiny Fixed Star, which only shows itself to them during their nights."

"Without a doubt," I replied. "Our Sun is so close to us in comparison to the suns of the other vortices, that its light has infinitely more force on our eyes than theirs. We can therefore only see the sun when we see it, as it erases every other star. But in another large vortex, another sun will dominate, and it will erase in its turn ours, which will only appear at night with the other foreign suns, that is to say, the Fixed Stars. We stick them to this great vault of the sky, and it becomes part of some Bear or some Bull. For the planets that turn around it, our earth, for example (because you cannot see it from that far), they won't spare a thought for. So all the suns are suns of the day for the vortex where they're placed ,and suns of the night for all the other vortices. In their world, they are the only ones of their kind, elsewhere, they only add to a number."

"Isn't it the case," continued she, "That the Worlds in spite of this equality would be different in a thousand respects, because a baseline of resemblance still allows for infinite differences."

"Assuredly," I said, "but the difficulty lies in guessing where those differences lie. What do I know? One vortex has more planets that circle around its sun, another has fewer. One has subsidiary planets, which turn around the largest planets, the other has none. Here all planets are gathered around their sun and make a little pack beyond which extends a huge empty space, which reaches until the neighboring vortices. Elsewhere the planets take their orbit near the edge of the vortex and leave the center empty. I don't even doubt that there might be some vortices that are deserted, without any planets, and others where the sun is not exactly at the center, and takes the planets with it, others where the planets rise or lower themselves with respect to their sun depending on the equilibrium that keeps them suspended. Well, what do you want? This is quite enough for a man who has never left his own vortex."

"This is hardly enough," she replied, "Given the number of Worlds. What you say doesn't suffice for five or six, and I can see thousands of them from here."

"What will it be then," I answered, "If I told you that there are many other Fixed Stars besides the ones you can see; that with telescopes we are discovering an infinite number of them that never show themselves to our eyes, and that in a single constellation where you can count perhaps twelve or fifteen, there are so many stars as you can observe in the whole of the sky?"

"I ask for mercy," she cried, "I surrender! You overwhelm me with Worlds and vortices!"

"I know well," I added, "What I am still keeping from you. Do you see that whiteness that we call the Milky Way? Do you realize what it is? An infinity of tiny stars, invisible to the eyes because of their smallness, and strewn so close together that they appear to form a continuous whiteness. I wish you could see with a telescope this anthill of orbs, and these seeds of Worlds (if such expressions are permitted). They look a bit like the Maldives Islands, these dozens of thousands little islands, or sandbanks, separated only by sea channels that you can almost jump over like a ditch. Similarly, the small vortices of the Milky Way are so tight together, that it seems to me that someone from one World could talk to another, even shake their hand. At least I believe that the birds of one World can easily go to another, and that one could train pigeons to bring letters like they do here in the Levant. These tiny Worlds are apparently a departure from the general rule that the sun of one vortex erases whatever appears from all the foreign suns. If you are in one of the small vortices of the Milky Way, your sun is almost not closer to you, and as a result, has not visibly more force on your eyes than five thousand other suns of the neighboring vortices. You will therefore see your sky sparkle with an infinite number of fires, which are very close together and not far removed from you. When you lose sight of your particular sun, there will be enough others, and your night will not be less bright than the daytime, at least, the difference will not be perceptible. To say it more precisely, you'll never have nighttime. They would be quite surprised, the people from these Worlds, accustomed as they are to a perpetual clarity, if anyone told them there are unfortunate beings who have true nights, who are steeped into profound darkness, and when they rejoice in the light, only see a single sun. They will regard us as beings disgraced by nature, and they will tremble in horror at our condition."

"I won't ask you," said the Marquise, "If there are moons in the Worlds of the Milky Way. I realize that they won't have any purpose for the principal planets that have no night, and that elsewhere the spaces are too narrow to embarrass themselves with these paraphernalia of subordinate planets. But do you realize that by multiplying these Worlds so liberally for me, you create true difficulties for me? The vortices from which we can see the suns touch upon the vortex where we are. The vortices are round, aren't they? And how can so many bubbles touch a single one? I'm trying to imagine but I feel that I can't."

