Against bucket lists

This picture shows a line of climbers attempting to reach the summit of Mount Everest. It now resembles a line at a Disney attraction, except that you are cold, on your feet for many more hours and that you could die.** Being in the line is rough. People yell at less experienced climbers who lose their footing and don't get smoothly ahead. Better guard your oxygen bottles, or they will be stolen. After all, the oxygen is not calculated to last in such a huge traffic jam.

American climber Don Cash had to wait several hours for the descent because a traffic jam had formed below. He had been on his feet for 12 hours. He fainted from altitude sickness, then en route to his camp he fainted once more, and his sherpas, trained in CPR and other first aid techniques, were unable to revive him. Climbers who undertake the journey commonly see corpses along the way, which cannot be removed safely, some even serving as landmarks. Cash had quit his job as a software salesman age 55 to climb the tallest mountain on each continent. A friend remarked he was someone who “definitely lived life to the fullest.”

We tend to think of people who do extreme things such as climbing the tallest mountain on earth as living life to the fullest, chasing their dreams, shifting their own goalposts. But what if this is the goal of thousands of others? We tend to think that traveling could change us fundamentally, but as Agnes Callard has noted, there's little basis for this belief. It is not a harmless illusion, because the environmental and societal footprint of so many bucket list items (which seem to be identical for many people) are great. Barcelona as a city has become less livable, for instance, with skyrocketing rents, because so many foreigners want to see it. How many tourists are merely checking off a list? How many have read anything about Barcelona, or the local culture beforehand?

In our highly regimented lives, which are dictated by work, commutes, and childcare, the bucket list of travel can give you a sense of agency—I did it! I scaled the Mount Everest! But then again, we fall into a different sort of regimentation. In the case of Everest there are several companies offering comprehensive packages for your stay and climb. It seems like we're unable to escape this sameness in our lives, no matter how hard we try. Quit your day job as a software salesman to then do what many before you have done and climb all these mountains. In this “age of authenticity,” as Charles Taylor characterized the post-1960s expression of individuality and self-expression, how can we still be authentic if all our experiences come prepackaged?

I'm more sympathetic to bucket lists with goals such as “write a novel.” I know many people have this on their bucket list, and they've tried it multiple times with NaNoWriMo or other initiatives. Others have had a novel in progress for decades. I don't know if these novels will ever appear, but at the very least, the novel will be uniquely your work. Unlike the prepackaged experiences of a selfie at Mount Fuji, they are better suited to the goal of self-expression.

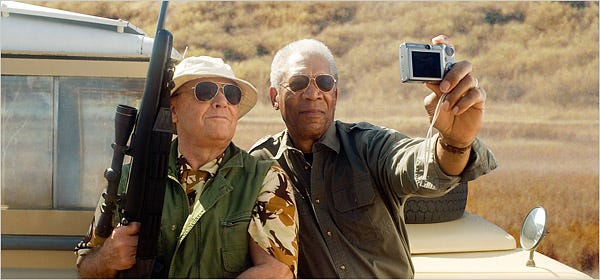

But overall, I'm not sure if they are ever useful. I discussed with a fellow cancer patient the idea of bucket lists, and I said (though it is also informed by the fact that I am quite physically disabled at the moment, it may be sour grapes…) “I just don't think I need bucket lists to prove that I've lived my life to the full.” He was wondering about it. It's intriguing that the film that popularized bucket lists, The Bucket List (2007) features two terminal cancer patients who travel to Rome, Egypt, India, and the Himalayas. So travel was an integral part of the bucket list experience from the onset, and bucket lists have contributed to mass tourism.

But what if, plausibly, living your life to the full doesn't require that you tick off checkmarks? There are already so many checkmarks that society (hetero- and middle class-dominated) wants you to tick off: have sex, have a long-term relationship, buy a house (hollow laughter), have children, a fulfilling career. Not meeting all these goals causes people anxiety, or they have to push back, as childfree people regularly have to defend their right to live a life without children.

If it is already so stressful to hit all the societal checkmarks, why should you then add some of your own? The idea might be that a bucket list can give you more focus to achieve the goals you want, but I'm not aware of any evidence that this would be so. Indeed, because you have to achieve the goals before you kick the proverbial bucket, one study, “The bucket list effect” finds that many people put off long-term goals of leisure and play to retirement. They follow a protestant work ethic whereby one delays gratification and then, once retired, they can finally play. What to do when that golden time comes? Oh wait, let's do what millions of others also have done. It sounds a bit miserable to me. For one thing, I'm a future discounter. At present, I have no idea if I will reach retirement age. I cannot afford to wait to live and do all grind first until I might reach whatever the retirement age would be. Fortunately, I decided against that sort of life in my mid-thirties and tried to always nurture my passions, such as sketching, playing music, reading also for pleasure, recently writing fiction.

Rather than bucket lists, I like Audre Lorde's notion of a fully realized self. She saw herself as many different ways of being: a mother, a lesbian, an activist, a poet, an essayist. This requires nurturing and not neglecting the different aspects of you. You don't need to wait until some future time when it is appropriate to finally enjoy gratification. I am also convinced that if people shifted more to this attitude, and societies would be set up to allow for it, our lives would be much richer, and places like Mount Everest would suffer far less severe pressure from over-tourism.

—

**This is not all year round but happens when weather conditions do not permit a climb for several days. It is still an indication of the mass tourism there.

I relate to this a lot as someone who has definitely not lived life to its fullest and has not even ticked most of the conventional societal checkmarks, let alone bucket-list ones. I love this reframing of expanding and deepening the range of ways in which to be one's self - being over doing. (Or maybe, fully being in whatever you're doing). I find myself wondering about someone like Kant, who never left his town and did more or less the same thing every day: would he have been happier if he forced himself to travel, have sex, branch out more? Maybe - but maybe he would have made himself miserable and stressed when it just wasn't for him.

The newest Wim Wenders film Perfect Days is about a middle-aged guy who does the same narrow range of things every day and hasn't realized any dreams ; he's not exactly happy, he's lonely, but you get the sense that his inner life is full and rich and maybe even his outer life, in its own way. Maybe this and Kant are bad examples, but for some reason they came to mind when I was reading your essay.

I really appreciate this take - a life well lived is one not defined by your random one-off experiences (climbing Everest), but by who you are and what you define yourself to be (a father, a husband, a writer, etc.)