"You show a lot of wit," I answered, "In having that difficulty, and even in being unable to solve it, because it's a good one in itself, and the manner in which you conceive of it. There's no response to it; and there's little wit in finding answers to something that has no answer. If our vortex is shaped like a die, it would have six flat faces and would be far from round, but on each of these faces you could put a vortex of the same size. If, instead of six flat faces, it has twenty, fifty, or even a thousand, we could have up to a thousand vortices that are posed on it, each on one of the faces, and you can imagine that a body has flat faces on its outside, the closer it comes to being round. It’s a bit like a diamond that is cut in facets all around it: if these facets were very small, would it be as round as a pearl of the same size. The vortices are round in the same manner. They have an infinity of faces on their exterior, each of which can carry another vortex. These faces are highly unequal, at some places bigger, at others, smaller. The smallest of our vortex, for instance, corresponds to the Milky Way and supports all these small Worlds.

If two vortices that are resting on two neighboring faces leave a bit of void between them at the bottom, as must happen very frequently, Nature will immediately manage the terrain well, and will fill this void for you with one or two little vortices that will not inconvenience the others and still leave one, two, or a thousand Worlds more. Thus we can observe many more Worlds than our vortex has faces to support. I would bet that although these small Worlds were made only for being thrown into these nooks of the Universe that otherwise would have remained useless, either because they were unknown by the other Worlds that touched them, they’re nevertheless quite pleased with themselves. It's them, undoubtedly of whom we have discovered little suns with tiny moons that are of such prodigious quantities. Finally, all these vortices adjust to each other the best they can, in such a way that each turns around its sun without changing place, each one taking the manner of turning that is most convenient and easiest in its situation. They interlock like cogs in a watch, and mutually aid each other's movements. Even so, they also act against each other. Each World, as they say, is like a balloon that self-inflates and that will expand, if it was allowed to, but it is quickly pushed back by its neighboring Worlds, and so it returns to itself, after it will start again to inflate, and so on. They claim that the Fixed Stars don't send us this trembling light, and don't appear to twinkle, if not for their vortices that push forever against ours, and are pushed back eternally."

"I like those ideas a lot," said the Marquise. "I like balloons that inflate and deflate all the time, and these Worlds that are always battling it out. I especially love to see how this fight starts an exchange of light, which is assuredly the only type of commerce they can have."

"No, no," I continued, "It's not the only one! The neighboring Worlds sometimes pay us a visit, even quite magnificently so. They send us comets, which are always ornate—either adorned by a sparkling head of hair or a venerable beard, or a majestic tail."

"Ah, such emissaries!" she said, laughing, "We can do without them visiting, it only makes one frightened."

"They only frighten children, " I replied, "Because of their extraordinary equipment, but there are many children. Comets are only planets that belong to a nearby vortex. They have their movements near the edges, but this vortex is perhaps differently squeezed by those around it, more rounded at the top and flatter at the bottom, and it's at the bottom that it faces us. These planets have begun near the top of their circular movement, and they could not foresee that at the bottom the vortex would be missing, because it is squashed there. In order to continue their circular motion they necessarily would have to enter into another vortex, which I suppose is ours, and they cut off the ends. Also, they are always very highly positioned towards us, and they often pass by Saturn.[3] It's necessary that in our system, for reasons that have nothing to do with our present subject, that because Saturn reaches at the two extremities of our vortex, it has a large empty space, without planets. Our enemies fault us with the uselessness of this large space. Let them no longer worry about this, because we've found the use, it's the pied-a-terre of foreign planets that enter into our World."

"I see," she said, "We don't allow them to enter into the heart of our vortex and with our planets, we receive them like a Great Lord [Sultan of the Ottoman Empire] receives the ambassadors they send him. He does not bestow the honor on them to lodge in Constantinople but only in a suburb of the City."

"We still have this in common with the Ottomans," I continued, "They receive ambassadors without sending any back, and we don't send any of our planets to any neighboring Worlds."

"Judging by all these things," she answered, "We are quite proud. Meanwhile, I don't know quite yet what to think of all of this. These foreign planets have quite a menacing air to them with their tails and their beards, and perhaps they send them to us to insult us, instead of ours, which are not made in the same way, and it would not be so proper to fear them when they go to the other Worlds."

"Tails and beards," I replied, "Are only appearance. The foreign planets are nothing different from ours, but when they enter into our vortex, they take on a tail or beard because of a strong illumination they receive from the sun. This has not been quite adequately explained, but we are sure it is only a sort of illumination, we will find out more when we can."

"I'd like it much," she continued, "That our Saturn would go and take a tail or a beard in another vortex, and would spread fear over there with that terrifying accompaniment, and then he would go and settle down here with the other planets and resume his normal functions."

"It's better for him," I replied, "That he never leaves our vortex. I've told you about the shock that occurs in the place where two vortices push against each other. I believe that in such a situation a poor planet can be quite brutally agitated, and its inhabitants don't fare much better. We think of ourselves being unhappy when a comet appears to us, but it's the comet that is quite unhappy. "

"I don't believe for a moment," said the Marquise, "That she brings us all her inhabitants in good health. Nothing is so entertaining than to change vortex. We who will never leave ours are leading a rather boring life. If the inhabitants of a comet have enough wits to foresee the time of their passage into our World, those who have already made the voyage can announce to the others in advance what they will see. 'You'll soon discover a planet with a large ring around it,' they might say when talking about Saturn. 'You'll see another with four smaller ones that follow it.' Maybe there are even people who are destined to witness the moment they enter into our World, and who will cry out "New sun! New sun!" much like sailors who cry out, "Land-ahoy!"

"You should therefore no longer feel sorry," I told her, "For the inhabitants of a comet. I hope nevertheless that you will pity those who live in a vortex where the sun just went out, and who live in an eternal night."

"What?", She exclaimed, "Do suns go out?"

"Yes, without a doubt," I replied. "The ancients have seen in the heavens Fixed Stars that we no longer observe. These suns have lost their light, to the great desolation of everyone in the vortex for sure, and certain death on all the planets, because what can you do without the sun?"

"This idea is too catastrophic," she continued, "Is there no way to spare me?"

"I can tell you if you like," I said to her, "What very clever people say, that the Fixed Stars that have disappeared did not go out, but that they are suns that are only half, that is to say, of which one part is obscured and the other luminous. As they revolve, they sometimes present us with their bright side, and sometimes the dark side, and that's why we no longer see them now. I could take it upon myself to oblige you with that opinion, which is nicer than the other, but I cannot take it with regard to certain stars that have a regular time when they appear and disappear, since we can begin to perceive them, otherwise the half suns could not exist. But what to say about suns that disappear and don't come back in the time that they surely were able to rotate? You're too fair to want me to believe that these are half-suns.

Meanwhile, I'll make yet another effort on your behalf. Let's say these suns are not extinguished, but that they've only plunged into the immense depth of the sky, and we cannot see them anymore. In that case, the vortex must have followed the sun, and then everything in it will be fine. It's true that the great majority of the Fixed Stars don't have this movement further away from us, because then in other times they should approach each other, and we would see some bigger and some smaller, which doesn't happen. But let's now suppose that there are some tiny vortices which are lighter and more agile and which slip between each other, making certain tours, and at the end of this they return, while the majority of vortices remain immobile. But here's a strange misfortune: there are Fixed Stars which just showed themselves to us, that spend a lot of time doing nothing but appearing and disappearing, and then disappearing entirely, half-suns that reappear on regulated times. These suns that plunge into the sky only disappear once, and then don't reappear for a long time. Now you must make a decision, Madame, with courage! These stars either should be suns that become sufficiently obscure to become invisible to our eyes, and next relight, or in the end will go out completely."

"How can a sun become obscure and go out completely," The Marquise asked, "if it is by itself a source of light?"

"That's the easiest thing in the world, according to Descartes," I answered, "Our sun has spots. Whether they are foams or mists, or anything that please you, these spots can thicken, or cloud together, or hang together, and they will then form a crust around the sun which grows ever thicker--and goodbye, sun! We have already made a lucky escape, they say. The sun has been very pale for entire years, for example, in the year following the death of Caesar. That was the crust that was beginning to form, but the force of the sun broke and dissipated it, but it might have continued, and we would've been lost."

"You make me tremble," said the Marquise, "Now that I know the possible aftermath of the pallor of the sun I think that instead of looking every morning in the mirror whether I'm looking pale, I'll go instead to look at the sky to see if the sun is still himself."

"Ah! Madame," I replied, "Rest assured, it takes time to destroy a World."

"Come on," she said, "It only takes time?"

"I admit it," I continued, "All this enormous mass of matter that makes up the universe is in a perpetual motion, of which none of the parts is entirely exempt, and as soon as there is movement somewhere, don't doubt it, it must result in changes, either slow, or fast, but always with the time proportioned to the effect.

The ancients pleased themselves imagining that the celestial bodies by nature never changed, because they never saw them yet change. But did they have the leisure to make sure through experience? The ancients were young before us. If roses that only bloomed for a day wrote histories, and left memories to each other, the first would make the portrait of their gardener in a certain way, and in over fifteen thousand ages of roses, the others who also left a testimony to those who must follow them did not change a thing. They would tell them We've always seen the same gardener. We've only ever seen him. He's always been how he is. Surely, he can't die like we do. He alone never changes.

Is this line of reasoning by the roses sound? Nevertheless, it's sounder than the reasoning of the ancients about the celestial bodies, and even if there was no change in the heavens up until the present day, when they appeared to mark that the heavens would always endure without any change, I don't believe them yet; I am waiting for a longer experience. Should we establish our duration, which is only an instant, for the measure of another? That is to say: what has endured five thousand times as long as we have, does it have to endure forever? One doesn't become eternal so easily! Rather, something should have passed many human lives before it begins to give any sign of immortality."

"Really," said the Marquise, "I see the Worlds quite far away to be able to claim it. I will only not do them the honor of comparing them to this gardener who outlasts the roses; these Worlds aren't like roses which are born and die in a garden one after the other, since I expect that if the old stars disappear, new ones will appear. Their kind must repair itself."

"You should not worry their kind will perish," I answered. "Some will tell you that suns will approach us after they've long been lost to us from the depths of the sky. Others will tell you that they are suns that have come loose from the dark crust that enveloped them. I can easily believe all of this to be the case, but I also believe that the universe could have been made in such a way that it generates new suns from time to time. Why couldn't the matter that is suitable for making a sun, having been dispersed in several different places, be gathered together in a certain place, and then throw the foundations for a new World? I have much more reason to believe in these new productions, because they accord well with the high opinion I have about the works of Nature. Would she really only have the secret to let grass or plants die in a continuous revolution? I am more persuaded, as are you, that she applies this same secret to the Worlds, which will not cost her more to do so."

"In good faith," said the Marquise, "I presently find the Worlds, the heavens and the celestial bodies so much subject to change that it has as already occurred to me."

"Let's do even better," I replied, "let's not talk about it, since you've already arrived at the final vault of the Heavens. To tell you there are even more stars there, I would have to be more skilled than I am. Put more Worlds there, or don't, it's up to you. This is the proper Empire of the philosophers where great invincible countries can be, or not, if we don't want them. It suffices me to have brought your mind as far as your eyes will go."

"What!" She exclaimed, "I have the whole system of the universe in my head! I am a scholar!"

"Yes," I replied, "You are indeed a scholar, and you're free to believe nothing I told you, as soon as you feel like it. I only ask that you repay me for my efforts in this way: whenever you see the sun or the sky, or the stars, think about me!"

[1] A World is roughly what we now call an (extra)solar system. There were many different theories of how a sun was able to have the planets circle around it, and in what sort of medium this would happen. One such theory was René Descartes's vortex theory, which he explained in his book The World, Or Treatise on Light. He held that the universe is filled with vortices, circling bands of material particles, in which the planetary orbits and other celestial motions are embedded. Fontenelle was an enthusiastic proponent of Descartes's theory.

[2] This is a reference to Jean Racine’s play Phèdre (Phaedra) first performed in 1677. Racine was one of the great 17th century playwrights, so this reference of a scene from the play would have been familiar to Fontenelle’s audience.

[3] At this point, Neptune and Pluto had not yet been discovered.